A sideways look at economics

‘An Englishman’s home is his castle’ is a rather tired expression, which I must admit I’ve never quite understood. Some suggest it describes a perceived right to do whatever one likes within one’s own four walls. If, however, it is intended to describe the majestic proportions of a typical home in this country, then nothing could be further from the truth. While working on a client project recently I came across an interesting article containing estimates of the average size of residential property across a disparate set of 24 countries. The smallest homes in the survey, with just 45m2 of floor space, were found in Hong Kong, and the largest, at 204m2, in Australia. This seems to make some sense. Hong Kong is very small and densely populated. Australia is very big and sparsely populated. Focusing on the 20 developed economies in the survey, the UK had the smallest homes, averaging 76m2. This will come as no surprise to those who live here.

How might we account for the dramatic variation in the size of homes across countries? Well, differences in land values almost certainly have something to do with it. When I studied economics in school, at the age of 16, we were told there were four factors of production: land, labour, capital, and ‘entrepreneurship’ – the one nobody could spell. Land and labour are (fairly) obvious. Capital in this case is simply the stock of tangible fixed capital, such as buildings, and plant and machinery. ‘Entrepreneurship’ is the art of combining the other three factors of production, ideally in new and interesting ways, to produce a flow of goods and services.

Why is all this relevant? Well, as I went further into the subject, beyond GCSE and A-level and on to my degree, land was quietly shelved from the analysis – it appears in few if any of the production functions that are used to provide a mathematical description of the production process. The amount of land is fixed, to a first approximation, while the amount of labour and the amount of capital can go up and down, which makes them more exciting. ‘Entrepreneurship’, sometimes referred to as ‘total factor productivity’, is the most worthy of attention because, although we can neither see nor measure it, it turns out that in an accounting sense it explains most of economic growth, particularly in the developed economies.

