A sideways look at economics

Have you ever told a friend you loved their new haircut when, in reality, you didn’t? Or perhaps you’ve excused yourself from a social event by claiming you had a prior commitment? Let’s face it, we all tell the occasional fib. Lying, it seems, is an integral part of human interaction: in fact, research suggests we tell one or two lies on average a day. While some lies are harmless, others can have significant consequences, particularly in the realm of economics. Mazar, Ariely and Amir (2008) argue that dishonest actions can lose the US economy hundreds of millions of dollars annually in tax revenue, wages, investment, and hundreds of thousands of jobs.[1] For this reason, exploring the factors that drive dishonest behaviour is a key focus in behavioural economics.

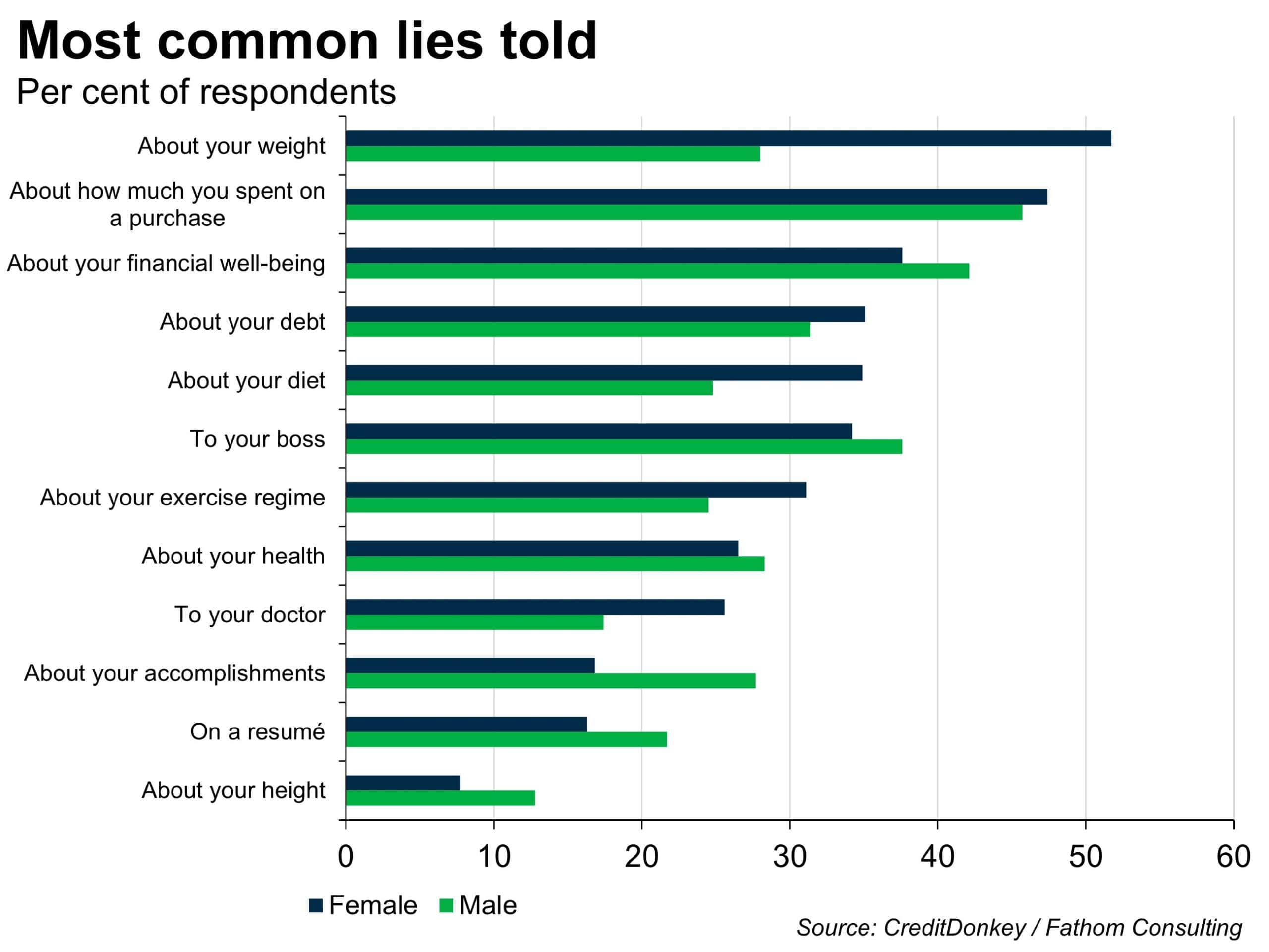

In everyday life, the most common lies told have been captured in a survey by CreditDonkey, a credit card comparison and financial education site. Their survey revealed interesting patterns in the types of lies people tell, as seen in the chart below.

