A sideways look at economics

I rarely come across anyone who doesn’t know some part of this story. For some, it’s the cunning trick that brought an unnecessary war to an end. Others will talk about the lost man, who cleverly won the war but now can’t get home. Still others remember the faithful woman who waits for him, staving off suitors with her own gentle ruse. Many can quote the names as well as the incidents, which is to say that the story lives in them. I am of course talking about Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, which for almost three millennia have represented one of the cultural high points of the world. Who would dare attach a price tag to them? Heinrich Schliemann is probably the only one that could: after all, he lost his vast fortune to discover the ruins of Troy, and to excavate Mycenae and Tiryns, thus proving the historicity of the legendary places mentioned by Homer. I will content myself with arguing that the “price” of these stories, or rather their pricelessness, is a reflection of how early they were recorded and how they then survived unscathed through centuries of different people, religions, and customs.

Homer’s epic poems are so embedded in our consciousness that anyone can invoke them to effortlessly convey a complex situation to a broad audience. For example, in his latest Viewpoint column Fathom boss Erik Britton uses the Trojan Horse story to remind us why gifts — financial in this case — may hide dangers. The perils are clearly understood as soon as Erik invokes the popular allegory, and all that remains is for the writer to persuade us that a Trojan Horse situation may be in play. I am not sure whether Erik was also planning to spark interest in Homer’s poem, but he managed that with me. To be fair, a self-identified history geek like me only needed a reference to anything more than 200 years old to become intrigued about the origin story… Luckily, I like old stuff and modern online search engines in equal measures, so it did not take me long to find some answers.

The Iliad and the Odyssey are part of oral folklore poetry, and it is therefore difficult to establish whether writing them down contributed to their composition, or when they were first recorded. Some argue that Homer did not know writing and dictated his poetry to a scribe to ensure his works survived. Others believe that he did write his verses down. Most agree that they were passed down from mouth to mouth until they were popular enough to be recorded. But it wasn’t just word-for-word recording. The writing was enriched along the way by the poets who passed it on, tightening loose ends, smoothing and refining the language, and giving purpose. “The existence of a central plot, with beginning, middle and ending, as well as the complex techniques that were employed, compel us to accept that they could not be products of impersonal reciting, or indeed have been composed in a setting without writing”, scholars Maronitis and Polkas conclude.

The first official recording of the poems took place in pre-democratic Athens of the 6th century BC, when the dictator Peisistratus concluded that it would help his public image if the poems were mass-recited to people who attended his Panathenaic festival. However, the first systematic recording was carried out during the peak of the Hellenistic period (300-200 BC) by Alexandrian scholars and grammarians, such as Zenodotus of Ephesus, Aristarchus of Samothrace, and the female philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria (Hellenistic Alexandria was the first really ‘open’ society, in relative terms).

