A sideways look at economics

What drives innovation? It’s almost a philosophical question with a variety of answers — far too many to dive into here. Some might say vision, experimentation, resilience, big companies with access to resources and talent, or even luck! I, for one, suggest productivity apps and ergonomic desk setups to help spark that innovative streak. However, to shed further light on this topic, I’ve chosen to take a look at one metric that could lead us towards a strictly financial value of innovation, by deep diving into startups — more specifically those elusive unicorns!

You might wonder what a mythical creature bursting out from a rainbow has to do with innovation. But, hear me out. In the business world they are almost real. Unicorn, a word coined by venture capitalist Aileen Lee, is a privately held startup that has soared to a valuation of $1 billion or more. And much like how people once accepted unicorns as real based on a little more than folklore despite the absence of hard evidence, modern markets often embrace startups as ‘unicorns’ swayed by the optimistic valuations and compelling narratives around them, without accurately pricing their profitability or risks. While their valuations might be debated, most modern unicorns do exhibit transformational power with the potential to disrupt existing business models and drive forward emerging trends like Artificial Intelligence, Fintech, or Space and Climate tech. And surely what better way to judge the unicorn landscape than by looking at the countries fostering their growth?

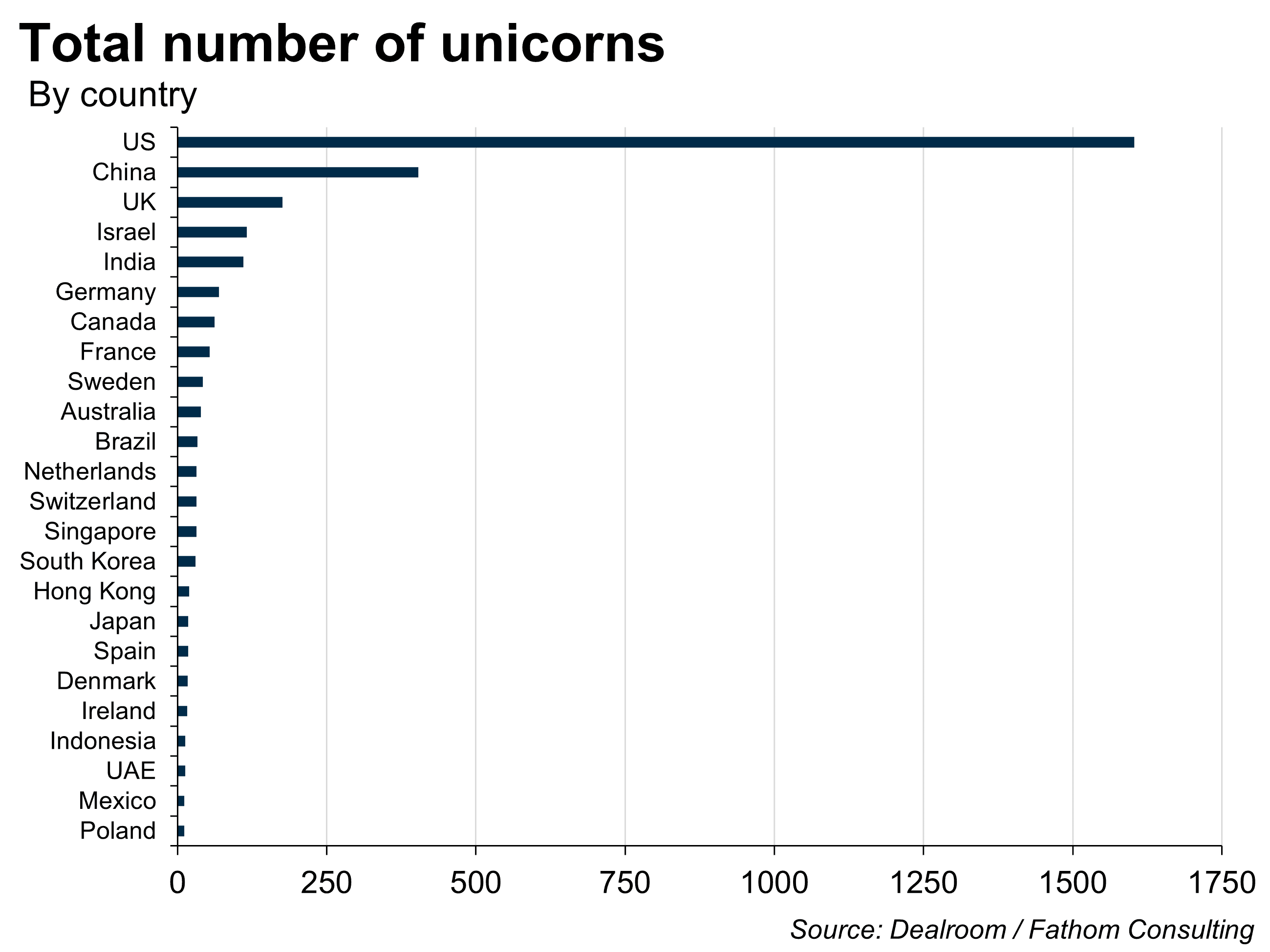

According to the rankings provided by Dealroom, the US leads the race by far, accounting for over 50% of the world’s billion-dollar startups. The Bay Area in San Francisco alone has produced around 25% of all unicorns globally, given its unique ecosystem of skilled talent, access to top-tier research institutions, experienced venture capital firms and a legacy of startups-turned-giants, like HP, Apple, Intel, Google and Facebook. It is followed by China, United Kingdom, Israel and India rounding up the top five.

