A sideways look at economics

Ski trip season is upon us, and a recent conversation with a person in the fashion industry, whose main customer base is in the Alps, left me puzzled. They said that for customers to consider purchasing their clothes, they had to increase their prices. However, the rule of demand, one of the basic principles of economic theory, states that the demand for a good decreases as its price increases. I discussed this with some colleagues during lunch one day, where I discovered that this type of good has a name: a Veblen good.

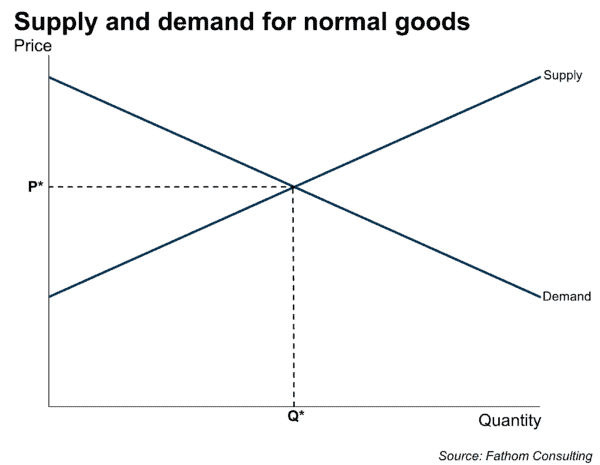

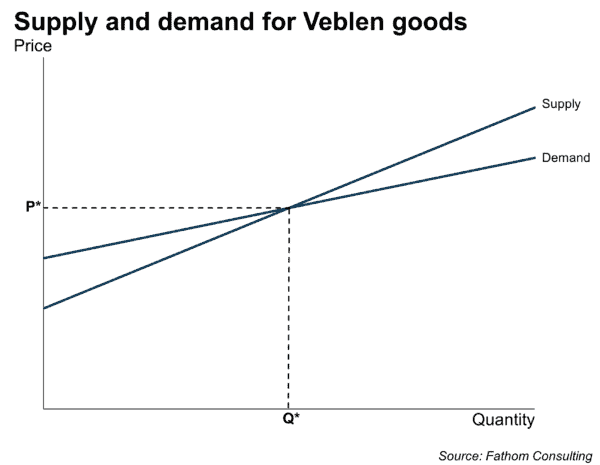

A Veblen good (named after economist Thorstein Veblen, who first introduced the concept as ‘conspicuous consumption’ in his book Theory of the leisure class, 1899), is a high-quality, exclusive luxury good and a display of wealth. The customer is willing to pay a premium for the socio-economic status that these goods convey. Typical examples are sports cars, designer bags and jewellery. These goods do not necessarily have a higher functionality than other, lower-priced items (it is perfectly possible to find a leather handbag that is cheaper than a Chanel bag). The customer’s increased willingness to pay for this item compared to another item of the same quality stems from the social status that is attached to a certain brand. It can be explained through two effects: 1) increased utility/pleasure from the social status that these goods signal and 2) the keeping up with the Joneses effect (if my neighbour buys a Tesla, I now want a Tesla, even if I have a perfectly functional car from before). With the growing power of influencers, particularly on younger generations, perhaps the latter should be renamed the keeping up with the Kardashians effect. The graphs below portray the supply and demand of normal goods (demand decreases as the price increases) and Veblen goods (demand increases as the price increases).

Who are the consumers of conspicuous goods? Demand for Veblen goods looks to be higher in metropolitan areas. A study on conspicuous consumption in the US, using data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey in 21 metropolitan areas, concluded that city size and population density are positively associated with conspicuous consumption.[1] Interestingly, consumption of non-visible luxury goods, termed by the study as ‘inconspicuous consumption’ (such as wine and travel), increases with higher education. It is not just the top earners that spend money on conspicuous goods: According to GlobalData, the brackets of Americans with a household income less than $50,000 account for almost as large a share of luxury goods consumers as the income bracket above (household incomes up to $150,000 per year).

