A sideways look at economics

In the film-within-a-film ‘Strike’ (from The Comic Strip Presents…), the UK miners’ strike of 1984 is given the Hollywood treatment, with Al Pacino (or, rather, a brilliant Peter Richardson playing Al Pacino) as Arthur Scargill, and Meryl Streep (played by an equally brilliant Jennifer Saunders) as his wife. Scargill is interpreted as brooding and sentimental, with dark undertones of violence, emphasised by his penchant for endlessly cleaning and loading his revolver. His wife is neurotic and icily distant, and prone to obsessively peeling oranges – a failing marriage is the backdrop to the political drama, and somehow the oranges, peeled but uneaten, capture that failure symbolically. The plot unfolds with the Scargills’ seriously ill child staging a miraculous recovery that — the film suggests — springs directly from her father’s passionate, dauntless will, a will that ultimately restores peace to the family home, delivers a victory for the miners, and secures a reversal of government policy to close the mines.

The comedy arises from the incongruity. It’s hard to think of a scenario less suited to Hollywood schmaltz than that brutal and impoverishing dispute, or a character less likely than Arthur Scargill to be played by a Hollywood method actor.

Richardson as Pacino as Scargill

Arthur Scargill

If it sounds absurd, that’s because it was designed to be so.

But there are echoes of that absurdity in real life: witness the recent decision by some staff at the Bank of England to go on strike. The comedy arises from the incongruity. When the film rights to this episode are sold, we can anticipate George Clooney playing Mark Carney, with a smooth-as-espresso aloofness, while downtrodden Bank staff fight for their rights and ultimately triumph, perhaps while simultaneously delivering strong and stable government, a Brexit satisfactory to all sides, and a return to robust productivity growth… or perhaps that’s a step too far?

There is a genuine issue at stake. Real wages have fallen for some years thanks to a salary cap, in place at the Bank of England as it is right across the UK public sector. But even here, the scenario still has comedy value. The MPC has frequently drawn attention to the fact that the evolution of real wages is front and centre in their considerations of when to hike rates. It would be ironic, to say the least, if one of the proximate causes of higher real wages and therefore higher interest rates in the UK were a successful strike at the Bank of England! Imagine the headlines: homeowners to pay for higher wages at the Bank…

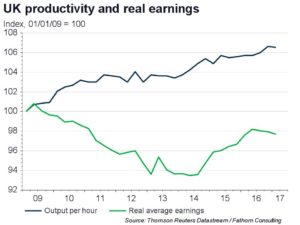

In the long run, the textbook says real wages move in lockstep with productivity. Since the UK’s productivity growth is worse now than it has ever been in the country’s peacetime history, the prospects for real wages are bleak. Any increase over and above the growth of productivity is a strong signal of inflation to come: you can’t change productivity just by paying people more, not at the whole-economy level. That, at any rate, is what the textbook says.

Is the textbook right? There are two reasons to be doubtful.

First, real wages have not moved in line with productivity in the UK since the recession. The labour share of income has fallen here, as it has across most of the developed world. That means the bulk of the gains from improvements in productivity (however small they have been) has been returned to the owners of capital rather than to labour. If real wages were to grow ahead of productivity, the labour share would recover some of its lost ground. Shareholders would suffer as the share of profits would fall. Does that mean general prices would rise faster than before? Not necessarily – firms can only achieve higher prices if the market will bear them, and the global economy that we now inhabit makes that harder than ever.

Second, as we have argued previously, part of the reason why productivity growth is mired in such a weak equilibrium is that ultra-low interest rates stifle the forces of creative destruction. So higher inflation induced by higher real wages could, by moving us away from ultra-low rates, help put productivity growth on a stronger trajectory. If you start from an ultra-low rate equilibrium then you can, perhaps, improve productivity growth by paying people more. This is not an argument about so-called ‘efficiency wages’, which bid up the real wage of those in employment at the expense of creating higher unemployment. It is an argument about the relationship between low interest rates and low productivity growth.

So what would we advise Mark Carney in relation to this strike? Maybe this is a good dispute to lose.