A sideways look at economics

“I work all night, I work all day, to pay the bills I have to pay

Ain’t it sad

And still there never seems to be a single penny left for me

That’s too bad”

‘Money, Money, Money’ — arguably one of Swedish pop group ABBA’s most popular hits — celebrated its forty-first birthday last week. The song tells a familiar tale of a young woman struggling for money. It’s a story we can all relate to. Cash — we all need it, don’t we?

Well, perhaps not. The Swedish Riksbank, eager to be at the forefront of monetary innovation, is one of a growing number of central banks investigating whether the world would keep turning without cash. The answer they are likely to find is yes!

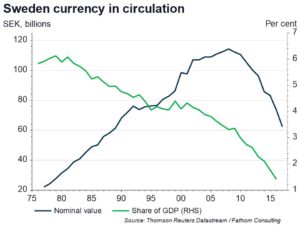

There’s no suggestion that the concept of money will disappear altogether, but the development of electronic banking and, more recently, the invention of cryptocurrencies, threatens to decrease the role that cash plays in the economy. In Sweden, the use of cash is in decline, both in absolute and relative terms. The introduction of new technologies such as contactless cards, Swish, and both Apple and Android Pay, has accelerated the trend and it is expected to continue after an EU law banning card transaction fees comes into force next year. Already, in some areas of the country it has even become challenging to find cash at all!

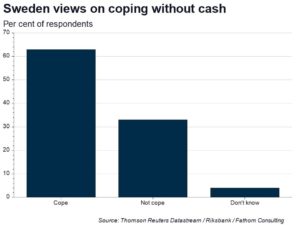

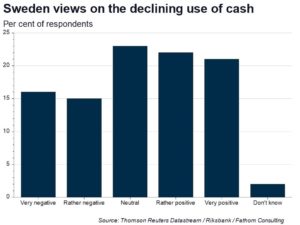

In Sweden, it appears that consumers simply prefer to purchase goods and services using their debit and credit cards. A decreasing role for cash is evident elsewhere too, and it’s not just in developed economies. In Kenya the traditional path of monetary evolution has been bypassed and mobile money has thrived, with transactions using mobile money now valued at approximately 47% of GDP. As the decline in cash demand continues, one must wonder whether it’s needed at all. Arguably, central banks are duty-bound to investigate whether the world will keep turning without physical currency. Moving to a purely digital currency is a radical proposal, but there’s good reason to suspect that the change is inevitable; according to a 2016 Riksbank survey the public seem to support it.

What’s behind this decline in cash?

Many businesses currently accept both physical currency and card payments. In a sense, you could almost view these as two currencies, circulating side-by-side at a fixed one-to-one exchange rate. Discussions concerning parallel currencies have a long history and can be traced back to Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristophanes. Historical experience suggests that where currencies have existed in parallel, the stronger currency will force the weaker out of circulation. Nobel laureate Robert Mundell’s characterisation of this is that: where two currencies exist side-by-side, “cheap money drives out dear, if they exchange for the same price.”

How, you might ask. Well, consider the case of a customer purchasing a good from a shopkeeper. The customer has two currencies (one cheap and one dear) and both are considered legal tender. The customer can pay using either the cheap currency or the dear currency. Obviously, they will pay with the cheaper currency, as it entails less cost to themselves. In such an economy, the dear currency will be infrequently used and transactions will be conducted primarily using the cheapest form of payment.

The theory suggests that one currency will drive the other out of circulation. But this still leaves us with a couple of questions to answer.

For instance, what makes one currency cheap and another dear?

In the past the answer was simple and depended on the purity of a minted coin (i.e. its value if melted down). In modern times, this is a more complex question. If two currencies are considered legal tender, then one must perform some function that the other does not (i.e. there must be some benefit to holding one currency and not the other).

Do electronic currencies constitute a cheap currency?

Possibly. Compared to physical currency, electronic money is: less burdensome to carry (a few plastic cards vs. pockets full of coins); more readily divisible (cashiers don’t struggle to find the right change); and more secure (a card is useless without the pin). In other ways, however, it’s less desirable. For instance, facilitators of card payments (Visa, Mastercard etc.) often impose charges, which are sometimes passed onto consumers.

So, is the end of cash approaching?

Economic theory predicts that the cheap money will eventually oust the dear. This change is unlikely to be completed soon — it may not even happen in our lifetimes — but it will surely happen at some point. Questions remain about how a purely digital currency would be implemented. The most radical of proposals would circumvent the traditional banking system altogether and give consumers accounts at the central bank. It is more likely that private-sector banks will hold money for customers in a near continuation of the present system. Central banks’ ability to continue setting interest rates in a post-cash world is unlikely to be significantly impaired and might even increase.

But would governments favour such a change? After all, removing physical cash from a central bank’s balance sheet would eliminate the seigniorage revenue available to its sovereign. Arguably, however, the government could offset this loss through introducing small transaction charges. Even without changes to the current system, public finances might be expected to improve. At present, cash transactions provide a great deal of anonymity and help to facilitate the black economy. Greater transparency would therefore give governments access to a new source of tax revenue — finance ministers would be rubbing their hands together with glee. ‘Money, Money, Money’ indeed!