A sideways look at economics

Imagine visiting your local supermarket tomorrow morning, picking up your usual sourdough and handing your £5 note to the cashier, only to have them decline it. “That’s just a worthless piece of paper” they claim. You try paying by card. “That’s not even real!”. This isn’t just an imaginary nightmare for those on the London sourdough hype, which now includes myself, it is a surprisingly possible reality.

This scenario feels slightly ridiculous, because it highlights something we rarely stop to consider — how deeply trust underpins not only our economy but much of our daily lives. Every transaction, every relationship, even every job relies on mutual trust. Money is perhaps the clearest example of this concept. Its value lies not in the paper itself but from the trust that everyone else will also recognise its value and accept it, including the cashier. If they don’t… well, it is probably worth less than the paper it is printed on. This logic applies beyond money too. If tomorrow you suddenly doubted your employer would pay your salary, you’d likely stop turning up to work. If you lost trust in a friend, your relationship would quickly deteriorate. The influence of trust is subtle, but it becomes glaringly obvious when it disappears.

Take the notorious hyperinflation of Zimbabwe. Flawed economic reforms, which resulted in sustained price rises, broke the trust in the government and led to citizens quickly losing confidence in the ability of their money to hold its value. At the height of the crisis in November 2008, Zimbabwe’s year on year inflation was close to 90 sextillion (that’s 21 zeros). To put that into perspective, throughout the recent inflation spike in the UK, inflation peaked at a measly 11%. What was all the fuss about?

But even in the UK we aren’t immune to this sudden loss in confidence in our institutions. Take the collapse of Northern Rock in 2007, the UK’s first bank run in over a century. What began as a request for liquidity support soon spiralled as, after seeing the headlines, panicked customers rushed to withdraw their savings. The sight of growing queues outside branches reinforced that panic, turning speculation into reality. Confidence is fragile and once doubt creeps in, it can spread rapidly, not necessarily due to a rational reassessment of facts, but because people are highly influenced by the behaviour of those around them.

To establish trust, institutions need to deliver consistently and reliably. The Credibility Thesis suggests that trust in governments or corporations doesn’t persist through inertia but on whether they effectively serve their intended function. When they perform well, confidence grows and trust is built. But, once this reliability is called into question, that trust and credibility erodes quickly, whether you are a newly established currency or a 150-year-old bank. Restoring confidence can be far more difficult than maintaining it as Zimbabwean policymakers have found. The country is now on its sixth attempt at forming a new currency since the start of the crisis while around 70% of all transactions in the country are done in the, more trusted, US dollar.

But let’s stop dwelling on the negatives, it’s time to get some confidence back into this TFiF. These effects don’t just go one way, and confidence isn’t just about preventing instability. At its most basic level, confidence helps offload some of the world’s complexity by allowing us to assume a certain level of predictability. A climber who has faith in their harness doesn’t have to worry about what happens if their grip slips. This offloading of uncertainty creates the conditions for us to take more risks and make decisions with greater conviction. This applies even to confidence in one’s own abilities. Research has found that self-efficacy (an individual’s belief in their own abilities) was a significant predictor of academic achievement, independent of inherent personality traits. Likewise, confidence in sport doesn’t just reflect ability but actively shapes it, with self-assured athletes found to be more likely to take decisive action, persist through setbacks, and perform at higher levels.

There are benefits for the economy as well, of course. When businesses feel optimistic about the future, they invest in new projects, hire workers and expand production. When consumers are confident in their financial stability, they spend more freely. Investors, too, are guided as much (maybe too much) by sentiment as by fundamentals, with market swings driven by changing expectations rather than current realities. Studies have found perhaps unsurprisingly that confidence positively affects growth, particularly when confidence is low, such as amid recessions. Here confidence can act as a catalyst for policy interventions.

Keynes famously described confidence-driven decision making as “animal spirits”, the psychological factors that influence economic behaviour beyond the hard data. In times of uncertainty, when confidence collapses, businesses and households reduce spending out of fear, reinforcing downturns. But when confidence begins to grow, even before fundamental conditions improve, it can kickstart a recovery. This is why interventions, such as stimulus spending or central bank assurances, are often aimed as much at restoring confidence as at directly boosting economic activity. Confidence, in this sense, is not just a byproduct of economic conditions but a key driver of it.

