A sideways look at economics

I recently read in the news that US presidential candidate Kamala Harris is flirting with the idea of introducing a ban on ‘corporate price gouging’, in relation to food suppliers and grocery stores. As an economist, and the proud son of a father who has worked in the food business for more than thirty years, I could not resist writing a few lines to convince you that this plan is undoubtedly a rather bad idea. So, without further hesitation, let’s crack on!

Before I start, I want to clarify something rather important: this TFiF is not a statement of preference towards a certain candidate with orange vibes to win the next US elections (yes, I know you were just thinking about that). As a fiercely independent economist, it is my duty to defend or debunk economic policies regardless of who proposes them — no exceptions. This time Kamala is the lucky one, but any other politician is subject to my scrutiny, and I will have no mercy!

Jokes aside — I must admit that, at first glance, the idea of introducing a price ceiling (a maximum price at which a product can be sold in the market) on certain basic goods may sound very appealing to some. After all, and unless you are the devil incarnate, we would all like people to be able to put food on the table every day, so why not facilitate this by shielding them against price hikes? From how this sounds, it almost seems as though it is imperative to defend this policy if you want to call yourself a ‘good person’. However, us economists are trained to evaluate policies against their end result, rather than their intentions. And, it turns out, price controls, although well-intentioned, always[1] end up making things worse.

In this case specifically, the idea being floated around is to introduce a ban on so called ‘price-gouging’ by food suppliers and grocery stores in the US. This is a somewhat softer version of an outright price fixing policy and reports suggest that it would consist of preventing companies from raising prices only after some disruptive event that contracts supply or raises demand above normal levels has occurred. The claim that backs up this policy proposal is that, since pandemic times, food prices have been rising because a bunch of ‘greedy businessmen’ are exploiting consumers while running up excessive profits (I like to funnily caricature them as a group of overweight and suited up men, sitting in a fancy conference room while smoking cigars, laughing maliciously).

