A sideways look at economics

Owning and using a private jet has long been the status symbol of the elite in our society, from prominent celebrities to the most successful CEOs. Not many can deny that one of the primary reasons to fly a private jet is simply because they can. When I was asked to write a post for the famed Fathom blog, I gave a lot of thought to the topics that would best combine some of my interests. In the end, I decided a discussion around private jets and their place in our world today was the best way for me to talk about economics, climate change and planes all in one go. So, fasten your seatbelts!

When trying to justify to the shareholders the use of a corporate private jet, an argument that is often deployed is that the time savings more than make up for the cost. But is this true? Let’s break this down a bit more. A 2018 Willis Towers Watson study found that the average salary of the top 100 CEOs in Europe is approximately $6.56 million. Assuming they work 10 hours a day, for 335 days (about 11 months) a year, this would make their hourly salary $1958.

A brand-new private jet can cost anywhere between $2 million and $100 million – let’s make the pretty safe assumption of around $10 million. We must also account for the annual cost of maintaining an aircraft: around $500,000 at a minimum. Assuming that the private jet has a useful life of 30 years, a private jet would need to add around $833,000 in value every year to justify its purchase and use.

London to Paris is the most common private jet route in Europe and takes around 1 hour and 20 minutes to complete. If private jets allow three C-suite executives to ‘add value’ for the entire journey time and another hour on the ground, doing that journey by private jet has made the company $13,707. The cost of fuel, take-off and landing fees for this sort of journey comes up to around $1000, which is approximately the same cost as three business class tickets from London to Paris. So, let’s assume there are no additional cost savings on this front from using a private jet over a commercial flight. Note here that the counterfactual is that none of the three executives would have been able to be productive at all on a business class seat, whereas the private jet allows them to be fully productive. This may be an extreme assumption, but I am willing to concede it for the sake of the argument.

With these numbers in mind, a group of three C-Suite executives need to make around 61 such trips in a year to justify the use of a private jet. Note that if it is only one executive flying at a time this number will more than triple, since the cost per flight on a private jet will remain at $1000, whereas the alternative cost of a commercial flight will be a third of the value. Clearly, justifying the economic value of a private jet through time savings is a steep task. And even if one does believe that this number of flights is achievable for the jet-setting elites of today, there are other issues that call into question the economic viability of private jets. According to a study by the environmental advocacy group Transport and Environment, “a sizeable share of private flights are taken for private purposes (leisure and other) rather than business”. They find a clear peak of private aviation traffic in the summer months; this observation pours cold water on the idea that CEOs add value throughout the time they spend on a private jet.

So far, the discussion has stuck to the economic viability of planes for a given company, but in true economic fashion. To understand the actual impact of private jets, one must zoom out from private costs and consider the social costs of flying on a private jet compared to a commercial airliner.

