A sideways look at economics

I recently went back to my hometown in Norway on holiday. Growing up in a country which is relatively cold, you’re not guaranteed warm weather for any length of time, so you need some other focus for the summer. For me and for most of my friends back home, the definition of summer is: strawberry season. For about two months of the year, Norwegian strawberries are sold at markets and stores all over the country. For these two months, it’s almost mandatory to bring strawberries to any social event – whether that be dinner parties, picnics, hikes, or a day at the beach. But all is not well with this annual jamboree: the cost of the berries has been soaring. The average price of Norwegian strawberries increased by 50% in 2021 compared to 2019.[1] The reason? Labour shortages – a problem which is not unique to Norway, but has been affecting the UK too.

Norwegian strawberry farms were hit by a labour shortage due to immigrants not being able to come to Norway during COVID. The UK has experienced a similar labour shortage in fruit-picking due to both COVID and Brexit. This made me think of how a decrease in immigration affects the labour market for picking strawberries and indeed for many other kinds of jobs too.

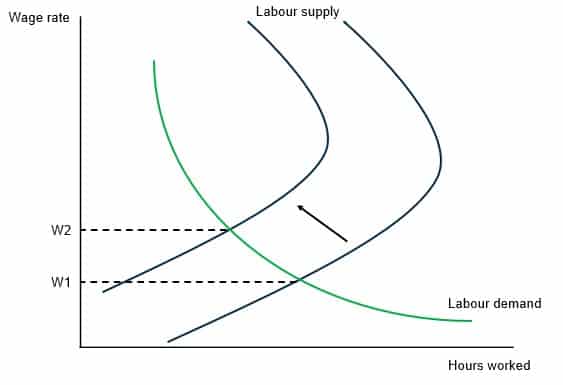

The labour supply curve, plotting the amount of hours worked against the wage, is depicted in the chart below. In general, the amount of hours worked increases with the wage. This is due to the substitution effect: when wages increase, the opportunity cost of not working increases, and one chooses to work more. However, there is also another effect influencing a worker’s trade-off between work and leisure: the income effect. As wages increase, the worker can afford the same amount of goods as before while working fewer hours. At the point where the income effect dominates the substitution effect, the labour supply curve becomes backward-bending.

Labour shortages in the market for strawberry pickers causes the supply curve to shift left

The supply of labour for a specific job depends on multiple factors, such as the available number of qualified people, how difficult it is to obtain the necessary qualifications, non-wage benefits, the wages and conditions of alternative jobs, demographic changes and immigration. Two of these are particularly relevant for the strawberry example: immigration, and the wages and conditions of alternative jobs. A decrease in immigration leads to an inward shift in the labour supply curve. If not met by an equal shift in the labour demand curve, this leads to an increase in wages. Furthermore, if a job is considered undesirable in a community, then the supply of labour for alternative, more desirable occupations will be relatively higher. This could be because working conditions are better, or wages higher, in alternative occupations.

This is exactly what happened in Norway during COVID and the UK during COVID and since Brexit: a fall in immigration caused a labour shortage. Strawberry farms were struggling to hire local workers, as strawberry-picking was not considered a desirable occupation. Alternative summer jobs offered higher wages and better working conditions. So, strawberry farms had to increase wages and the price of strawberries rose to cover the increased costs.[2] Similarly, the fruit-picking industry in the UK (and the food and farming sector more broadly) suffered labour shortages due to COVID and Brexit. For example, Sharrington Strawberries —an independent, family-run farm in Norfolk that produces top quality strawberries and asparagus — increased the wages of seasonal workers by 50%, but still could only recruit two thirds of the workers needed. This increase in costs was passed on to consumers. The National Farmers Union (NFU) noted the danger that rising prices would decrease the demand for local products, with consumers turning towards cheaper, imported goods.[3] Additionally, the labour shortages led to crops going to waste. The NFU estimated that food waste due to labour shortages in the first half of 2022 was worth £60 million.[4] [5]

The fruit-picking industries in both the UK and Norway are heavily reliant on immigrant workers. So, how can the fruit-picking industry get out of its labour shortage crisis? In Norway, the crisis was short-lived, as things returned to normal after COVID. It acted as a reminder of how important seasonal workers are to the industry, though. In the UK, a report published in June 2023 on the labour shortages in the food supply chain[6] makes a number of suggestions: improving access to migrant labour through an improved seasonal worker visa scheme, widening the eligibility criteria for the skilled worker visa route to include roles currently considered lower-skilled, investing in domestic workers and incentivising automation. Implementing these measures would reduce food waste, increase the revenues of the food industry, and help keep inflation of domestic food prices down. Most importantly, tennis fans would be able to continue enjoying English strawberries at Wimbledon. I will be going back home again in a couple of weeks and really hope this is before the end of the strawberry season. And who knows? Maybe I’ll get some sun whilst I’m there as well.

Strawberries (and some rare sun) in Norway this summer

[1] https://grontprodusentene.no/prisinformasjon/Jordb%C3%A6r/fra/2018/1/til/2022/53

[2] https://www.nrk.no/norge/jordbaer-plukket-av-nordmenn-blir-dyrere-1.15514140

[3] https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/9580/documents/162177/default/

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-into-labour-shortages-in-the-food-supply-chain

[5] Furthermore, Norwegian and UK workers were less productive than immigrant workers. This may have caused the labour demand curve to shift to the left. However, the dominant effect was the leftward shift in the labour supply curve, pushing up wages (and prices)

[6] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-into-labour-shortages-in-the-food-supply-chain

More by this author