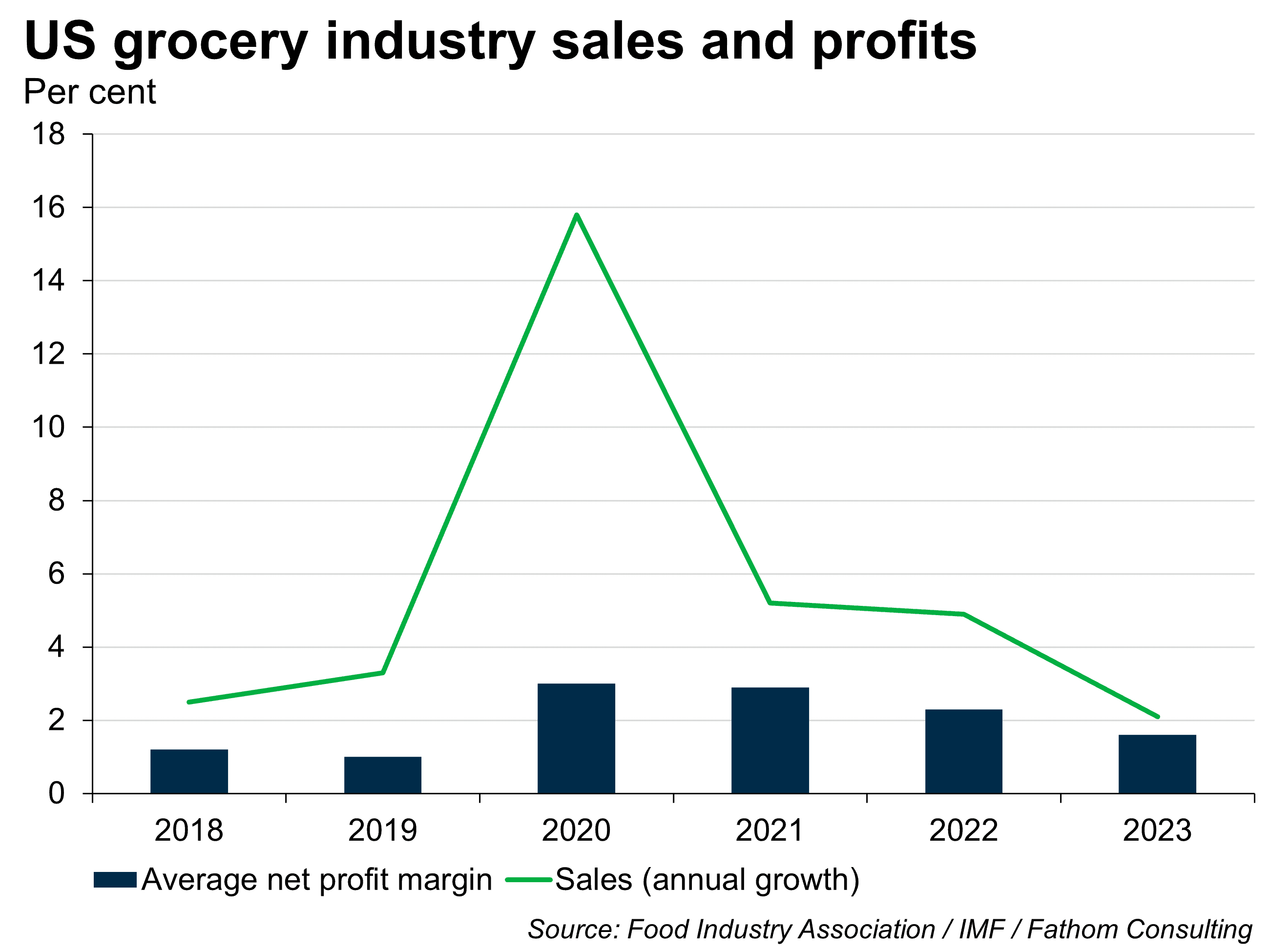

This claim is very far from reality, however. The grocery sector in the US (and I would argue that everywhere in advanced economies) behaves rather similarly to a perfectly competitive market: you have many buyers and sellers, substitutable products, no significant entry or exit barriers, and individuals behave as price-takers. In this environment, fierce competition between profit-maximising firms ensures that groceries arrive at cheap prices to consumer’s homes. And, if grocery prices increase that is probably because costs have risen too. Indeed, a recent study from the food industry association in collaboration with the IMF shows that, despite the significant increase in sales during the pandemic, grocery stores profit margins barely rose, with them now having fallen back to pre-pandemic levels.

When I showed this chart to my father, Juan (senior), who is in charge of our family business that has been running since 1896 (I invite you to take a look at their website, where you can peruse the amazing products we sell), he jumped from his chair and exclaimed: ‘Juan, believe it or not, but that is the same damn chart that we have at Harimsa!’. And then, he walked me through the story behind his response. It goes as follows: in 2020, sales rose sharply due to a temporary positive demand shock, stemming from the fact that people could not go out to restaurants and therefore had to eat at home — all of the time. In our particular case, we clearly benefitted from this situation, as people were bored during lockdown and tried making homemade pizza, cupcakes or any other flour-based product in their kitchens. As our costs remained the same during that period, our profit margins rose temporarily, but then they started to fall amidst the inflationary shock that ignited in 2021, while sales retreated as people resumed normality and started to go out to restaurants again. This trend was severely aggravated by the start of the war in Ukraine, when we (and the rest of the food sector) had to juggle to avoid experiencing losses due to skyrocketing costs (in our case, wheat prices, but also the rise in transportation costs, energy, etc.). Overall, and leaving aside any anecdotal evidence that I am sure exists, I believe that this chart clearly demonstrates how the food sector has not taken advantage of consumers.