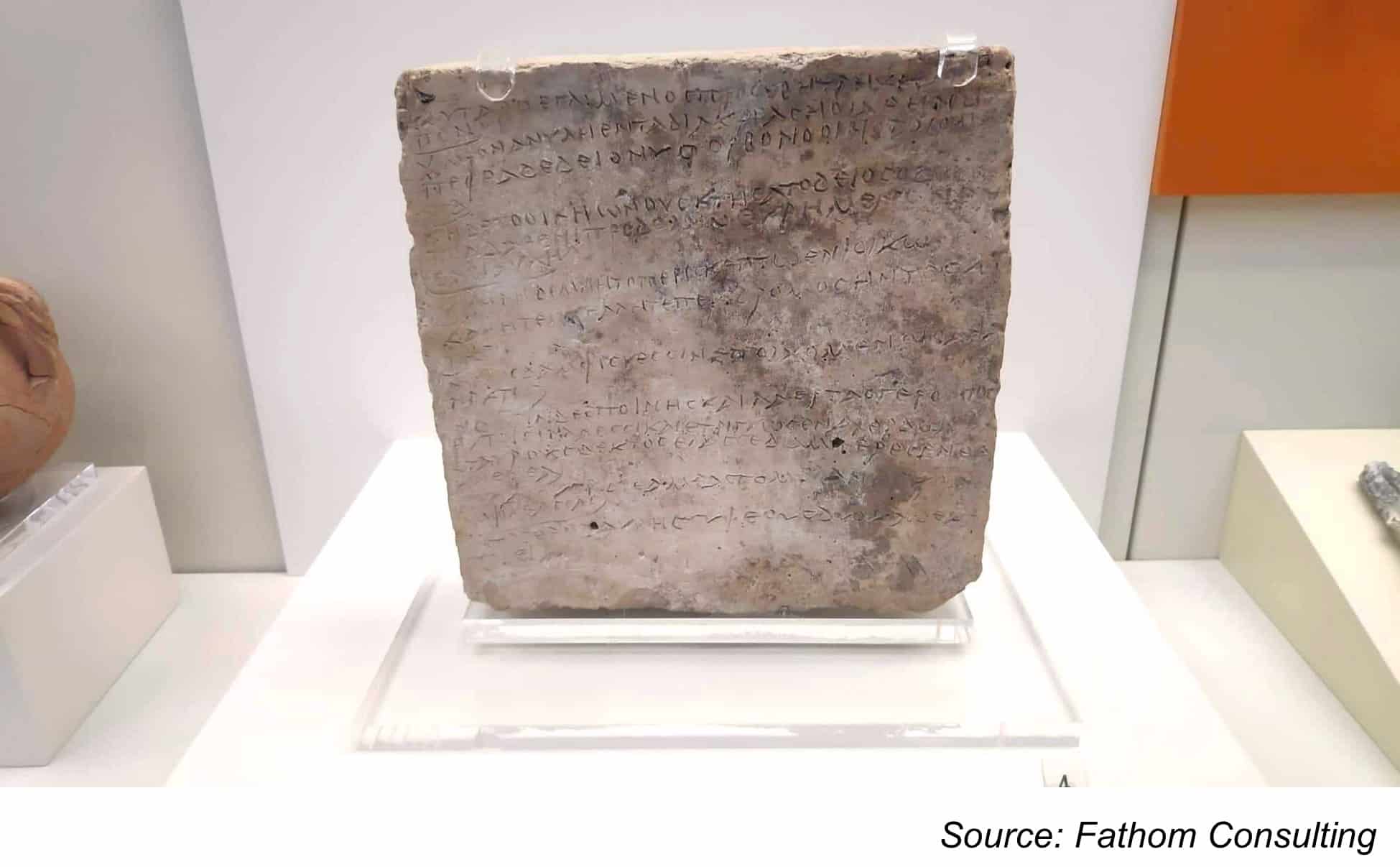

A fragment of the Odyssey dating from that period is the oldest written record of the poem we have. This marble tablet (in the photograph below), which recounts how Odysseus was reunited with his loyal shepherd, Eumaeus, was found in 2018 one mile east of Olympia. Coincidentally, I took this picture of it during a museum visit two summers ago. Why, some may wonder? Try to read it, if you know Greek; amazingly, it’s still possible to understand it, although much easier without your partner’s irritated gaze zeroing in on you (I had already lingered for ten minutes in front of the tablet, which was time well spent… in my opinion).

