A sideways look at economics

Every time I speak about my job with family and friends back home, I always get the same comment: “Oh, so you are an economist? Then, what shares should I invest in?” Exhausted by consistently being faced with such a huge misunderstanding, today I have decided to write about what a professional economist actually does. Spoiler: you’ll be surprised!

Let me start by acknowledging that part of the blame lies with us economists, who for some reason have not been very good at explaining to society what we really do, and how important it is to have good economists. But a great element of responsibility must also lie with some of the media, for providing misleading information and calling some people ‘economists’ when they are not. The result of this is that — at least from my perception — the general public thinks that an economist is someone who buys and sells shares in the stock market, an accountant, or a guru who ‘predicts’ the next financial crisis using enigmatic techniques.

I am going to give you the first surprise: having studied economics does not make you an economist. And this is true for all the professions in the world: having studied law does not make you a lawyer, journalism a journalist, etc. The truth is that it is your actual job that defines your profession, not your academic background. But obviously, in order to practise that profession, you would need to have studied that particular subject. In other words, having studied economics is a necessary but not a sufficient condition to being an economist.[1] In this sense, economics is quite a particular case: although it is one of the most popular majors around the world, with millions of graduates every year, the number of people who actually decide to pursue a career as an economist is very low. I will come back later with the answer to why I think this happens.

So, what makes an economist from an academic point of view? You would need either a BSc, MSc or a PhD in economics, depending on which specific institution you would like to work for. There are also many cases in which the economist has studied something else for their bachelor’s degree (let’s say, mathematics or physics), but has then decided to switch to economics by pursuing a MSc or a PhD in the subject. One way or another, there is no way to become an economist without actually having studied it (and no, business administration or finance do not count!).

Having met that academic requirement, now we turn to the second and final condition, which is nothing more than having an economist’s job. This can be achieved by working in one of the following places:

- Academia: arguably the most important one, not only for economics but in all fields of knowledge. Academia is where knowledge is generated and science can advance. Academic economists work in universities, producing frontier research and giving classes. You would certainly need a PhD if you wanted to work here.

- International organisations: includes places such as the IMF, WTO, World Bank, etc. They do an essential job improving the standards of living of the global population, and I have the feeling that the general public doesn’t really understand how important they are. Economists in these kinds of institutions may find themselves designing a financial assistance package to help a country that is on the brink of default, or helping developing countries to design and implement structural reforms that result in lower poverty rates. Here too you would usually need a PhD, but there are some special cases in which a MSc plus relevant experience may be sufficient.

- Central banks: working here also means carrying out key tasks that affect the ordinary life of the citizens, as central banks control the quantity of money available in an economy, as well as supervising the stability of the financial system. The ideal background to be a central banker would be a PhD in economics, although again an MSc may be sufficient for some roles.

- Government institutions: again, key for improving welfare. Economists working in government institutions are in charge of designing and executing the economic policy agenda of governments. This may include drafting the budget, designing a tax reform, regulating the financial sector, or managing the issuance of government debt. There are also independent public bodies in charge of overseeing the government such as the Office for Budget Responsibility in the UK, of which I am a particular fan. In the UK a BSc or MSc might be enough to work here, whereas in my home country, Spain, you would also need to pass onerous civil service exams.[2]

- Financial sector: banks, insurance companies, hedge funds and asset managers employ many people with an economics degree, but most of them will not be employed as economists. An economist in the financial sector usually performs economic research and analysis to help decision-makers with different goals: for example, analysing country risks to help set thresholds for the degree of exposure that the institution can take, or designing plausible macroeconomic scenarios to support the institution’s stress-testing framework. There are also the so-called “macro strategists”, who do actually make investment recommendations — but always from a very broad (macro) perspective without focusing on particular stocks. Depending very much on where you work, the financial sector is one of the less restrictive places in terms of the academic background it requires.

- Economic consultancies: these apply economic analysis to solve complex problems for their clients. For example, Fathom Consulting provides general research at the intersection of macro, finance and geopolitics to a wide range of private- and public-sector clients, and also undertakes bespoke projects on specific issues. Fathom’s focus is on macroeconomics, but other consultancies may focus more on microeconomics (competition and regulatory policy, litigation etc.). The required academic background is quite flexible and depends on the institution.

- Others: there are also people working as an economist in places such as tech companies, think tanks and other private sector companies.

As you can see, an economics background opens the door to a wide range of interesting jobs. The problem is that these are usually not easy to get, as the amount of economist vacancies is much lower than for other types of roles. I suspect that this is probably why most economics students don’t go for it. However, if you’re really motivated to be an economist and follow the necessary steps, I have no doubt that you will end up making it.