Men are more likely to lie about money and achievements, while women tend to lie more about health and appearance. This difference might reflect the varying social pressures faced by men and women, but let’s not go into that today… The survey also highlighted who people lie to most often. It found that 43.6% of women admitted to bluffing their parents, compared to 37.4% of men. On the other hand, men are more likely to deceive their friends, with 44.1% compared to women’s 38.3%. Interestingly, both men and women are less likely to lie to their siblings or significant others. This might explain all the blackmail material I have on my brother! Of course, we must take these findings with a pinch of salt. After all, how can you trust a liar to be honest about their lies?

How we learn to lie

So when do we learn the behaviour of dishonesty? It turns out, lying is a sign of cognitive development in children. Around the age of two or three, children begin to lie as they realise they can influence the thoughts of others. This marks a significant milestone in their cognitive growth, demonstrating their emerging understanding of others’ perspectives.

Interestingly, the ability to lie well is linked to higher cognitive functions. Children who lie convincingly tend to have better executive functioning skills, which include problem-solving, planning, and impulse control. For parents and educators, understanding this can be crucial. Instead of punishing children harshly for lying, it can be more effective to guide them towards honesty by fostering an environment where they feel safe telling the truth. If only I’d heard this excuse sooner!

Gauging dishonesty

When it comes to understanding why people are dishonest, Dan Ariely, a behavioural economist, has some fascinating insights. In his Ted Talk, he discusses his experiments on cheating. Ariely concludes that cheating isn’t about a few bad apples; it’s a widespread behaviour, where many people cheat just a little bit. Traditional economic theory suggests that the decision to cheat boils down to a simple cost-benefit analysis. For example, if the expected monetary gains from lying in a tax return were to exceed the expected losses, Homo economicus would lie in his tax return and probably his insurance claims too. However, Ariely’s experiments show that people are often insensitive to these calculations. Instead, they cheat within what he calls a “personal fudge factor”, that allows them to maintain a positive self-image while still reaping some benefits.

One of Ariely’s most notable experiments involves a simple maths test. Participants were given a sheet with 20 basic maths problems, but not enough time to solve them all. When they had to submit their answers, the average score was four correct answers. However, when they were given the opportunity to destroy their answer sheets and simply report the number of problems they solved, the average jumped to seven. This showed that given the opportunity, people would cheat just a little bit, enough to gain but not so much that they felt like they were being dishonest.

This experiment highlighted a critical point: people cheat not because they are inherently bad, but because they can rationalise small acts of dishonesty. Ariely found that the extent of cheating didn’t increase with higher monetary rewards or lower chances of getting caught. People consistently cheated just a little, suggesting that the motivation to maintain a positive self-image was stronger than the lure of more money or the fear of being caught.

Ariely also discovered how being one step removed from the physical money impacted cheating. In another version of the experiment, instead of being paid in cash, participants were given tokens that they could exchange for money shortly after. This seemingly minor change led to a significant increase in cheating. Participants who were paid with tokens cheated twice as much as those paid directly in cash. This indicates that the further removed people are from the direct consequences of their actions (in this case, handling cash), the more likely they are to cheat. This insight could be applied to an individual’s response to climate change. People may be less likely to take action (and reduce their carbon footprint) for this cause rather than other equally worthwhile concerns because they feel detached from the consequences of their actions.

Economic impact

But while small acts of dishonesty may seem harmless, it is not to say that they cannot have large-scale economic consequences. A well known example, in economic theory, of how an individual’s dishonesty can have huge market consequences is Akerlof’s ‘Market for Lemons’ theory. Akerlof’s example involves the market for used cars, a buyer and a seller. There is asymmetric information between the two participants: the seller has more information than the buyer on the true condition of the car (e.g., whether it has been in an accident), and hence knows the true value. A ‘lemon’ is a car that is in poor condition, whereas a ‘peach’ is in good condition. Sellers have an incentive to lie about the true condition of their car to make a larger profit. Since buyers do not know whether they are buying a lemon or a peach, they are only willing to pay the average price of the two types of car. Peach sellers are undercut and eventually pushed out the market, leaving only the dodgy lemon sellers. Ultimately the market for used cars collapses, as buyers become increasingly wary of purchasing due to the prevalence of low-quality vehicles. This shows how an individual’s dishonest behaviour can in theory cause an entire market to fail.

So, we all lie, and we’re all lied to. I’m certainly guilty of claiming to be at a few more ‘family barbecues’ than I’m invited to. And while I’m sure my exaggerated schedule does not cause the market for pub trips in Reigate to collapse, dishonesty on a larger scale can have significant economic consequences. Understanding the motivations and impacts of dishonest behaviour is important, and it’s a growing topic of research in the field of behavioural economics. Ariely’s experiments and Akerlof’s theory show how dishonesty can erode entire markets, and it’s clear that small acts of deceit can aggregate into substantial issues. I guess honesty really is the best policy. But that being said, if I’m having a bad hair day, a little white lie wouldn’t hurt – would it?

[1] In their paper ‘The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance’ they give a few examples: the ‘tax gap’ between what people should pay versus what they actually pay exceeds $300 billion a year; the largest form of dishonesty comes from employee theft and fraud, which amounts to an approximate $600 billion annually.

More from Thank Fathom It’s Friday