A sideways look at economics

Trying to understand the world can often feel like you’re trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle but can only see two of the pieces at the same time. You stare at those two pieces alongside each other. If you think that they fit together then you put them to the side. If you don’t then you try again. The whole thing takes a long time and at the end of it all, you still only have a bunch of paired pieces rather than a completed puzzle. It would be a lot easier if you could look at more than two pieces at once, because then you could spot patterns and imagine how the pieces fit in the bigger picture. If you could see all the pieces face up on a table alongside each other, you might be able to make the obvious matches straight away and build whole chunks of the puzzle rather than just a bunch of pairs. (After starting with the corner pieces, obviously.)

In my job, I’m a data person. I like writing data processes and solving problems, so I’m well aware of the trap of zooming in; a trap that people in many other quantitative disciplines also need to be wary of. When you’re concentrating your hardest to solve a puzzle and you start getting caught up in the finer details, it becomes very easy to zoom in on those details to compare only two puzzle pieces. As soon as you do that and stop looking at the bigger picture, it becomes a lot harder to zoom out again.

Handling detail can be a real barrier to people coming to quantitative disciplines for the first time. It is easy to feel bombarded with terminology and detailed information, and to start believing that the subject is difficult to understand and is not accessible. But getting lost in the detail can equally be a barrier to people who are already comfortable with a discipline. Once you know a subject in more depth it’s even easier to get caught up in technicalities and lose your sense of perspective.

I believe this applies to everything in life, and not just work. Even people who are strictly rigorous in how they solve problems at work can often make irrational decisions when it comes to their own day-to-day lives. Most of the time this is only in little things, but it can affect big decisions too; the school we send our child to, how we vote, how well we look after our mental health – in all these situations, the quality of the choices we can make is affected by our ability to zoom out on a problem. It can have a huge impact on our lives.

The dangers of getting caught up in the detail are very real in science, too. As an example, take this piece of medical research in the cardiovascular section of the ‘Physicians’ Health Study’. The aim of the research was to gauge the effects of low-dose aspirin on cardiovascular health. There was a pretty reasonable sample size, with 22,071 participants. The study came up with some interesting results, suggesting that taking low-dose aspirin reduced the risk of heart attacks by 44%, although there was also some non-statistically significant evidence of an increase in risk of stroke.

The issue, however, was sample bias – the unreliability of conclusions that are drawn about the whole population based on evidence from only a certain type of person. In this case, the trouble was that the participants in the study were overwhelmingly male. This was highlighted in a follow up study that was published 16 years afterwards, which recruited 39,876 female participants. In this study, the effects of taking low-dose aspirin were found to be strikingly different for women. The researchers found no real effects on the risk of heart attacks. Conversely, they found it decreased the risk of strokes in women.

Ridker et al state that the initial 1989 paper “(demonstrates the results) … in men…There are few similar data in women.” In other words, as a result of a failure to zoom out and see the bigger picture when designing an important piece of research, inaccurate conclusions had been drawn and physicians had for over a decade been handing out erroneous health advice to half the population. Offering different advice to women at risk of heart attack or stroke during those 15 years could have had a significant impact on improving their health outcomes.

Sample bias is far from the only example of the problems that failing to zoom out and see the bigger picture can cause. Let’s look at an example of the spotlight effect, where people tend to have a disproportionate idea of how much attention is given to them by others. Imagine that you go into the bathroom at work and notice in the mirror that the middle button on your shirt has come open. (If you wouldn’t be embarrassed by this, then it’ll probably work better for this example if you pretend you’re less confident than you actually are!) You only spotted it when you were washing your hands and have no idea how long it has been open. If you zoom in on yourself and ignore the wider picture, your mind is prone to make an irrational leap — assuming the worst and imagining that everyone has been laughing at you behind your back.

