A sideways look at economics

I recall, as a boy, lying in bed late in the morning, with the bright morning sunshine pouring in through the windows, warm, relaxed and perfectly comfortable. Dozing and waking, dreaming in that delicious state of being half-asleep and half-awake. Passing hours like that. Glorious hours. Occasionally my dad would yell from another room to enquire if I’d got up yet (my mum didn’t bother: she knew the answer). The day drifted away. Maybe I’d go out later, meet friends, kick a ball around.

Maybe not.

There would be many days like that, so no need to get stressed. Endless time, so it’s fine to waste it. Spend it like it’s nothing, like a millionaire.

Well, I’m now 59, and it’s not nothing anymore. Now, my time is full to bursting: today I had nine meetings (and I’m not done yet). When I carve out an hour that is not full, it’s like my precious only child: the focus of too much attention, too much anxiety. Hard to enjoy. And if I make time for friends (which I do all too rarely) there’s a part of me, that inner voice, saying: do you not realise how valuable your time is? And, while you’re choosing to regale me with another account of your bad knee, a little irritating voice balks, which I then silence with another inner-voice that says ‘be quiet’, ‘friends are worth it’, ‘this is worthwhile, it’s a good use of my valuable time’.

You don’t need to tell me I’ve got the whole thing backwards. I know.

Spending time with friends is only worth doing if you’re not counting, if the time is of no account. It’s like buying a round: that culture only works if no-one is counting. The same applies to carving out an hour — the hour can only be enjoyed if it doesn’t matter in the least. But, I confess that I find it harder as I get older to hold time as being of no account. Take today as an example, it’s a gorgeous, crisp, blue-sky March day. A blue day in March in London is a wonderful thing and it’s our moral duty, as I feel it, to bear witness. At 59, I wonder how many more like this I will get to witness it. Picture the river, glinting in the sun, or imagine taking a stroll through the parks with their sharp green spring grass broken up by the budding trees. How many more, like that, for me? I will be working; then, at the end I will be restricted in my movements, probably. So, the window of blue-March days (which are infrequent at the best of times)… is perhaps thirty? There are maybe thirty more days like this that I will be able to enjoy.

How can that calculus not change the way I perceive each one? And yet, I know that if I pile my expectations on each of those thirty days, the joy will disappear from them as surely as if I had had to do a cost-benefit analysis every time I kicked a football as a boy. I know that the right way, the only way, is to live each day as though you are going to live forever. It’s increasingly hard to maintain that illusion.

At Fathom, we offer staff the opportunity to trade up to five days per year: they can choose to work up to an extra five days (for additional pay pro rata) or up to five days fewer (for less pay pro rata). On average across all staff, the choice comes out at zero – there are changes, some more, some fewer, but it seems as though we’ve got the average structure between work and leisure about right.

That calculus is irrelevant for me, though. Of course, I work for money among other things, but five days’ worth of extra money (or less money) for me would have absolutely no impact on my working patterns. My time is full because that’s what I choose. I’m trying to build something, with my colleagues, and if I have the mental energy to spare I will devote it to that project, money or no money. That means those blue March days tend to pass me by.

That pattern of choices is vexing for the economist in me. Keynes, in 1930, argued that by 2030 we would be working around 15 hours a week on average, thanks to technological advances that made human labour redundant so we could enjoy much more leisure time. I suppose I could work 15-hour weeks, but why would I when I get so much enjoyment from what I do? What could be more enjoyable than meaningful work with colleagues I like?

Even that doesn’t really get to it though. As a boy I really enjoyed those long hours dozing in the sun. At that time, I couldn’t really imagine anything more enjoyable (apart from the obvious, and let’s not go there). I’m just not the same anymore. The idea is nice but, in reality, I would feel uncomfortable, with a need to move and stretch. And I would get bored. For now I need to be around people, doing something hard and challenging together.

One story about AI (the most recent advance in Keynes’ projection of labour-displacing technology) is that it will cause people to make a different choice between work and leisure. If it provides a way for people to stop doing the most boring, repetitive parts of their jobs, perhaps they will choose to devote those hours to leisure instead. I think this idea falls at the first fence: to do that, you’d have to accept less money, for a start, though that would not move my choice. More importantly, the average level of enjoyment that you derive from each hour spent working has just increased, with the result that your appetite for working will tend to increase, not decrease. It would decrease if AI took the most interesting parts of our work, not the most boring parts.

Speaking for myself, I’m fortunate enough now to be able to delegate most of the boring stuff. The consequence is that I work harder than ever – it’s just that I wouldn’t call it ‘work’ if that is taken to mean something that you would usually trade for leisure. The question in future will be whether that choice will be available to me: will AI take not just the boring work, but all the work?

Evidence that we have collected (hot off the press, and you’ll only see it here) suggests that we have nothing to fear so far. Mentions of AI in job ads are on average positively related to the number of jobs advertised. The implication is that AI is, on the whole, complementary to human labour at present. That’s the average result, although there are some sectors (food preparation, cleaning and sanitation, education and instruction), where the correlation is negative, suggesting displacement. But mentions of ‘generative AI’ in job ads — the stuff that mimics human intelligence most closely — is net negatively correlated with the number of jobs advertised on average, with the bulk of that apparent displacement focused on information, design and documentation, industrial engineering and ‘project management’, which are typically high-skilled jobs.