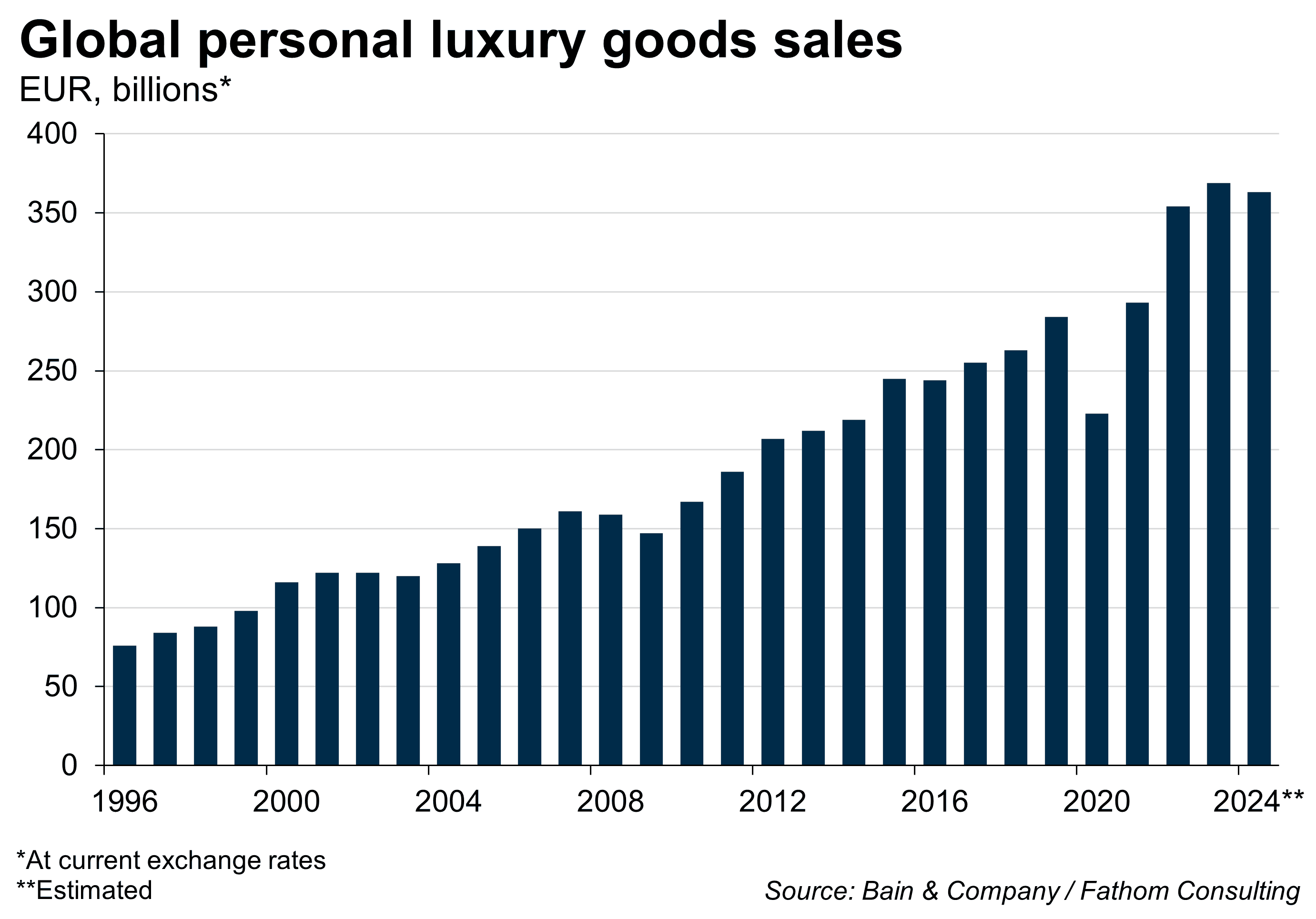

Looking at recent trends, the luxury sector struggled during Covid, but picked up from 2021 to 2023, as customers (in particular in the US), were dipping into their pandemic savings. Note that the increased sales are not necessarily due to customers buying more goods, but also due to inflation in the price of luxury goods. The reopening of the Chinese economy post-Covid also contributed to this growth. However, sales of personal luxury goods decreased in 2024, contrasting to its upward-sloping trend (excluding Covid). Furthermore, 2024 saw a shift from luxury goods to luxury experiences, with the only four luxury categories experiencing growth relating to experiences.[2]

Will the market for luxury goods be able to return to a growth trajectory? According to estimates from Bain & Company (2025), the customer base for luxury goods decreased by 50 million from 2022 to 2024. To continue growing, the luxury goods market is dependent on leveraging the potential of growing markets as customer bases. Latin America, India, Southeast Asia, and Africa are expected to add 50 million upper- and middle-class luxury consumers by 2030 (Bain & Company, 2025). In 2024, Japan had the largest growth in luxury sales, whereas China’s luxury market went through a downturn due to a lack of consumer confidence. Among Gen Z, demand for luxury goods in China and Southeast Asia is growing, in contrast to Japan and Western countries, where demand is slowing. Whether 2024 marks the beginning of a slow-down in the luxury goods market will not only depend on its ability to leverage growing markets, but also younger generations.