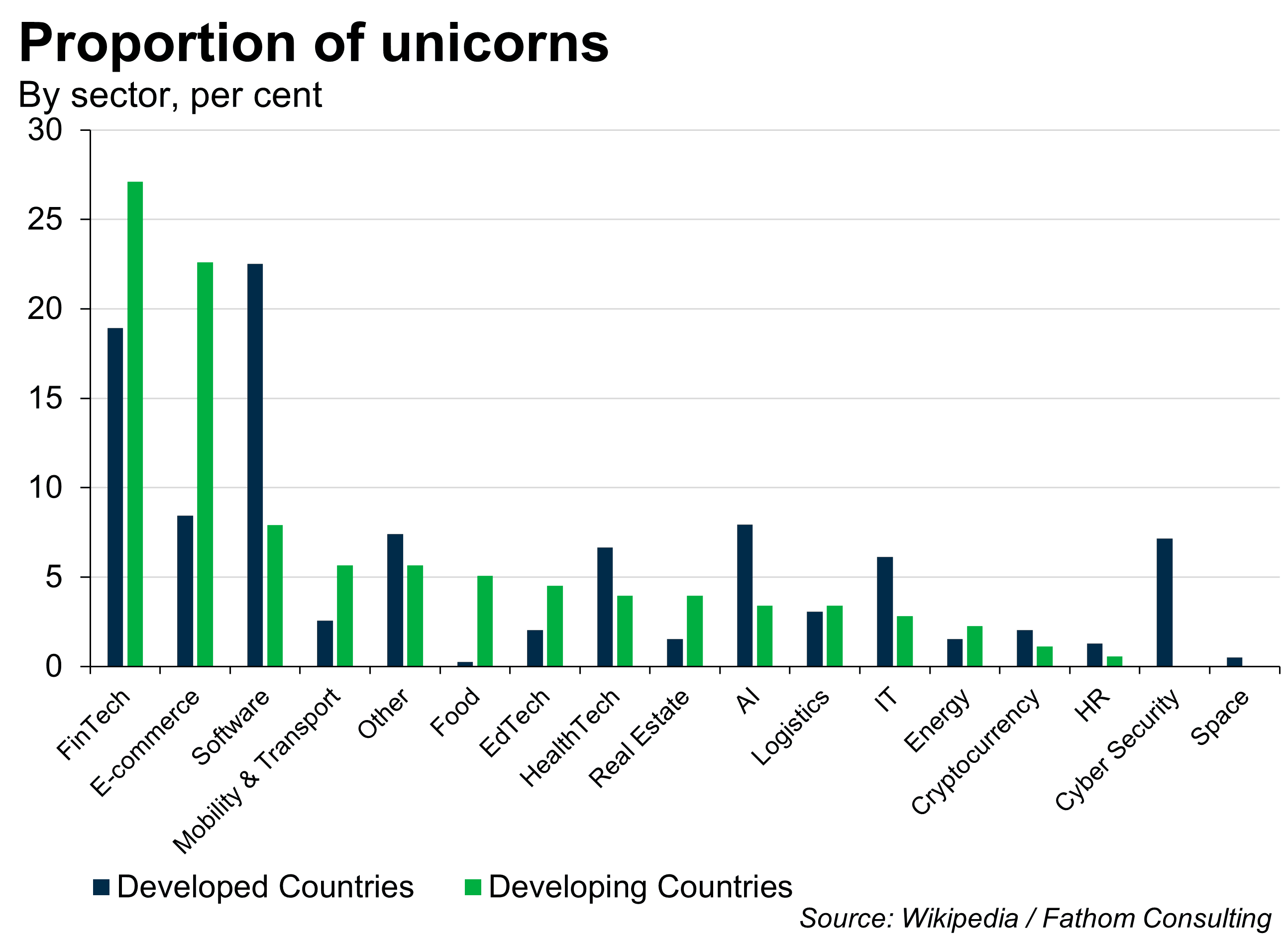

The countries at the top are all united by more common factors like high levels of GDP, large populations, favourable demographics etc., which makes it easier for startups to take off and scale up. It’s interesting to see emerging markets like China, India, Brazil and Indonesia ranking relatively high, even outpacing some more advanced economies. One potential reason is that startups in these countries are uniquely equipped to address the specific consumer needs of their sizeable middle class, like financial inclusion, access to affordable goods and services, urban congestion, etc., which might not exist in their developed counterparts. This fosters an environment where innovation is both necessary and profitable. It also explains why some of the biggest unicorns here are in sectors like Financial Technology (Fintech), E-Commerce, Software, Mobility & Transport, etc.

On the other hand, unicorns in advanced economies are typically oriented towards solving major global challenges or enhancing existing capabilities. Thus, unicorns here are largely in sectors that leverage cutting-edge technology, and serve both consumer and business markets, such as Software, FinTech, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Cyber Security, etc.

All of this can be broadly expected. Countries with a large population and high GDP would have a better chance of producing more unicorns than countries that don’t have the same demographics or access to capital. And, is distinguishing them based on their level of development really providing us with a true insight into which countries are genuinely innovating more than their peers?

