A sideways look at economics

Betelgeuse is a red giant star sitting on the right shoulder of the hunter Orion, who rises on the southern horizon in winter in the northern hemisphere, announcing the arrival of bare branches, frost, plumes of breath in the night air: winter. On a clear night, its redness and its size are evident to the naked eye.

Betelgeuse is approaching the end of its life cycle. It will explode into a supernova any day now (well, at some point probably within the next million years or so). That process is inexorable. Barring some collision, or tumbling into a black hole, it was inevitable from the moment the star was born that it would eventually die in that way. And, moreover, had we sufficient information about its construction, we could estimate the timing of its death within fairly small tolerances.

Stars have life cycles that obey the laws of physics.

The same is not true for economies. The ‘business cycle’ is a concept often invoked by people who argue that we’re ‘due’ another recession. As though the processes underlying the cyclical behaviour of the economy were as inexorable as they are for Betelgeuse. But they are not. There is no ‘typical’ length of an economic cycle. The mean is honoured more in the breach than the observance.

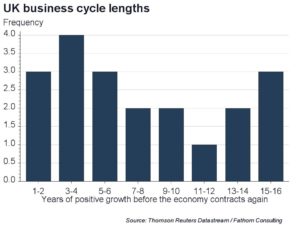

In the UK, where the data go back furthest, the number of years of positive growth that take place between successive economic contractions is distributed more or less uniformly over the range two years to sixteen years. And that range is probably a function of the fact that – even in the UK – we only have data back to 1830. Had we a thousand years of reliable economic data it is likely that the range would be wider still.

Each economic cycle has its own life story, and its own longevity. The duration of a recovery alone tells us nothing about the likelihood of a coming cyclical downturn. To assess that likelihood, you need to understand the life story of that recovery, and its genealogy too. Right now, for example, we should be very concerned about imbalances in the British economy – things like the ratio of asset prices or debt to GDP, the size of the current account deficit, or the level of interest rates. Understanding what has given rise to those imbalances and assessing how and when they might be ‘corrected’ helps guide our assessment of the risk of recession.

Our fate, to quote the bard, lies not in our stars but in ourselves.