A sideways look at economics

We’ve all hit that afternoon slump, when the clock seems to slow down and every task feels like a mountain. It’s in these moments that the idea of taking a break starts to sound not just appealing but necessary. As work environments change, especially with remote working, finding the right balance in how we take breaks can help prevent these slumps, and it is key to maintaining our health and momentum. But how should we take breaks effectively?

Our attitudes, as a society, to taking breaks has changed significantly. While seen as a hindrance to maximising the output of labour during the Industrial Revolution, breaks are today recognised as essential not just for boosting output but more importantly for our mental health. Pioneers such as the Ford Motor Company proved that better rested (and better paid) workers were more productive workers, helping end the common practise of 12- to 16-hour days with just a single hour break. However, we have taken a step back recently, as developments such as the rise of remote work and the ‘always-on’ culture have impacted many of the natural rhythms and social cues of taking breaks at work: chats by the water cooler, coffee breaks or even finishing on time. One recent survey indicated that, over the course of an eight-hour day, staff are productive for less than three hours on average. Self-regulation has become far more important in structuring workdays and, as a result, tools such as the Pomodoro Technique have become increasingly popular.

The Pomodoro Technique involves working in focused intervals, typically 25 minutes long, followed by a 5-minute break. After four of these intervals, known as ‘Pomodoros’ you take a longer break of 15-30 minutes. This technique claims to allow a person to maintain high levels of focus for extended periods of time, but how does it hold up against testing? Analysis across multiple studies, over the past 20 years, found that micro breaks (defined as under 10 minutes) did have a statistically significant but modest positive effect on well-being (increasing vigour and reducing fatigue). Despite being unable to conclude that micro breaks meaningfully increase performance, the study did find that the longer the break the better the subsequent performance of participants was.