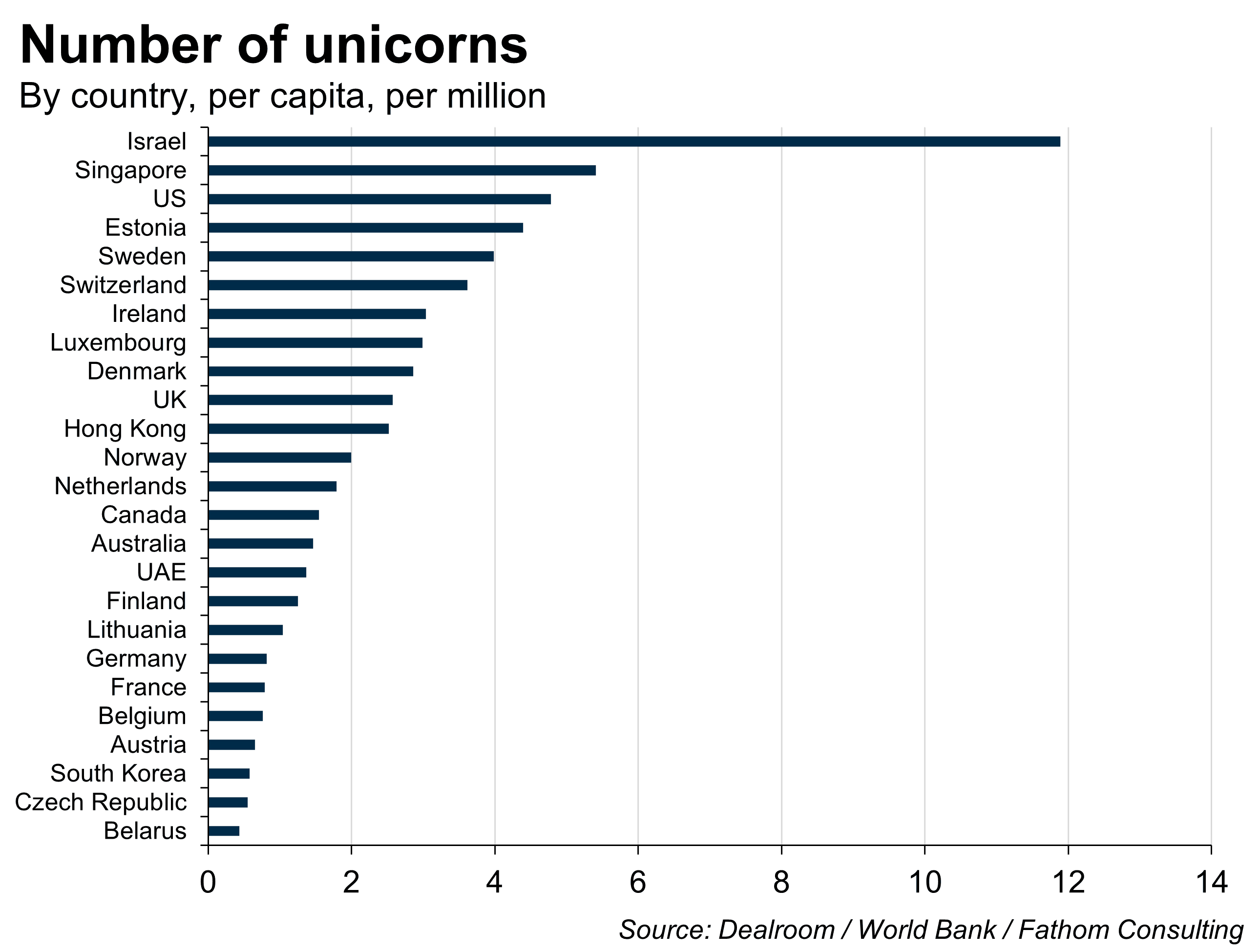

Unsatisfied with the above analysis, I took all this a step further and re-ranked the data by unicorns per capita (per million people) — and that led to things looking quite different.

With almost 12 unicorns for every one-million people, Israel moves to the top of the rankings, reflecting a vibrant startup ecosystem. Singapore, United States, Estonia and Sweden complete the top five. Notably, with a total population of just over a million people, Estonia is places significantly high — Estonian founders have launched some widely famous unicorns including Skype, Wise and Bolt.

This puts us in the dilemma of identifying what factors drive high rates of entrepreneurship in these countries. While each country has its unique attributes, I explored several possible common factors — including GDP, market size, access to capital and education levels, one striking factor that stuck out was the amount that the countries spend on research and development (R&D).

