A sideways look at economics

At 18:30 on Saturday 18 May 2019 the last scheduled High-Speed Train (HST) — familiar to those who remember the early marketing material as the InterCity 125 — left London Paddington for Exeter. It was the end of an era. This diesel locomotive, designed and built on a meagre budget by British Rail through the early 1970s, was never meant to last. It was intended as a stopgap measure before electrification could be rolled out across the UK’s long-distance rail network.[1] In the end, it gave more than 40 years of service on the mainline to Wales and the West Country, and it remains in use on other lines throughout the country. It was ahead of its time. The prototype reached 143 mph in 1973, setting a world record for diesel traction that the class still holds today. I have a personal attachment to the InterCity 125. As a child it would speed me away to my grandparents in the Midlands during school holidays. Then as I got older it would take me to Bath at the start of each university term.

Feeling a bit nostalgic as the service from Paddington came to an end, I scoured the internet for memorabilia, and found an old British Rail pamphlet, heralding the arrival of the new service. It’s reproduced above. The first thing that struck me was the journey times. London to Bath in 71 minutes? That seems quick even today. I checked, and it is. On the current timetable, the shortest journey time on that route, more than four decades later, is 83 minutes. And until recently, most services would take more than an hour and a half. So much for progress! Of course, it’s not only high-speed rail travel where we seem to have taken a step backwards. I still regret never having flown on Concorde. Introduced in 1976, the world’s first supersonic passenger aircraft was withdrawn in 2003, never to fly again.

It’s often suggested that the UK fails to invest enough, particularly in its transport network. But is that fair? As a share of its GDP, the UK currently invests less than any other G7 nation, and it has done so more or less continuously since at least 1980. But how much should we spend, and how much should we put away for a rainy day? As a nation, what proportion of our annual output should be consumed, and what proportion should be used to increase the capital stock? That’s one of the fundamental questions of economics, and at its heart there lies a very simple trade-off. The more we consume today, the greater the pleasure we experience in the here and now, or so the theory goes. But the less we consume today, and the more we invest in increasing our productive capacity, the more we can enjoy tomorrow. That suggests psychology might have a part to play in determining the optimal level of investment, and indeed it does.

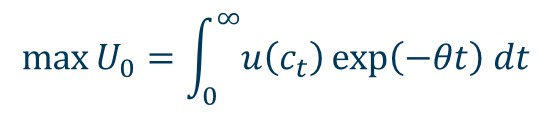

In his ‘A mathematical theory of saving’, Cambridge mathematician Frank Ramsey set out to derive a rule for the level of consumption that would maximise the present value of an individual’s expected future happiness.[2] Formally, he obtained a solution to the problem:

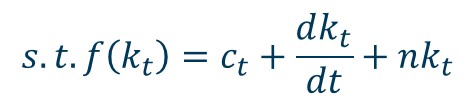

In the above, u(ct) is instantaneous utility (or ‘happiness’), which is assumed to be an increasing function of consumption per capita. It is then discounted at a rate θ to obtain the present value of expected future utility, U0. A benign central planner is then assumed to maximise U0 subject to the all-important constraint, representing the trade-off described above, which says that output (an increasing function of the capital stock per head, kt) is either invested, and used to raise the future capital stock, or it’s consumed.

The maths behind this problem is fiendishly complicated, to me at least, but a rather elegant solution emerges. It turns out that, when the economy is in long-run equilibrium, the following condition must hold:

Known as the Modified Golden Rule, this tells us that in long-run equilibrium the marginal product of capital should just equal the sum of the rate of growth of the population, n, and the discount rate, θ. Its elegance becomes apparent when we compare it with the much simpler Golden Rule:

The Golden Rule is a condition for the capital stock that maximises consumption per head. What Ramsey’s number crunching tells us, then, is that consumption per head will be less than its theoretical maximum by an amount that depends on impatience. The more rapidly one discounts the future, and the higher is θ, the higher must be the marginal product of capital. A higher marginal product of capital implies a lower capital stock, and a lower level of consumption per head.

Back to our original question. Is the UK really failing to invest enough? Possibly, but pointing out that the UK has a lower level of investment as a share of its GDP than any other G7 nation is certainly not proof positive. It may be that we Brits are relatively impatient, and that’s just part of the national psyche. There’s evidence of that elsewhere. Aside from our low levels of household saving, which aren’t unrelated to our low levels of investment, it’s also the case that we have fewer people in tertiary education than more or less any other G7 country.

Years of relatively low levels of investment, in both physical and intangible capital, have consequences. The output per hour of a UK worker is around 30% below US levels, and some 20% below levels seen Germany, and even France! Are we happy with that? If not, we need to change our mindset. We need to become more patient. Good things really do come to those who wait.

[1] Nearly half a century later, and we’re still waiting. Overhead line equipment is at last being installed on the Western mainline out of Paddington, but budget cuts mean that it will stop short of Bristol, while plans to electrify the Midland Mainline up to Sheffield have been scrapped.

[2] Frank Ramsey, ‘A mathematical theory of saving’, The Economic Journal, Vol. 38 (1928), pages 543-559.