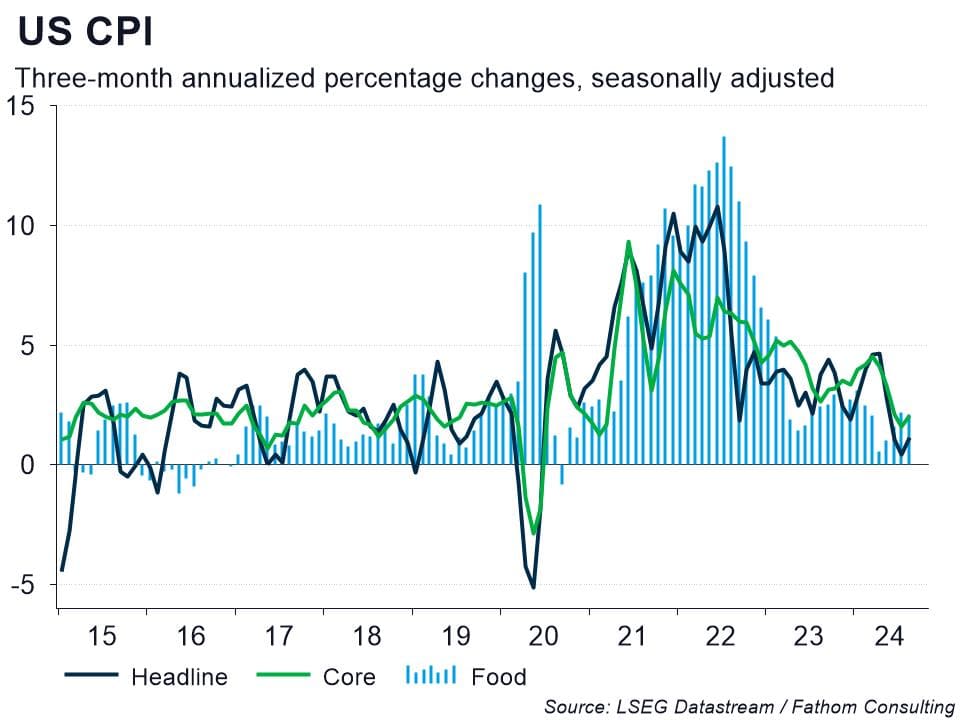

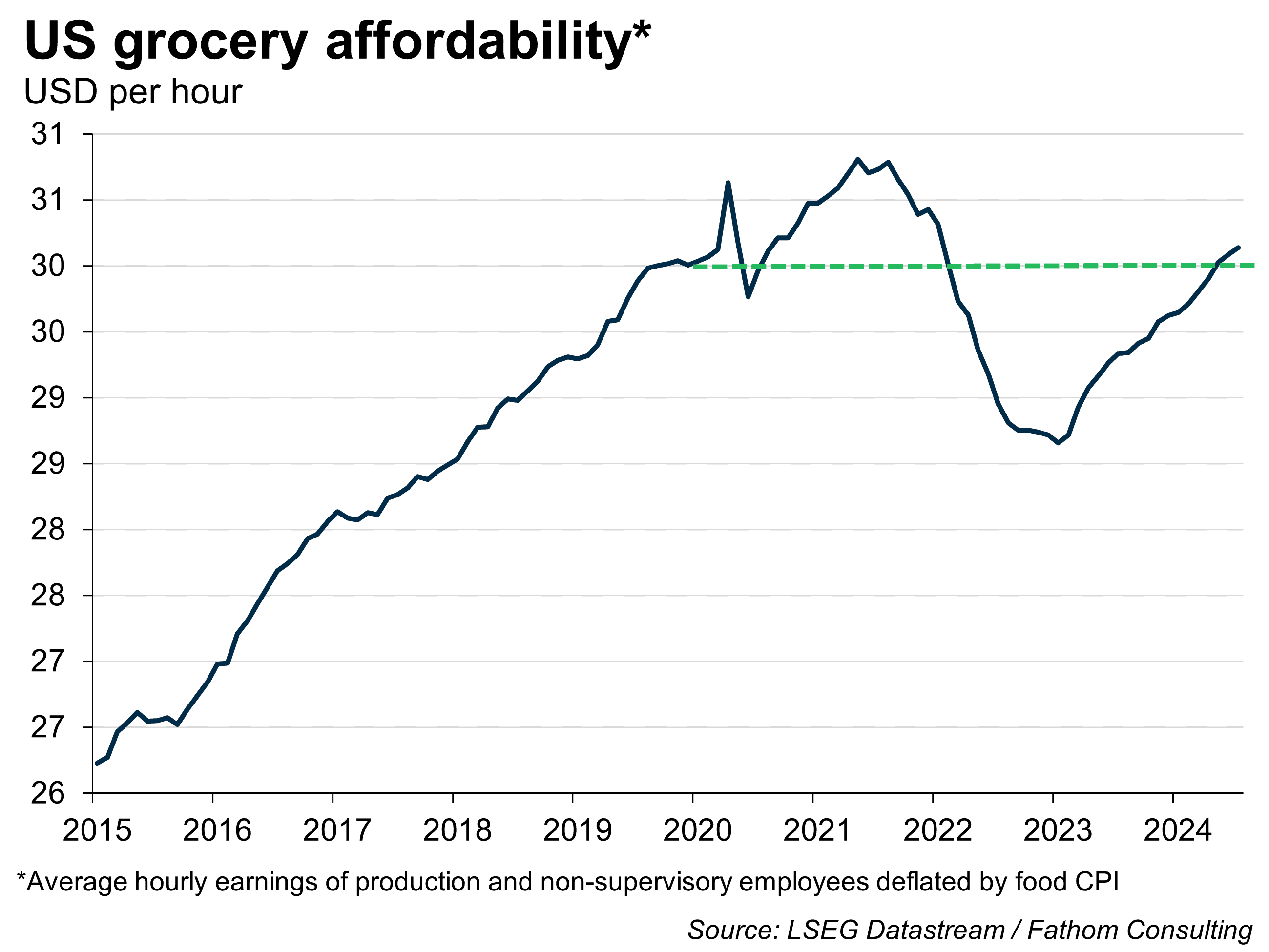

Not only is the main premise of this policy, which is vehemently defended, false, but the need to take urgent action on this matter doesn’t seem a necessity at the moment. As you can see in the chart below, US inflation is essentially back on target across the board. Of course this could change at some point in the future, but currently it is not an issue. To play devil’s advocate, one could (fairly) argue that what people care about is not so much the pace at which food prices are rising, but the price levels relative to pre-pandemic times. However, on this metric there also does not seem to be a problem: US consumers can afford more groceries now relative to 2019. While I understand that people are annoyed following the worst bout of inflation witnessed in decades — grocery affordability is more than 10% below its pre-pandemic trend — I do not think that the current situation calls for a dramatic policy fix.