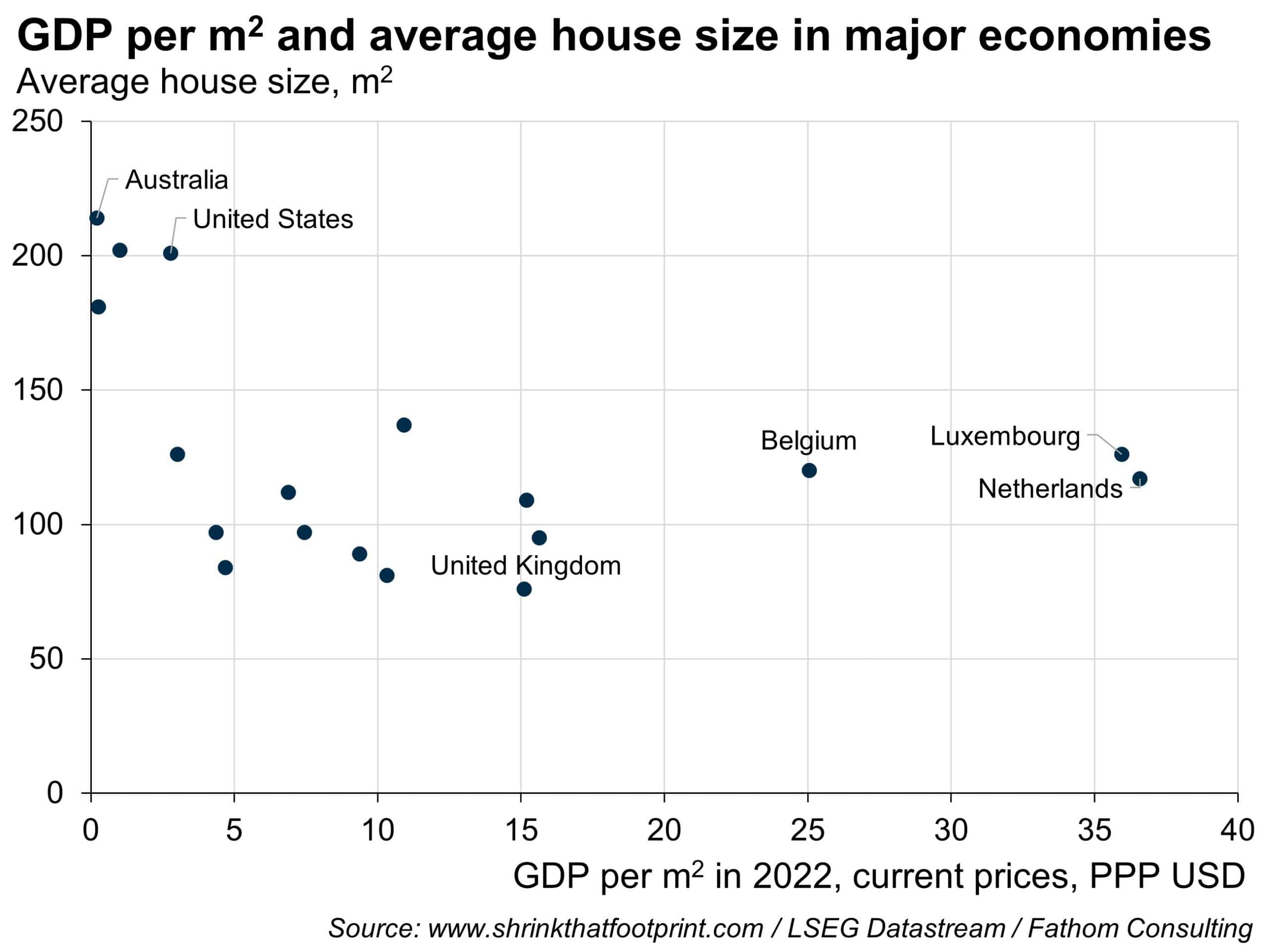

But back to land, the unloved factor. Just as one might measure labour productivity by looking at the amount produced per unit of labour, so too one might measure land productivity by looking at the amount produced per unit of land. This is a relevant concept because it measures the opportunity cost of using land for something other than direct production – such as living on it. I would expect countries where GDP per square metre of land is high to have more expensive and therefore smaller homes than countries where GDP per square metre of land is low.[1] And to a degree, my expectation is borne out by the data. The correlation between a country’s GDP per square metre and its average home size in my scatter plot below is -0.35.[2]

The land productivity data, or GDP per m2, are interesting in their own right. Of the 168 countries or land areas for which I could find comparable data, the most productive was Singapore, turning out a remarkable $1001.5 of GDP per square metre of land in 2022. Next most productive was Hong Kong, generating $483.1 of GDP per m2 in that same year. If we exclude city states and luxury island resorts – the Maldives were in fourth place – the country that was using its land most efficiently in 2022 turns out to have been the Netherlands, which produced $36.6 of GDP per m2. The UK was in 15th place, with $15.1 of GDP per m2 to its name, one place behind Germany, on $15.2, but ahead of France on $6.9.

This may be food for thought for those who argue that our tiny island is stretched to capacity. If we were to use our land as effectively as the Dutch, we might be able to generate more than twice as much output as we do currently. “Ah, but we have hills and mountains,” you may cry. Well, the Swiss are not known for the simplicity of their terrain, and yet they still extract around 25% more from each m2 of land than we manage to do here in the UK.

While average home sizes vary considerably across the major economies, the amount we spend on our homes is remarkably similar, with an OECD study published in 2022 finding that, in the vast majority of member states, the median debt-servicing burden on a mortgaged property was 15% of disposable income, give or take a percentage point. Where does this leave us? If you are currently living in the UK and really want a bigger house, for no more money, then a potential solution would be to move to a country that produces less economic output per square metre, and where land has a lower opportunity cost. My analysis suggests there are plenty of options out there. Indeed, 97% of the countries in the world get less out of their land than we do. And yet, according to ONS migration figures, the proportion of UK citizens leaving these shores for a life elsewhere has averaged just 0.1% over the past five years. So maybe there is more to life than a large home.

[1] I am oversimplifying somewhat. Other factors will, of course, influence average home size, including GDP per capita. Countries with higher GDP per capita tend to have more developed banking systems, and these are often necessary to finance the purchase of larger homes. Moreover, not all land is created equal. Some types of land are more amenable to economic development than others, whether through geography or restrictive regulation; and so land productivity, or GDP per square metre, is only a very simple metric for assessing the extent to which a country’s land resources are being fully utilised.

[2] If we strip out the Benelux countries, which appear to have relatively large homes despite the high productivity of their land, the correlation doubles to -0.70.

More by this author