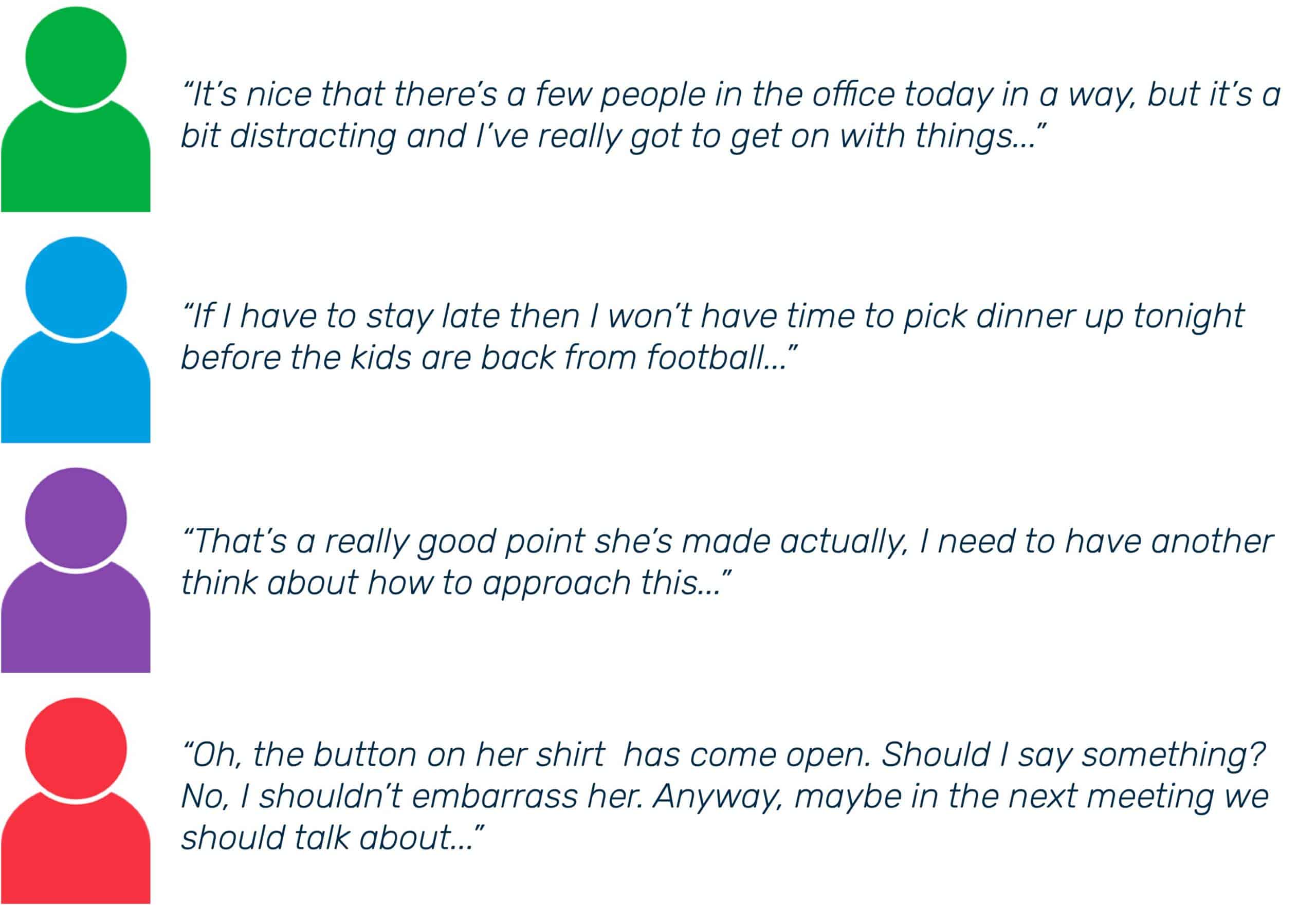

If, on the other hand, you zoom out of the situation, and start taking into account all the other things that your workmates are likely to be preoccupied by, you get a much more realistic and more forgiving picture. These are the sort of things that are much more likely to be going through their minds:

Seeing a situation as a whole rather than zooming in on your own feelings produces a view that is not only more balanced and more likely to be accurate, but is often more conducive to good mental health.

Obviously not every problem can be solved just by zooming out. If you never zoom in on a problem at all then there are a lot of things that you’ll never understand. But on the other hand, if you never zoom out on a problem, then you’ll never understand any of it.

Maybe it’s because we humans tend to focus on only the things we can see, but I find that when trying to solve a problem, widening my field of view is often a good place to start. It will always be difficult to piece together the information and form accurate conclusions when you haven’t got the whole picture.