Interestingly, generative AI appears to complement human roles in sales, even though the average effect is negative. Perhaps that’s because of the so-called ‘uncanny valley’. Speaking for myself, I don’t mind interacting with an AI that is clearly a machine and not pretending to be anything else. But, when I discover that the person I thought I was talking to is actually a machine, it’s strongly off-putting for me. I will usually hang up or exit the dialogue box immediately. I wonder if that’s where the complementarity with human sales roles is coming from.

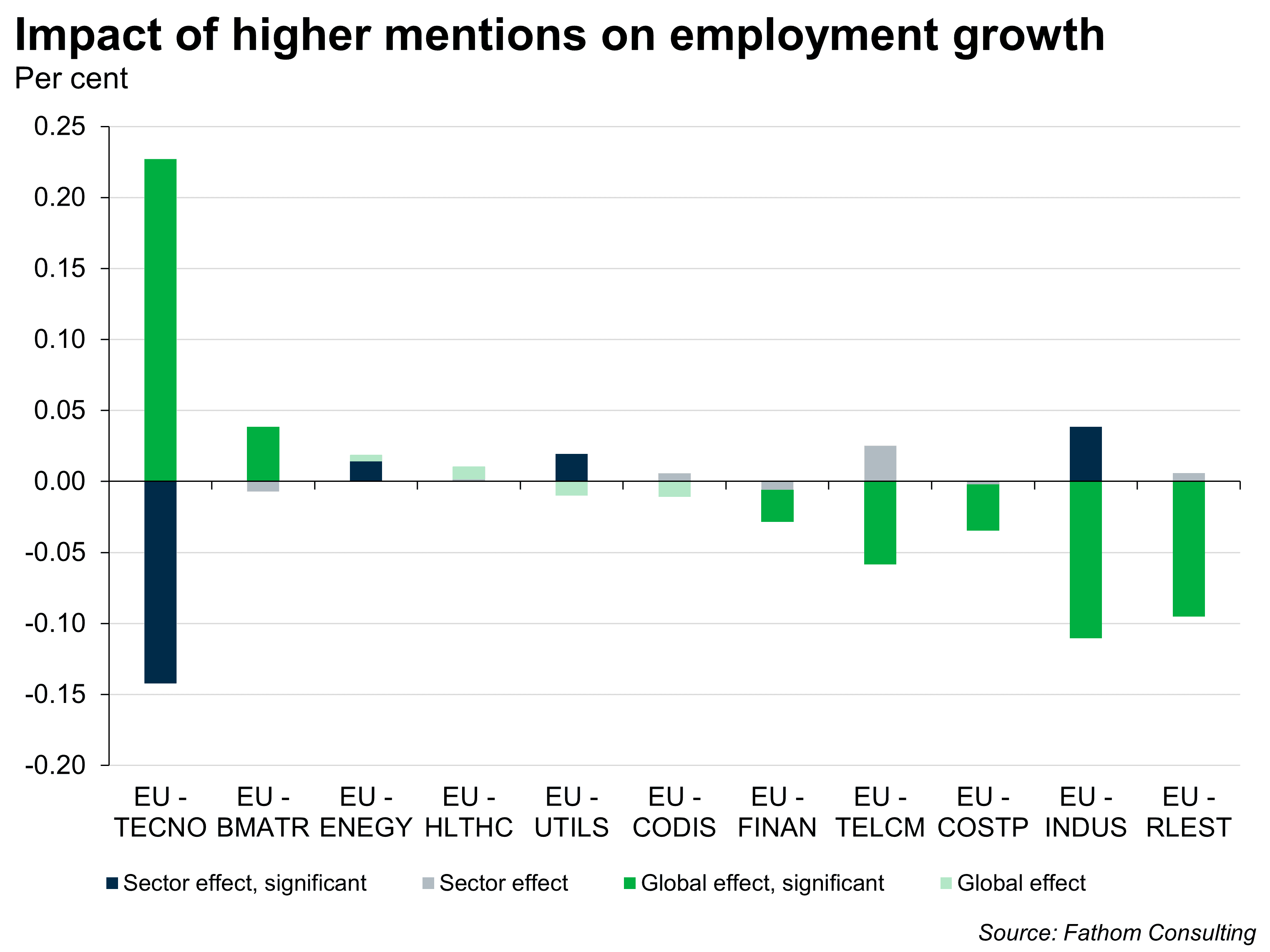

More than that, by analysing the transcripts of corporate earnings calls and correlating the mentions of AI with the growth in employment by the companies concerned, we can build the chart below. It turns out that if mentions of AI increase across all sectors, then the number of jobs in high-tech sectors tends to increase, while employment in more traditional industrial sectors or in service industries tends to decrease. When the whole economy is thinking about AI, they are intending to make more use of high-tech inputs (driving up the demand for labour in that sector) but to replace service inputs with AI (watch your backs, estate agents!). By contrast, when the tech sector increases its mentions of AI, employment within that sector tends to fall – whereas when traditional industry increases mentions of AI, employment in that sector tends to rise. Tech firms thinking about AI are intending to replace their employees with machines. Traditional industries are intending to enhance the productivity of their employees with machines.

Fathom is a service provider, suggesting that our clients might seek to replace our services with AI. That is definitely a theme we are facing. However, actually, the tasks we perform are probably not threatened by non-generative AI (in fact, more likely, they are complementary). It’s generative AI we should worry about, and then only if our clients can tolerate talking to a machine pretending to be me (who knows, perhaps they’d prefer it?). And an AGI (not on the horizon at present) would certainly create a challenge for my role.

If I have to go back to dozing and dreaming, I feel that I would regret the change. But maybe the boy I once was will come to the fore again in that world and wonder what on earth the whole blip in between was about.

More by this author

Intelligence is a property of systems