A sideways look at economics

It is nigh on 200 years since David Ricardo first set out his theory of comparative advantage in his classic work ‘On the principles of political economy and taxation’. Since that time it has been a unifying belief among economists that a country should channel its resources into producing only those goods and services in which it has a comparative advantage, exporting whatever it does not need around the world.

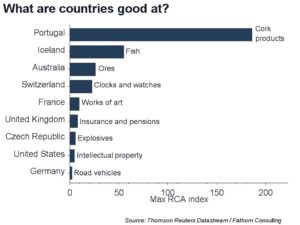

But what are different countries good at? Revealed comparative advantage (RCA) provides one metric. A country’s RCA in the production of, for example, meat is given by the share of meat exports in all of that country’s exports, relative to that same figure for all other countries. If a country’s RCA for a particular good or service is greater than one, then it is relatively good at producing that good or service. And the higher is the RCA, the better it is.

Over the past few weeks, we have put together RCAs covering more than 100 industry sectors across more than 200 countries. In the chart below, we record the industry sector with the highest RCA across a subset of OECD economies. There are few surprises. The French, it seems, are pretty good at works of art. As a share of total exports, they export close to ten times as many works of art as the typical country. It turns out they are not bad at wine (with an RCA of 4.5) or cheese (with an RCA of 2.6) either. The Icelanders are brilliant at fish, with an RCA of 55.2, while the Czechs are a dab hand at explosives, with an RCA of 5.6.

Who would feel the pinch if the world took a sudden lurch in the direction of greater trade protection? Portuguese cork manufacturers may have the most to lose – at 186.1, their RCA is the highest for any industry, in any major economy. By contrast, the highest RCA of any industry in Germany is just 2.3. That is the lowest maximal RCA of any country in the world. Germany, it seems, is good at exporting everything. Really this should come as no surprise – Germany has, after all, managed to persuade its major trading partners to tie their exchange rates irrevocably to its own at rates that, after more than a decade of superior German efficiency gains, are now wildly uncompetitive.