A sideways look at economics

“No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water.” H.G. Wells, War of the Worlds (1898)

Whenever I debate what to read next, I can’t help but recall the time I read The War of the Worlds — the writing style and vividness of Wells’ language still imprinted on me. That impression has lasted near-on a decade and has further spurred my interest to gradually venture onwards to explore other classic literature from authors long since passed.

I imagine it never crossed Wells’ or let alone the publisher’s minds that this story would last the test of time and possess such infamy, as it does. Indeed, the apparent fallout following Orson Welles’ radio broadcast adaptation for New Jersey in 1938 and film adaptations serve as testament. This got me thinking, how do you value an idea? Or even the impression someone leaves on you?

They can open doors — leading to chains of innovation that could improve the lives of millions, if not billions. Or they can serve to provide new ways of thinking and appreciation, driving a project or business forward.

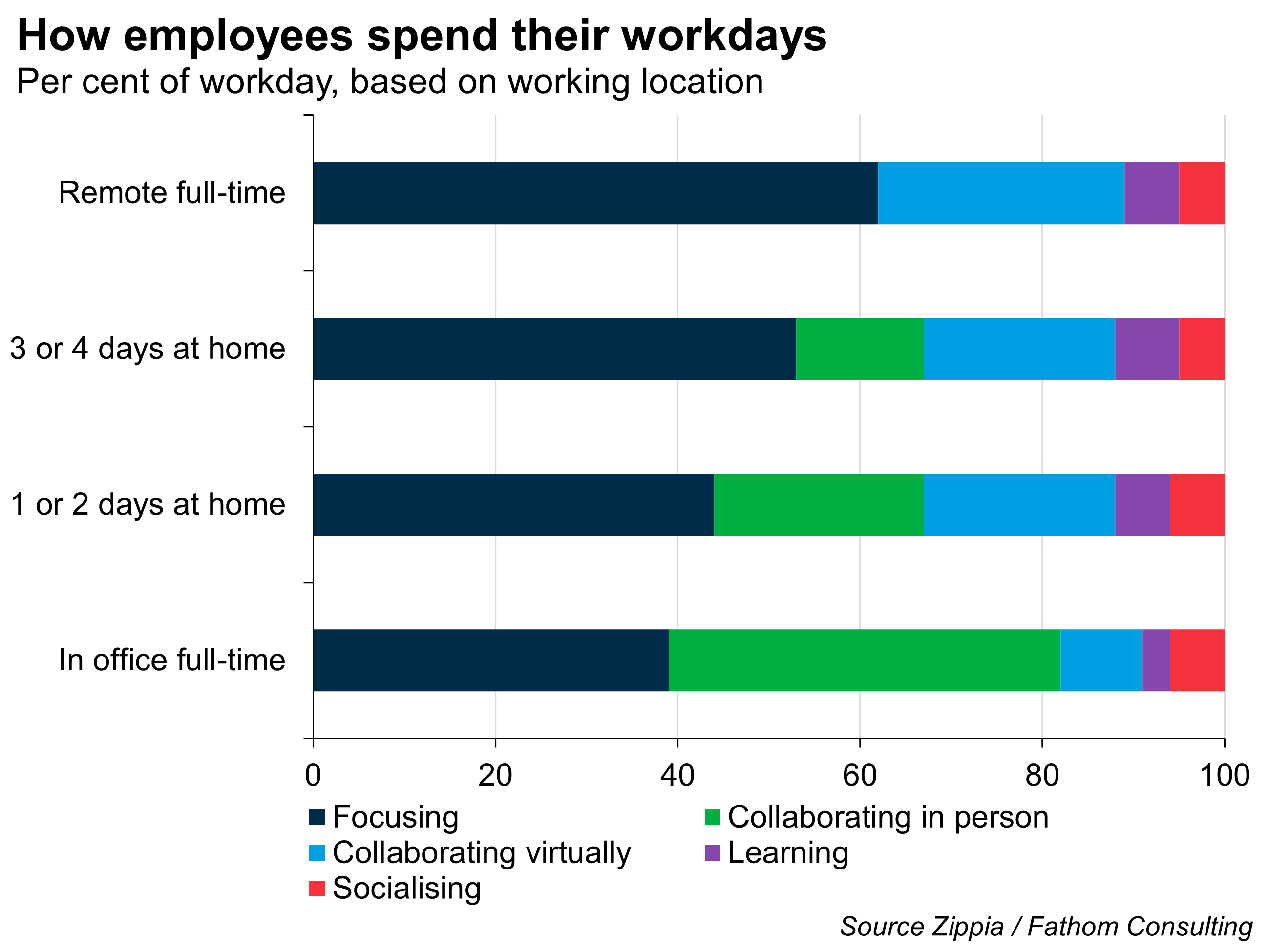

However, it is hard to necessarily know the true value of, or impact, that that idea may have — as famously noted with Vincent Van Gogh’s work — if it is not shared successfully. This could be one of the reasons why museum entry is free, due to the positive spillovers. More current, this may be a reason why more companies are ordering employees to return to the office on an almost, if not complete, full-time basis, with Zippia finding a positive relation between more time in the office and increased collaboration.

Yet, work from home appears sticky. Multiple workers are petitioning against their company’s return-to-office policy — despite this being a generally universal feature of employment five years ago, pre-pandemic. This is understandable, with individuals possibly having developed routines and livelihoods that are supported by remote or hybrid working. Or they are just savouring the days where they have more leisure time, as they are not required to commute and pay to go to work — while also absorbing some of the impact from the heightened cost of living.

Hence, something that appears quite simple could actually be quite complex, when having to weigh in happiness and consequently the motivation of workers. To what extent might a return to the office foster profitable ideas and boost company-wide success. Or, would individual productivity decrease with the chart suggesting workers spend more time ‘focused’ and ‘learning’ the less they are in the office. It is clear there will likely be a trade-off, but as workers adapted to working from home they can do the reverse too.

To me, this also represents an opportunity for an interesting social experiment to analyse preferences and see to what extent the pandemic has caused a permanent shift in the working environment — with some firms being remote working only. Simultaneously, this offers an opportunity to quantify the value of offices and personal communication, with a chance to analyse subsequent company performance. This may be from in-office scenarios, promoting greater company culture, idea creation and even inspiration from interactions with colleagues.

On a final note, next on my list of classics to inspire my creative thinking involves an amateur detective who resides at 221B Baker Street.

More from Thank Fathom it’s Friday

Pals, Pradas, PJs and the UK’s reluctance to get back to work