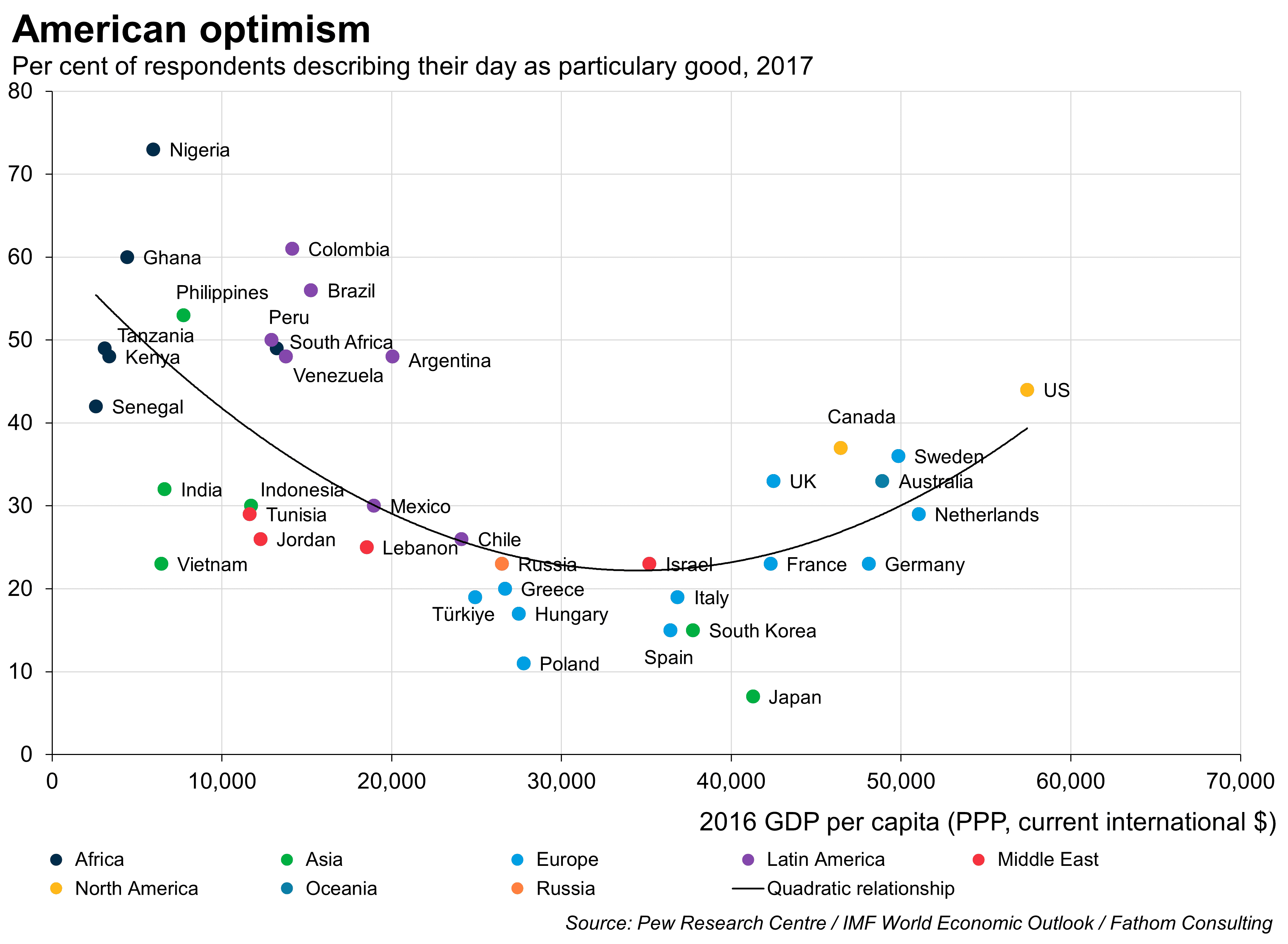

Just as someone who is assured of themselves takes bolder decisions, so too do nations. Nowhere has this been clearer in modern history than the US, ‘the land of opportunity’. American optimism, as Greenspan and Wooldridge argue in Capitalism in America, has fuelled waves of innovation and reinvention through the belief that setbacks are temporary and that new opportunities will emerge. It underpins the country’s embrace of creative destruction, where industries rise and fall not as a sign of failure, but as part of progress. Surveys by the Pew Research Centre quantified this optimism, finding Americans were an outlier compared to their peers of a similar living standard when describing their day as “particularly good”.

Japan’s ‘Lost Decades’, by contrast, offers a case study of the effects of a lack of confidence. Since the 1990s, uncertainty has shaped both corporate and consumer behaviour, leading to decades of low growth and weak inflation. Rather than seeing change as an opportunity, businesses have been reluctant to invest and households have preferred to save rather than spend. Surveys from the Bank of Japan suggest that risk aversion, rather than just economic fundamentals, has been a key factor in stagnation.

If it is so powerful, then why aren’t we always confident? And why doesn’t Japan give itself a pep talk in the mirror and get back to booming growth? Well, even if we could control it, it isn’t a magic solution. If we were to become perpetually confident, we would become reckless and overlook real dangers. The financial crisis of 2008, for example, was made possible by a widening gap between confidence and actual risk. At the same time, confidence is fragile. It is built on faith, not certainty — faith in others, in institutions, or even in the nation as a whole. There will always be shocks that shake it, but ironically this is when confidence becomes most valuable. The challenge is not just having confidence but in knowing when to use it.

More by this author