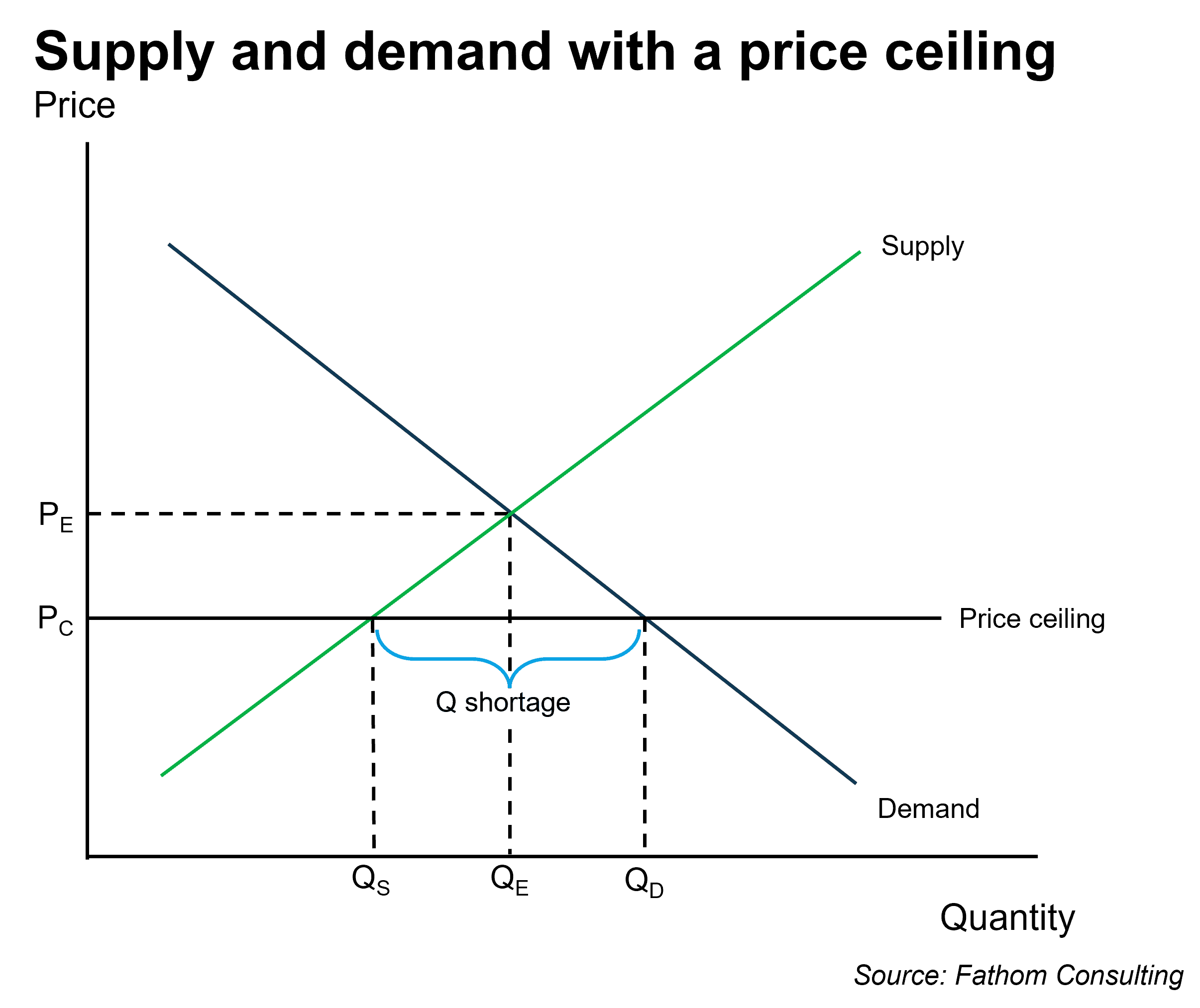

To wrap up my argument, I think it is illustrative to gauge the potential consequences of introducing food price controls through the lens of economic theory. On this occasion, the basic supply and demand model fits quite well for the question at hand, given the highly competitive nature of the food industry (so, sorry, but at this time I do not buy into the classic argument of ‘this model is not realistic’). The explanation of the chart below goes as follows: if a government prevents firms from raising prices in response to rising costs, what effectively happens is that they are then forcing these companies to sell at a loss. Since a firms’ goal is to minimise loss, the most likely consequence is that they will sell less quantity of the goods, potentially triggering shortages as supply is not enough to meet demand. Ultimately, higher prices allocate scarce goods to buyers who are most willing and able to pay for them, and this sends a signal to producers who can profit by increasing the quantity supplied. Price controls distort those signals, leading to a suboptimal outcome.

While shortages are a widely known consequence of price controls, there is a second consequence that usually garners less attention: inflation (yes, you read that correctly). While this only happens in extreme circumstances, price controls can lead to hoarding and the fostering of black markets, where prices rise steeply (even if this is not shown in official statistics). Furthermore, inflation can increase quickly once these controls are lifted. For example, some argue that the end of price controls was a big cause of the rapid rise of inflation in the US during the late 1970’s. However, it is important to be honest and highlight that the literature is not conclusive on this point. For example, Aparicio and Cavallo (2021)[2] found that Argentinian price controls during the period 2007-2015 only had a small and temporary effect on inflation, which dissipated quickly. Nevertheless, we could say that price controls are one of the (not many) topics that professional economists agree should be avoided[3]. Instead, we usually advocate for other type of policies to deal with a cost-of-living crisis, such as increasing government transfers towards lower-income households, or measures that can improve productivity, which results in higher wages.

Hopefully, this TFiF has achieved the goal of getting this idea of food price controls out of your head. Instead of doing the easy thing of blaming corporations in the grocery sector for what has happened, I think we should all do the opposite, and praise them for the hard and risky work they did during the pandemic, securing our food supply while most of us remained safe at home. Also, in addition to that, we should appreciate their continued efforts to deliver high quality and price competitive groceries to all of us.

Finally, I am going to dare to give you a small piece of advice: always be sceptical of economic policies that prompt ‘easy applause’, and be mindful of those that propose such ideas. While they certainly make their advocates look like kind-hearted, amazing people, who care so much about the poor, the reality is always a lot more complicated.

[1] This applies to price controls on competitive markets, such as the food market. Other special types of markets, such as regulated monopolies, may benefit from these policies.

[2] Diego Aparicio, Alberto Cavallo, ‘Targeted price controls on supermarket products’, 2021.

[3] A poll conducted by the University of Chicago asked renowned economists whether inflation was due to corporations taking advantage of their power to raise prices. 80% of them disagreed.

More from Thank Fathom It’s Friday

Labour market’s impossible trinity