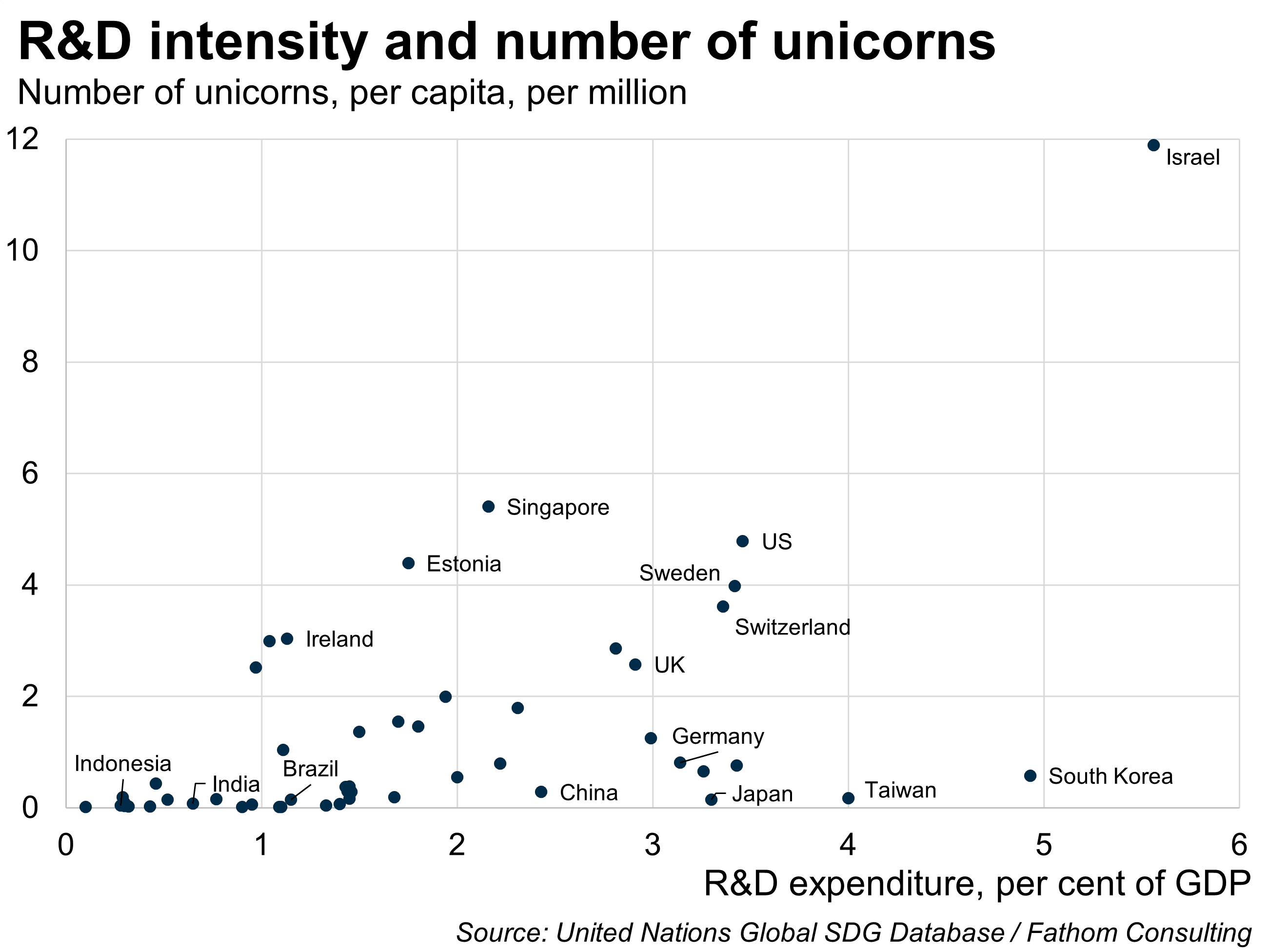

Mapping the expenditure of R&D against the number of unicorns reveals broadly three different pathways that countries take.

A linear path where higher R&D spending correlates with more unicorns per capita, which can be observed for developed western countries like the United States, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, for example. This finding aligns with the broader body of research on this subject. Global Innovation Index Reports (GII, 2020) highlighted that countries with higher R&D investments tend to see more startup activity, particularly in sectors like biotechnology, IT and advanced manufacturing.

Developed Asian countries like South Korea (with nearly 5% spend on R&D), Taiwan and Japan, as well as Germany, display a different pattern. Despite higher investment in R&D, they produce fewer than one unicorn per capita. These countries are home to major technology, electronics and automobile companies who mainly drive R&D investments rather than the government, which may leave less room for startups to flourish. With a median age of greater than 41 years, the ageing population in these countries could be another reason for low entrepreneurship. China’s position in this chart is also interesting to note. Although R&D spending accounts for 2.5% of its large GDP, the country produces less than one unicorn per capita, aligning more closely with the trends observed in other East Asian economies. However, unlike them, most of the private companies are linked to state enterprises, either through joint ventures or indirect equity connections, representing a form of ‘state-connected’ private ownership.