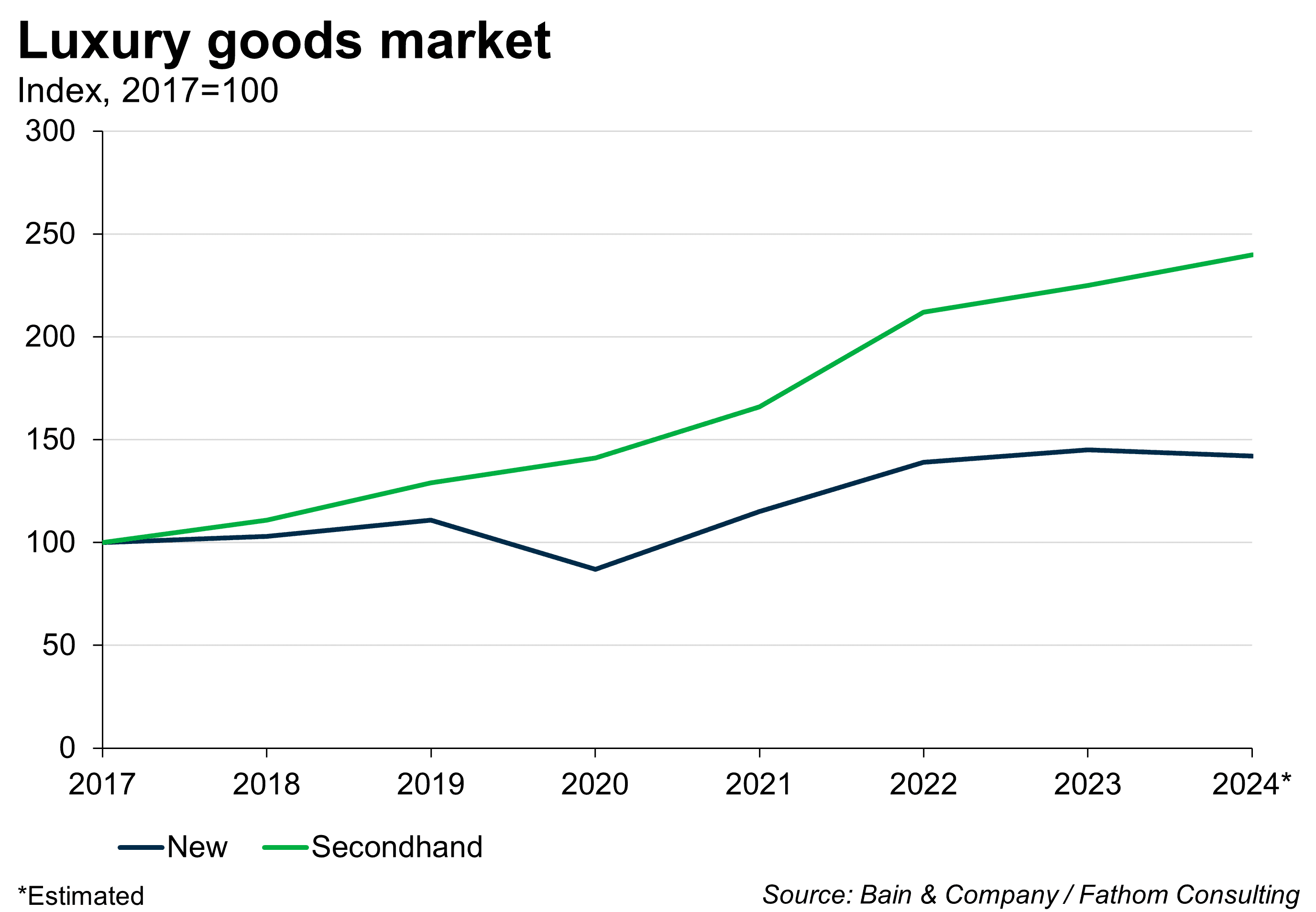

Among Gen Z, there is an increased focus on the second-hand market. The market for second-hand luxury goods is growing at a faster rate than the market for new luxury goods, growing by 140% since 2017 (compared to 42% for new luxury goods). Not only is the second-hand market cheaper, but it can be seen as a reaction against fast fashion and over-consumption. A focus on sustainability can work both as an advantage and a disadvantage for luxury goods: the focus on quality over quantity can be leveraged by the luxury industry, if their customers perceive the price premium as a quality premium. On the other hand, a reaction against overconsumption may include customers only buying the things that they actually need, which may lead to demand for goods that are bought purely as status symbols decreasing. Perhaps there will be a shift in the luxury industry from Veblen goods displaying status to high-quality items made of long-lasting materials.

So, is 2024 the beginning of the end of Veblen goods? Perhaps, considering Gen Z’s increased focus on value for money and the rise of the second-hand market. On the other hand, this is also the generation of influencers and social media, giving luxury brands a new marketing platform to increase sales. Demand for luxury goods among Gen Z poses a somewhat mixed picture; with growing interest in China and South-East Asia, but slowing in Japan and Western countries. Maybe, with the rise of social media, Veblen goods are taking a different form, with the only luxury categories experiencing growth in 2024 being linked to experiences. Perhaps posting a photo of your recent ski trip to the Alps is a new form of displaying wealth.

More by this author

‘Thinks and Drinks’ and the sunk cost fallacy

Korea’s jeonse housing bubble is bursting