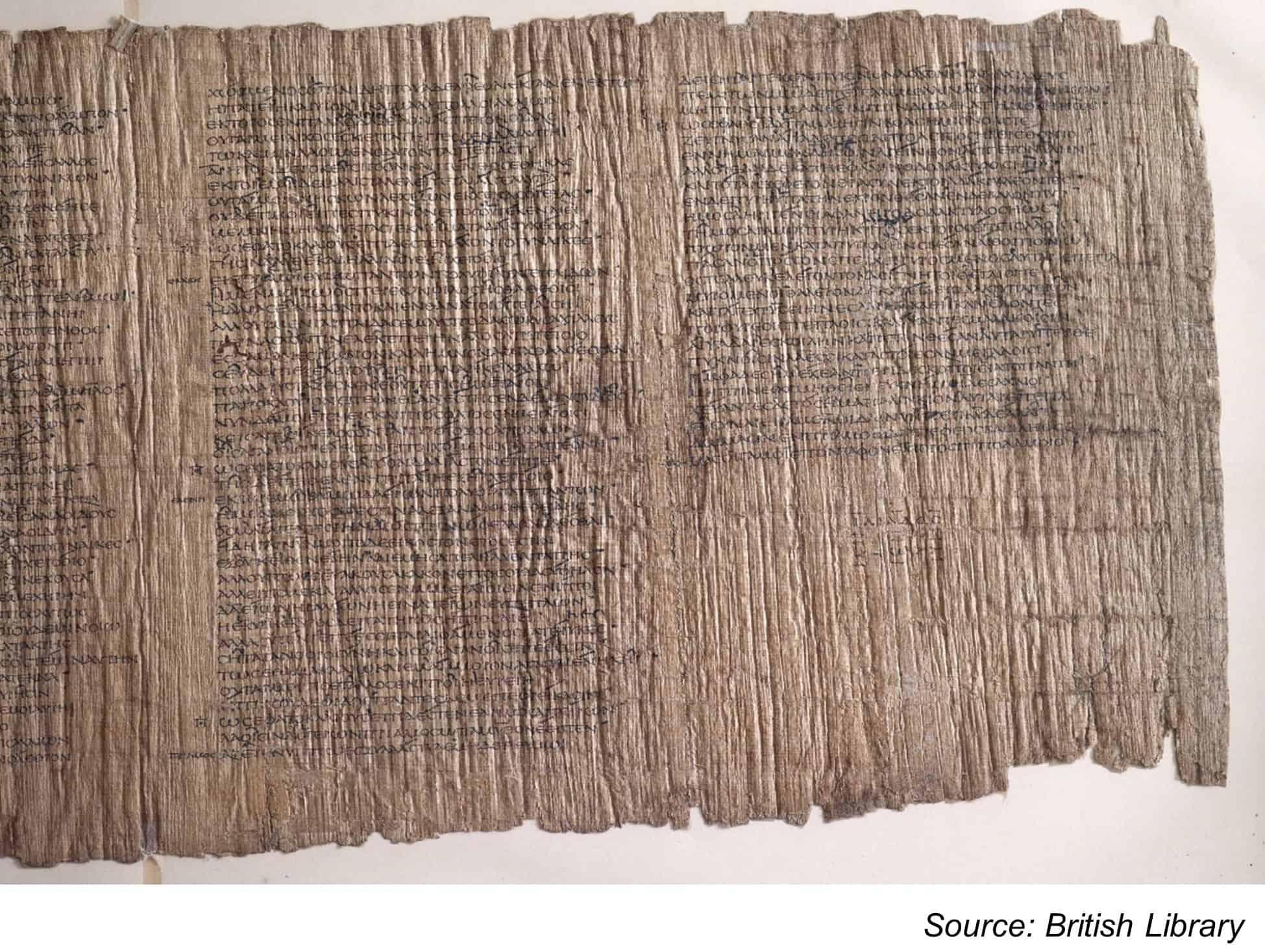

The Hellenistic versions of the text were preserved over the ensuing centuries with the help of the Romans and their reproductions on clay tablets, papyrus and paper, either in Greek or Latin. Somehow, the story and its values were so universal and so popular that between the 2nd and 11th century AD both Christians and Muslims alike picked up the copying baton, not hindered by the strict religious doctrines and wars of those times. More importantly, the copies made in that period are what has handed the story to the “modern ages” — to us. The most popular example of this is the Bankes Homer papyrus, created in the 2nd century, discovered in the 1800s and now safeguarded in the British Library. That copy contains the bulk of the text of the final book of Homer’s Iliad (even without the first 126 lines, the papyrus is 2.5 metres long when fully unwrapped).

Copies like the Bankes Homer papyrus are invaluable not only for what they contain — a story dating from at least the 8th century BC, perhaps older — but also for what they represent: the human struggle and ingenuity that they describe, the unbroken tradition that has handed them on, and the immense influence these stories have exerted on generations of people through the millennia.