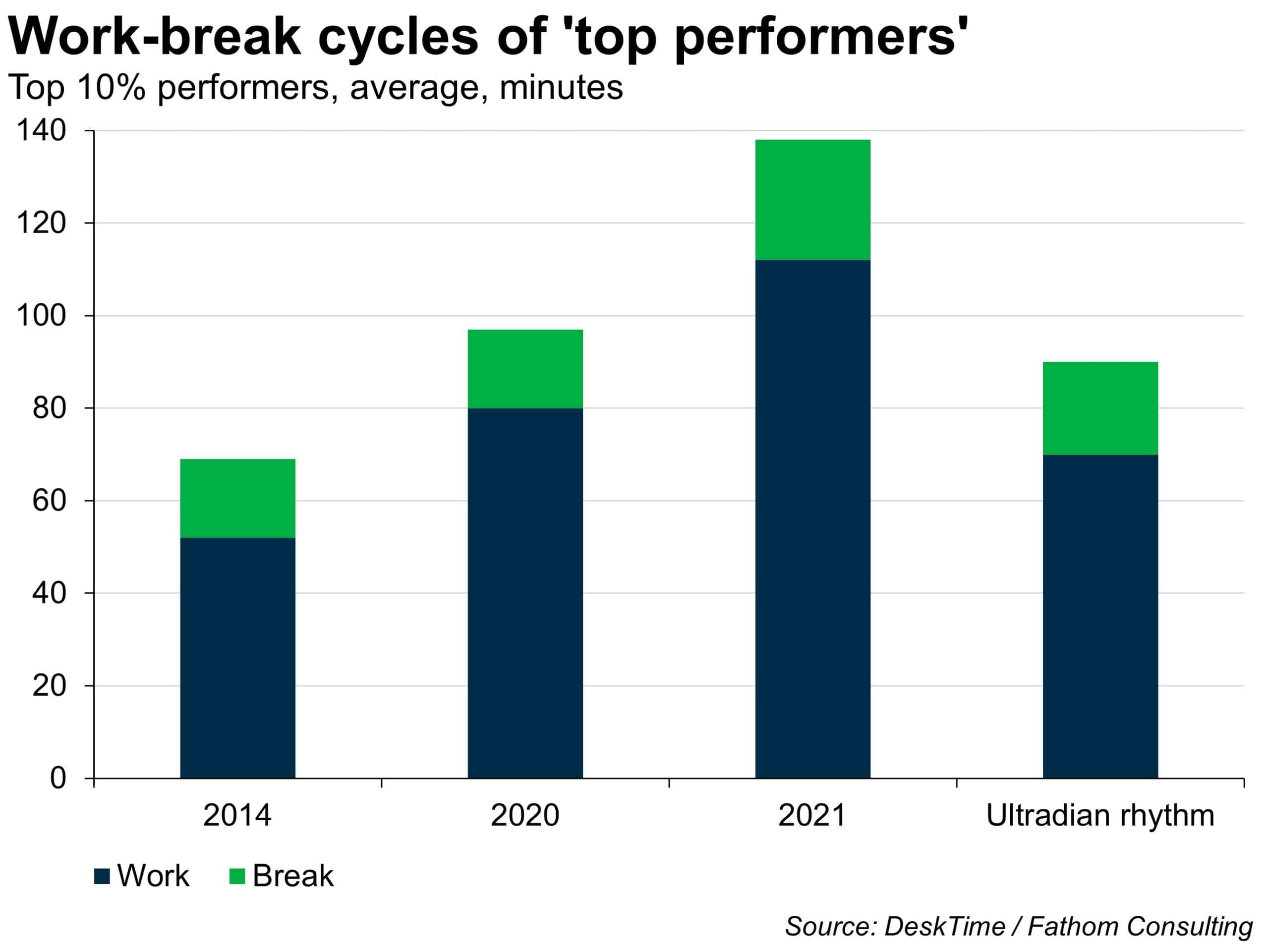

So, how do we use breaks to boost performance? A 2021 study by productivity app DeskTime found that their top 10% most productive users worked on average for 112 minutes followed by a 26 minute break. This ratio of work to break is up from a 2014 identical study, where the ratio was found to be 52/17, likely as a result of changing work habits from increased remote working. However, this analysis defined productive workers as those who had a ‘higher ratio of using productive applications’ rather than in terms of actual output and without consideration as to the sustainability. From this, it might be a stretch to conclude that this ratio is optimal for performance.

A more scientific approach, which encompasses our natural cycles, was undertaken by Nathaniel Kleitman, who is regarded as the father of modern sleep research. He analysed rest-activity cycles based on ‘ultradian rhythms’, natural cycles that occur typically every 90 minutes. Kleitman determined that both our bodies and minds experience peaks and troughs of energy and alertness within these cycles. By aligning work and rest periods with these rhythms — working for 70-minute intervals followed by 20 minutes of rest, for example, — individuals can in theory optimise productivity sustainably while minimising fatigue.

An interesting alternative perspective comes from research by Atsunori Ariga and Alejandro Lleras. They challenge the traditional view that breaks are effective through recharging your “attentional resources” and instead argue that they work by preventing the habituation, and therefore loss of focus, on your goal. Their study found that brief, mental breaks stop the brain adapting to the goal of the task and therefore required it to maintain focus. The results imply that when in a pinch and needing to focus for extended periods of time, short and well-timed pauses keep the mind engaged, thereby improving productivity during goal-oriented tasks.

Understanding the optimal frequency and duration of breaks is only half the picture, however. What activity we chose to do on our break is just as, if not more, important. A 2014 study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology explored the effectiveness of different types of activities during lunch breaks on employee recovery, well-being and subsequent work performance. The researchers compared relaxation activities (such as mindfulness exercises), social interactions, physical activities (like walking) and work-related tasks. The findings revealed that relaxation and physical activities were most effective at reducing stress and restoring energy levels, leading to improved mood and decreased fatigue. In contrast, work-related activities during breaks were the least effective, often leading to higher stress and fatigue. Social interactions had mixed results, with positive interactions boosting recovery, while work-related discussions during breaks were likely to have a negative effect.

So, while relaxing or doing physical activity seems to be the best type of break, the optimal timing depends on what task you’re doing. Rest-activity cycles of 70 minutes on and 20 minutes off, based around our ‘ultradian rhythms’, are better for more creative or cognitively demanding tasks. If you’re working on something more repetitive and on a shorter timescale, taking brief breaks has proved best as it stops your brain from adjusting and shifting into autopilot.

Yet, while we are aware of how the ideal break looks in theory, the reality of tight deadlines and demanding workloads often makes it challenging when trying to consistently apply these strategies. Ironically, the times when breaks will be most effective is precisely when we feel least able to take them. At Fathom we have an ethos that goes ‘when at our most stressed points, with large workloads and imminent deadlines, that is the time to take a long team lunch’. It’s a reminder that often, stepping back is the best way to move forward.