Israel stands out as an outlier given the disproportionately high number of unicorns for the R&D spending, which can be attributed to its unique startup ecosystem, fuelled by government programmes directed towards startups, and public funding supporting incubators and accelerators.[1] On the other hand, developing countries like Brazil, India, and Indonesia, with less R&D spending, generate less than one unicorn per capita. In developing nations, the focus on immediate socio-economic needs is often prioritised over fostering a culture of innovation and long-term investment in R&D, limiting the ability to cultivate a robust startup ecosystem.

The ideal position is the upper-left quadrant of the chart – Singapore, Estonia and Ireland displaying the best returns on R&D expenditure. These countries share traits beyond their compact size and coastal locations — like their prominence as global hubs for finance and tech, proximity to large markets, ranking highly in the global ‘ease of starting a business’ list, small and flexible governments all likely explain their innovation-driven economies.

Essentially, most countries can aim to emulate this path by creating a regulatory environment that encourages entrepreneurship through simplified bureaucracy, competitive tax regimes and protection of intellectual property. Additionally, a strong focus on digital infrastructure and access to capital markets alongside prioritising trade partnerships can open avenues for collaboration and investment, propelling home-grown startups into unicorns. It’s worth concluding that every country has its own unique circumstances and opportunities for driving innovation. Creating a unicorn is not an easy task, but by providing founders with a ripe environment for their ideas to take shape, countries can unlock their full potential and contribute meaningfully towards driving ‘new’ innovation.

[1] You can think of incubators as ‘nurseries’ for startups – they help startups in their early stages to develop their ideas into a real business. Accelerators are more like ‘bootcamps’ for startups, that take more developed startups and help them scale quickly.

More from Thank Fathom it’s Friday

How the giants came off the gold standard