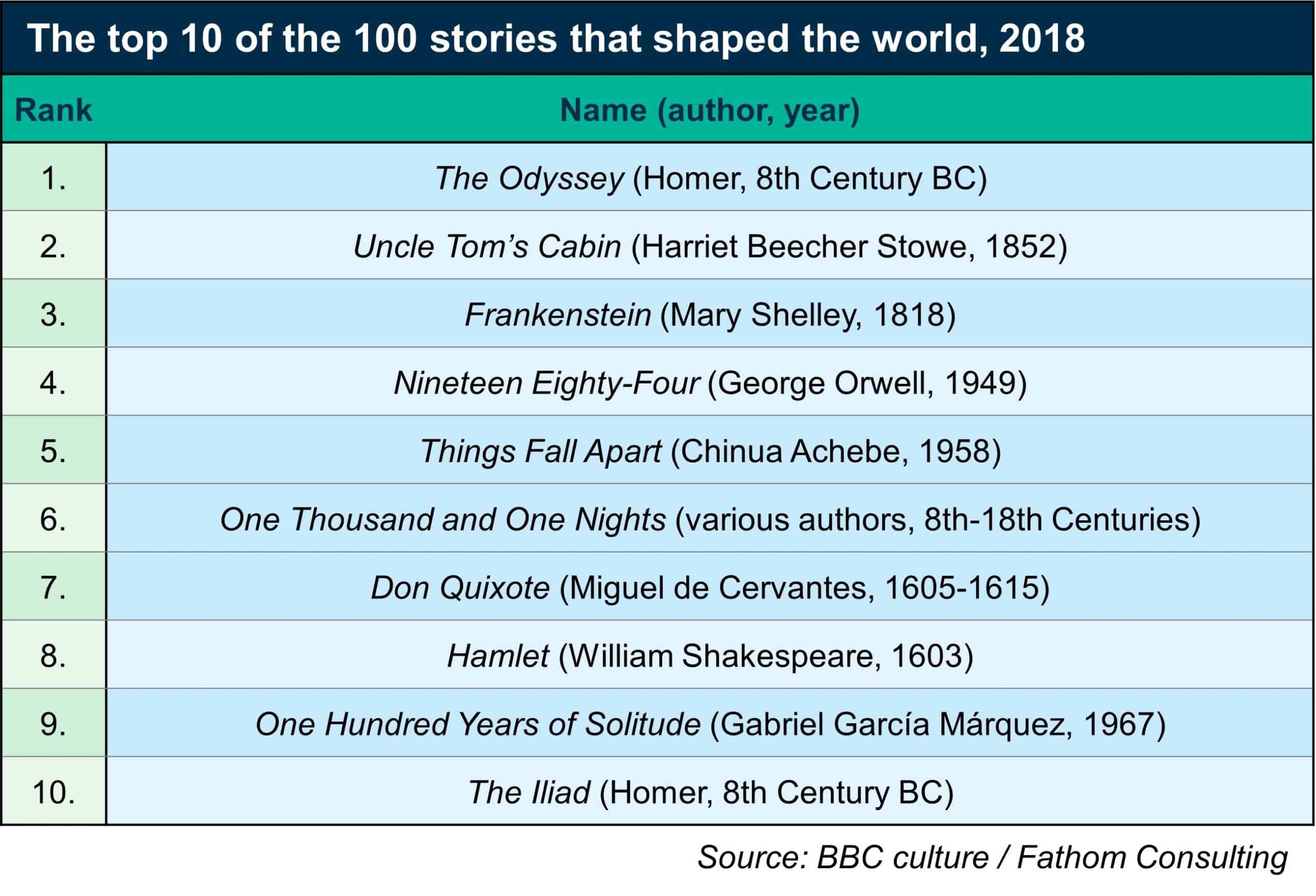

Homer’s epic poems are not simple adventure stories, they are about characters and their struggles. The Odyssey, for example, is about a man returning home. He is a husband away from his wife, a father who did not witness his son growing up, a warrior whose war is over, a leader whose men all die. Every reader can find something new in this poetry, and every writer can take inspiration from this story; writers from Dante to James Joyce to Margaret Atwood have done so. It’s not surprising then that in the list of the 100 stories that shaped world, the Odyssey sits at the top, and the Iliad in the tenth place. Their human centrism offers timeless catharsis to readers, listeners and, since the mid-20th century, viewers. I am therefore inclined to agree with the voters of this BBC 2018 poll: if any story can be considered the greatest tale ever told, Homer’s epic tales have a better claim than most.[1] It was not mere luck that these tales survived in written form for so long, it was only natural for something so priceless. Needless to say, these Greek-turned-global epic poems will continue to survive, free of charge to all.

[1] The 2018 BBC poll was widely representative and tried to keep selection bias to a minimum. The 108 voters were from 35 different countries — from Uganda and Pakistan to Colombia and China — with only 51% of them claiming to have English as their mother tongue. The critics, scholars and journalists who voted were 59% female, 41% male. They were asked to nominate up to five fictional stories they felt had shaped mindsets or influenced history. Their final choices included novels, poems, folk tales, and dramas in 33 different languages. You can find the voting details here.

More by this author

Strawberries are not the only juicy prospects at Wimbledon