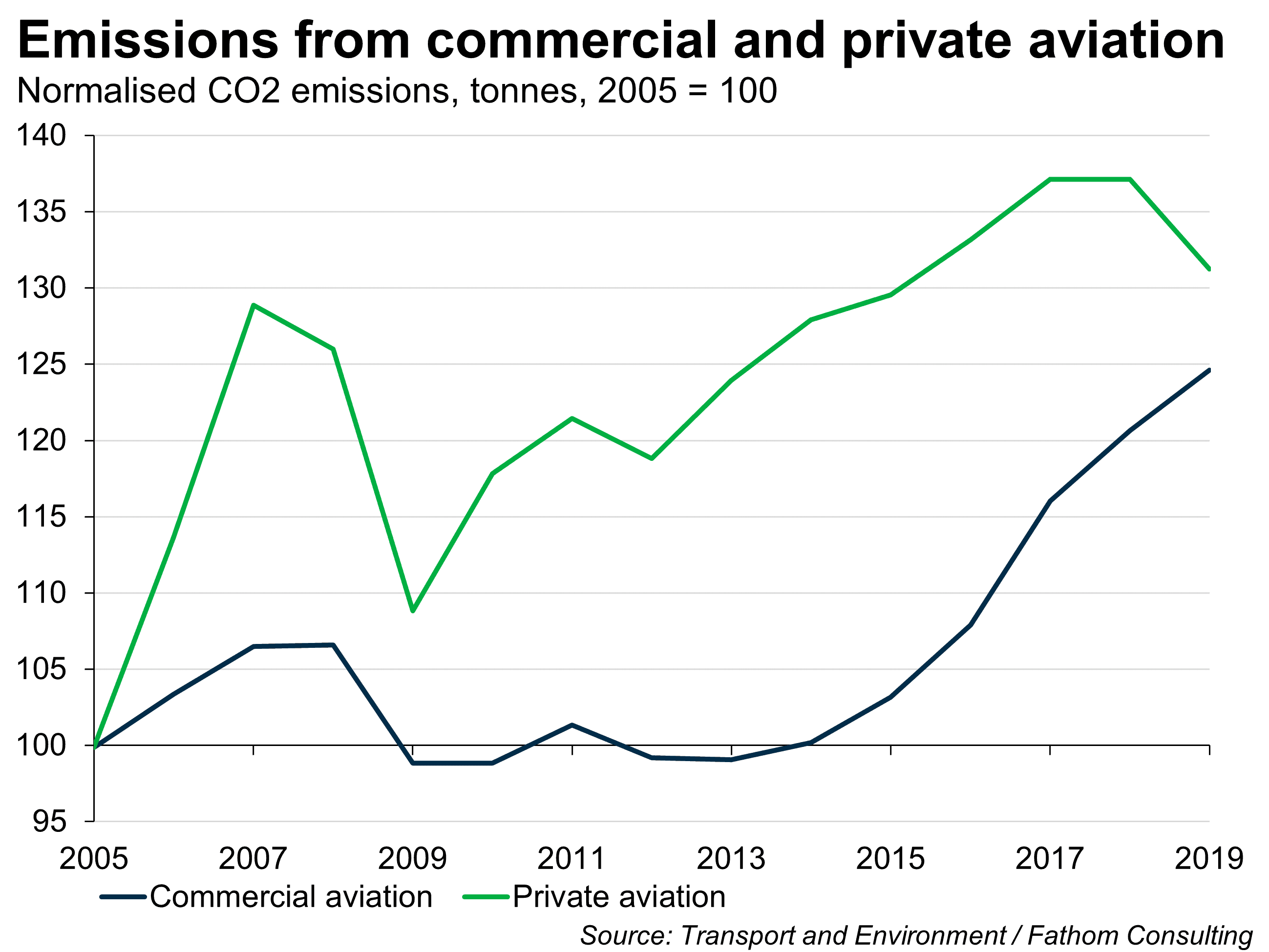

The same Transport and Environment study finds that private jets are on average 10 times more carbon intensive than commercial flights. The average commercial flight emits 128 grams of CO2 per passenger kilometer whereas a private jet emits 1300 grams of CO2 per passenger kilometer. The social cost of carbon, which is the cost to the world of emitting one more ton of carbon into the atmosphere, is estimated as $51 by the US government; the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) however has proposed a number as high as $190. Using the lower estimate, along with the knowledge that a flight from London to Paris is 343 kilometers, the additional cost to the society of someone using a private jet instead of a commercial plane to make one journey is $20. With more than 570,000 private jet flights registered in Europe in 2022, the annual social cost of private jet use over commercial flights would be around $11.4 million: a concerning number, when one considers that the share of aviation emissions from private flying has been on a long-term upward trajectory in recent years.

Aviation is recognised as a ‘hard-to-abate’ sector, and plenty of research and time has been spent on how to make the industry compatible with global net-zero ambitions. In that context, it is hard to ignore the $11.4 million dollars worth of annual damage that can be saved by simply trading a private flight in for a business-class ticket. If the CEOs do not wish to lose their private jets, then maybe policymakers can tax them for the additional social cost of carbon, and use these funds to support the research and development of electric- or hydrogen fuel cell-powered planes. The short-haul nature of most private jet flights makes them a top contender to be the first aviation sector to go fully net-zero too.

If this crude analysis has convinced you to ditch the idea of buying a private jet once you’ve saved up your next $10 million, I will feel vindicated. But whether the next-door private jet user is going to be convinced by the social cost of their decisions, I’m doubtful – because of course, every time we board a plane we are reminded to “wear your own oxygen masks before helping others”…

More from Thank Fathom It’s Friday

Cabin crew, ready for take-off