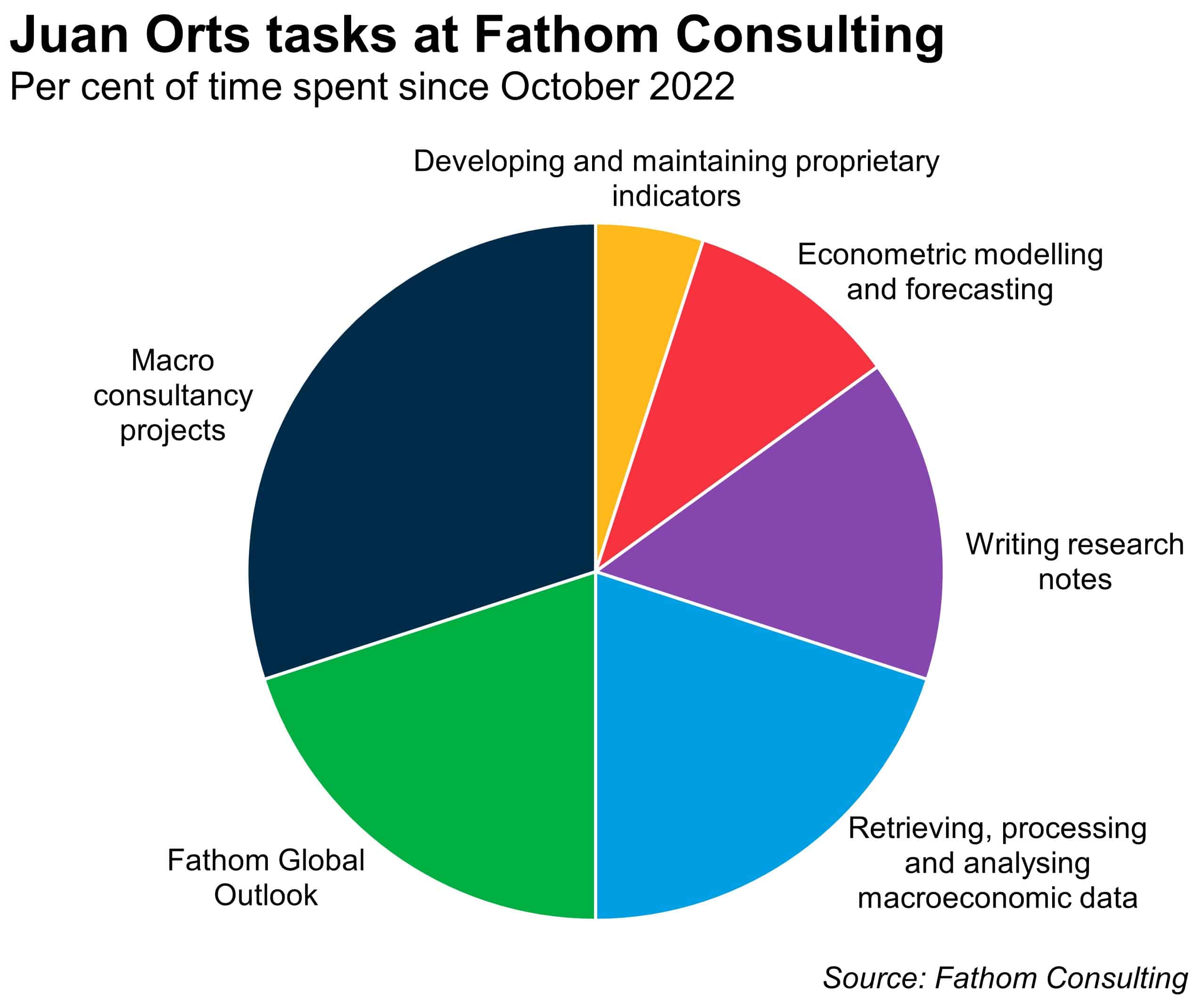

As you can see, an economist’s job has little to do with buying and selling shares or practising accounting. With regards to the final stereotype, that economists spend most of their time ‘predicting’ the future, a clarification is needed. Although forecasting is indeed one of the things that economists do, it is just one thing out of many. To give you an insightful example of what an economist may do in a place like Fathom Consulting, in the chart below you can find the different tasks that I have performed in my role since I started one year ago, and a very high-level approximation of how much time I have devoted to each of them.

I hope that this post has helped you gain a better idea of what economists do. But one final question remains: how do you find out if you want to become one? For anyone thinking about studying economics, I would particularly advise you to take the course if you prefer not to be pigeonholed in one particular subject, but rather enjoy a combination of the following to a certain degree: mathematics, history, economic geography, and philosophy. Economics is a multidisciplinary subject, and in my view that is what it makes it so appealing. Finally, for the economics graduates, I have a simpler piece of advice: come to Fathom and find out for yourself!

[1] This statement applies to a 21st century economist. In reality, economics as a degree was not introduced until well into the 19th century, and yet there were economists before that. A notable example is Adam Smith, considered the father of economics, who was a philosopher.

[2] For example, a position as a ‘State Economist’ in Spain requires several years of full-time study (10-12 hours per day) to pass the qualification exams, on top of a BSc. I am highly critical of this system, as only people with economic means can sustain themselves without a job for the study period, and it places a heavy mental health burden on the student that is completely unnecessary. Furthermore, the current syllabus is not well tailored to the skills that a modern economist needs.

More by this author

The inexorable fall of the suit