A sideways look at economics

As I was swiping decisively through my best friend’s online dating account last Saturday, it struck me that in many respects the online dating market isn’t dissimilar to markets others of us are more familiar with, such as the online shopping market.

Indeed, both are booming, with the reasons below being valid for rejecting either a date or a pair of jeans:

1) Too big

2) Too small

3) Not as pictured

4) Doesn’t suit me

5) Damaged

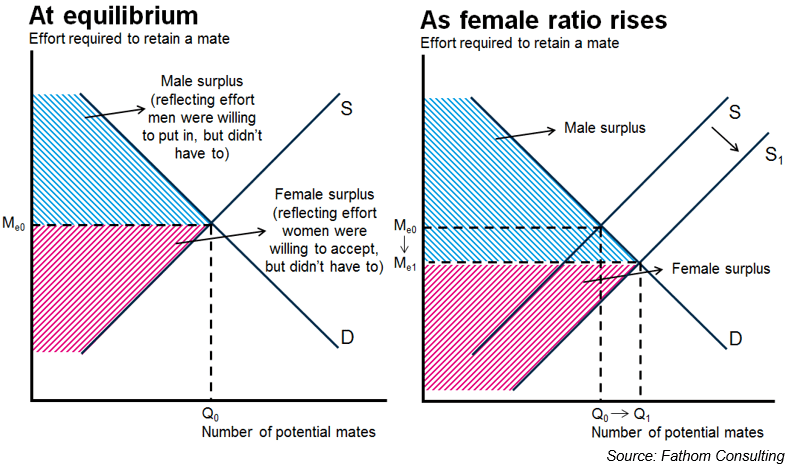

Another commonality is that retail websites such as eBay and Etsy bring together buyers and sellers, while online dating platforms such as Bumble and Plenty of Fish expand the dating pool, bringing together potential suitors. And although the latter doesn’t require the exchange of money, it certainly has a price. That “price”, it would seem, is also dictated by supply and demand. Or, put simply, the ratio of men to women.

As explained by another friend, who happens to be a Tinder success story,[1] “it’s not that ‘he’s just not that into her’, or that ‘she isn’t putting herself out there enough’, it’s just that there aren’t enough of him to go around!”

It transpires that this phenomenon is a common problem in American colleges, with what author Jon Birger refers to as the ‘man deficit’ helping to explain not only the college hook-up culture but also declining rates of marriage.

He found that in colleges where men were in oversupply, with a male-to-female ratio greater than 1, the dating culture was more likely to emphasise romance and courtship. A consequence, he suggests, of men bidding against each other.

There’s ample evidence of this in China, where substantial cash gifts and ownership of a property have become prerequisites for securing a bride. In other cultures, where the practice of polygyny sees large swathes of the male population priced out of the market, gender imbalance has been linked to social instability and even war as men join the military in a bid to avoid bachelorhood.

In Birger’s study, however, women were in oversupply more often than men; there are more female than male graduates in the US. According to Birger, when the terms of dating swung in the men’s favour, it created a more ‘sexualised’ dating culture.

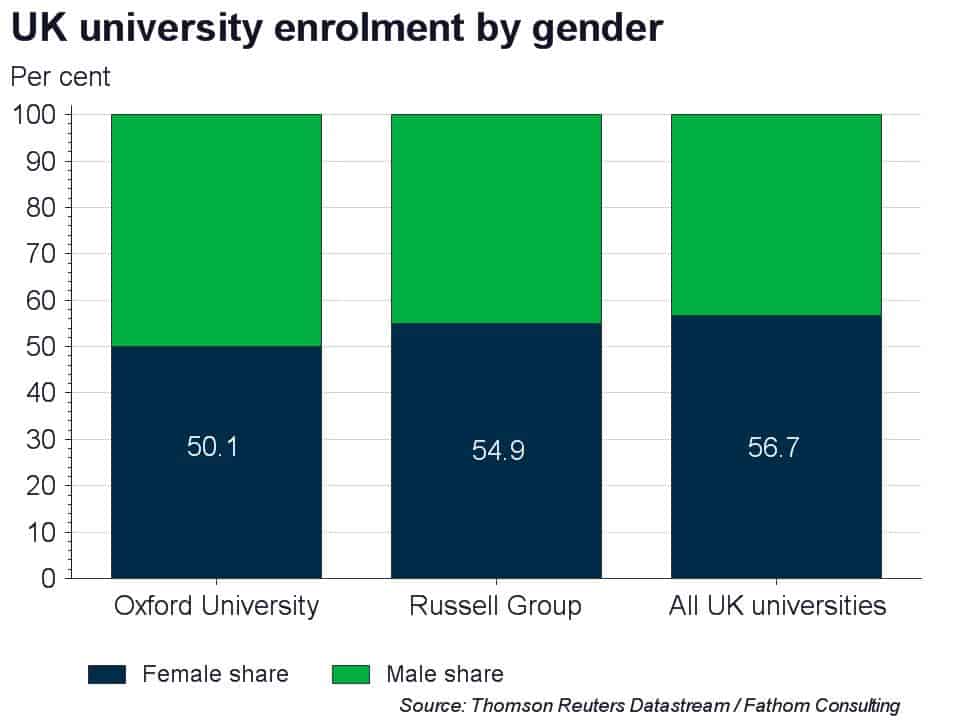

The ratio in the UK isn’t dissimilar to that identified by Birger, with women accounting for 57% of higher education enrolments (a ratio of approximately four women for every three men). That varies, of course, with Oxford University boasting a more even playing field for its female students!

While there’s a mass of material on this subject, you don’t need to refer to the various primate experiments to confirm Birger’s findings. Instead, one is underway far closer to home (and some of our hearts) in the form of reality dating show, Love Island.

In the show, an equal number of single men and women move to a luxury villa in the hope of finding love, or, as the saying goes, ‘their type on paper’. But to remain on the island and avoid elimination, contestants must couple up and win the hearts of each other and the public. All’s well until the producers introduce additional islanders, tipping the gender balance.

This lopsided ratio, as Birger’s study suggests, changes the contestants’ behaviour. Indeed, the introduction of additional women has seen the men, like their primate equivalents, increasingly likely to play the field and abandon their existing mates. Need I say more than “Adam”, this year’s lothario!

In this simple model, as the supply of women increases there are too few men to go around and it becomes a race to the bottom. The women either accept a lower “price” (aka the degree of male affection required to achieve a coupling) or are left on the shelf. Alternatively, they flaunt other attributes (as we’ve also witnessed), in the hope that they’ll be deemed more desirable than the competition. This, my other half argues, has been the female contestants’ downfall, with their territorial marking and “she ain’t having my man” attitude enough to put anyone off. Note taken.

But for others, such as my friend, switching dating sites may improve her luck, avoiding what (in economic jargon) is termed a ‘market failure’. If switching dating sites fails, applications to star on this season’s Love Island remain open. You’ll have heavy competition though, with more applicants to this year’s show than to Oxford and Cambridge Universities combined. Who said that romance was dead…

[1] As we go on to discover, her success on Tinder may not be due to charm alone. While there are conflicting reports of online dating ratios and member usage, most seem to agree that Tinder has a higher proportion of men to women, turning the tables and giving women the leverage.