A sideways look at economics

“This right to vote is the basic right without which all others are meaningless. It gives people, people as individuals, control over their own destinies.”

Lyndon B. Johnson

Political Britain is currently preoccupied by the question of who will be the next UK Prime Minister. Daily radio interviews and opinion pieces by the candidates, and even TV debates. It feels like we’re in the run-up to a general election. However, the next Prime Minister will not be chosen by the electorate, but solely by Conservative Party members. Maybe unsurprisingly, Tory members tend to come from a certain demographic group, meaning that the 65+ age group will have a disproportionate say in who will be the next Prime Minister.

The 65+ age group, a mixture of the generations usually labelled ‘Baby Boomers’ and the ‘Silent Generation’, is generally politically ‘overrepresented’. Almost 12 million people in the UK are 65 or older. More than double the number of 18-24-year-olds, a subset of the so-called ‘millennials’. Additionally, the 65+ group is more likely than other age cohorts to cast its vote at elections and referendums. For example, among the 65+ age group 90% of those registered to vote in the EU referendum did so, while among millennials less than two-thirds voted.[1] In the 2015 general election that difference between the 65+ and the 18-24 age groups amounted to 35 percentage points![2]

In Australia, voting is compulsory. Eligible Australian citizens must register and vote in federal elections, by-elections and referendums. What would Britain’s political landscape look like if it had the same rule?

In the recent elections for the European Parliament and in the 2017 general election the Labour Party performed better among young people while the Conservative Party had more support among the older generation. In the 2017 general election, fewer than one in five in the 70+ age group voted Labour. In contrast, Labour comfortably won more than 60% of the votes from the under-30s. The reverse is true for the Conservative Party. Indeed, only in the 50+ age group did the Conservatives win a higher share of the vote than Labour.

Due to the UK’s ‘first past the post’ system the impact compulsory voting would have had on the last general election outcome isn’t obvious. For example, London has a younger population than other parts of the UK. It’s also already ‘redder’ than the rest of the UK. A higher turnout of younger people registered in London constituencies would probably increase the total number of Labour votes relative to those of the Conservatives, but it might not increase the number of Labour MPs.

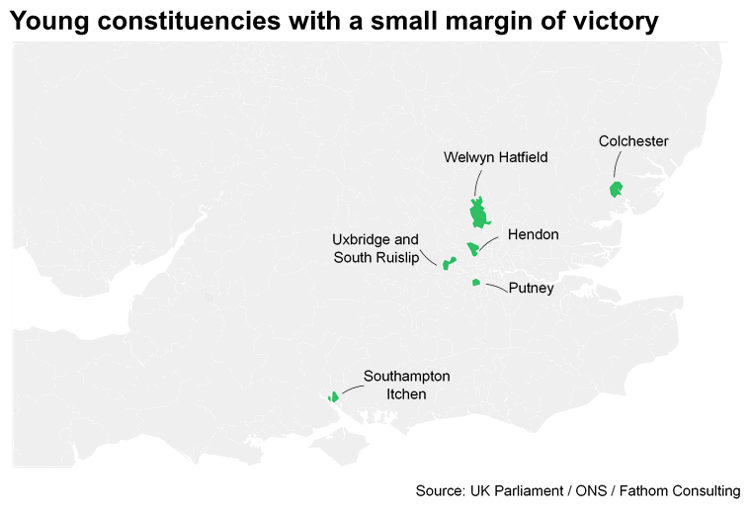

Compulsory voting would have the highest impact in young constituencies with a small margin of victory. The following chart shows the constituencies with a median age of 35 or below in which the Conservative Party’s share of the vote exceeded that of the Labour Party by 5 percentage points or less in the 2017 general election. These are the constituencies where a higher turnout among the young would make the greatest difference.

It’s easier to assess the impact compulsory voting would have had on the outcome of the EU referendum. Almost three-quarters of 18-24-year-olds voted ‘Remain’. This share gradually decreases for older age cohorts. Among those 65 or over, 60% voted ‘Leave’.[3] However, since younger people are less likely to vote, the UK voted to leave the EU by 51.9% to 48.1%.

If everybody eligible to vote had done so and assuming that those who didn’t vote would have voted identically to those in their age group who did vote [still with me?], the outcome of the referendum would have been reversed. ‘Remain’ would have won narrowly — 50.6% to 49.4%.

The past three years certainly would have been different.

Distributional economic outcomes might also be different if voting was compulsory or if the turnout among millennials was persistently higher. Politicians, of course, are aware that older people have a disproportional influence on electoral outcomes. Consequently, they might have an incentive to promote policies which appeal to these generations, perhaps in the form of targeted spending or tax cuts.

Only 15% of Conservative Party members support income redistribution. That is by far the lowest share among the major parties in the UK[4] and only half the share of UKIP members.[5]

And yet, intergenerational injustice has been rising and represents a major challenge of our time, according to the Resolution Foundation, which this week launched an Intergenerational Centre. Society is gloomy about the outlook of the young, too. Those pessimistic about young adults’ chances of improving on their parents’ lives outnumber optimists by two to one. This pessimism is most marked in relation to the key economic aspects of living standards — housing, work and pensions — where pessimists outnumber optimists by at least five to one.

This gloominess is well-founded. Again, according to the Resolution Foundation, “unexpected house price and pension windfalls have largely benefitted older cohorts with existing wealth, and are unlikely to be repeated in future.” Similarly, the UK’s ageing population is set to be a substantial burden on public finances going forward. The Resolution Foundation projects that borrowing to meet these costs would mean debt rising above 230% of GDP by the 2060s, passing the burden on to future generations who are already set to inherit higher debt levels following the financial crisis.

Pretty gloomy, indeed.

And yet, at least to some extent, the millennials hold it in their own hands to increase their political clout. Vote!

They might get a chance soon enough. As explained to clients as part of our latest quarterly Global Economic and Markets Outlook, we view a general election as the single most likely outcome of the Brexit impasse.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jul/09/young-people-referendum-turnout-brexit-twice-as-high

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2017-39965925

[3] https://lordashcroftpolls.com/2019/03/a-reminder-of-how-britain-voted-in-the-eu-referendum-and-why/

[4] The Brexit party isn’t part of this poll.

[5] According to research by Tim Bale of Queen Mary University of London and Paul Webb of the University of Sussex.