A sideways look at economics

In the great 1957 film “Twelve angry men” (from the play of the same name written by Reginald Rose), Henry Fonda stars as the lone hold-out in a jury of twelve, unpersuaded by the evidence against the defendant in the murder case they are hearing. For the remainder of the film, he gradually cajoles and persuades the other eleven jurors to agree with him and acquit the defendant. The other jurors are keen to get back to their normal lives, but Henry Fonda’s character is unwavering in his commitment to due process, and is ultimately victorious.

The film is a romantic vision of the power of dissent; of challenging a lazy orthodoxy with the stubborn voice of reason, which in the end prevails. It’s an inspiring message, not least for small independent consultancies like Fathom!

The real world rarely conforms to that romantic ideal. Dissent rarely prevails. But it is interesting and romantic, even when it fails.

Dissecting the phraseology of central bank statements, poring over speeches and generally trying to read the runes of central banks has become a key responsibility for many macroeconomists. Trying accurately to predict the direction and timing of future changes in interest rates, or less conventional monetary policy tools, is big business, and markets can turn swiftly on minor wording changes. So in the world of ‘central bank watchers’, few clues are deemed more important than if a committee member begins to vote for a change in policy.

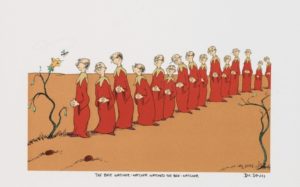

In “Did I ever tell you how lucky you are?”, Dr Seuss imagines a village in which the harvest has been poor, and the blame is attributed to the single bee, who is thought to be slacking. So the village nominates a ‘bee-watcher’ to make sure the bee does its job. But nothing changes. The villagers conclude that the bee-watcher must be slacking, so they appoint a bee-watcher-watcher…and so on, until the whole village is engaged in a totally pointless activity. Something similar could be said about the industry of central-bank watchers around the world…

If nothing else, being a dissenter on a policy committee guarantees you the close attention of the astonishingly vast community of central bank watchers. The voice of dissent is heard and amplified by that community, which is undoubtedly a good thing.

But does dissent prevail, per the romantic vision of Reginald Rose? This is a timely question, given the close vote against a rate hike from the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee yesterday. Our previously published analysis of their voting patterns found that there was typically very little information regarding the future path of UK bank rate from the patterns of dissent on that Committee. Of 40 periods of dissent since its inception in 1997, only a little more than half of the time did the majority eventually form behind the dissenter(s). In the case of voting for a rise in Bank Rate, the ‘success’ rate of the dissenter was 40%. Hardly convincing: more often than not, dissenters on the MPC either change their minds or leave the committee.

But perhaps it is even more surprising that, having extended this analysis to the US Federal Reserve’s FOMC, we find that there is even less information in dissenting votes there, in the most important central bank in the world. Over the same period, there have been 26 instances of dissent, in which dissenters have been ‘successful’ just 15% of the time.

It is perhaps ironic that what should be the strongest signal for future monetary policy, the voting of decision-making committees, carries little or no significant information about the next move. In the case of the US, dissenters are more than five times as likely to give up (or leave) than be proved right.

The fact that dissent carries no significant signal of the direction of any future move in interest rates does not prevent the industry of watchers from getting excited when it occurs. And that excitement means that dissent can move markets in the short term at least. Which in turn means more power to the elbow of the dissenters – something that makes the romantic in this author happy.