A sideways look at economics

Ever get tired of waiting for Donald Trump to cut taxes, Emmanuel Macron to reform the entire euro area, or to see David Davis take some notes to a Brexit meeting?

With volatility in financial markets at record lows and asset prices at, or close to, record highs, traders seem to be twiddling their thumbs and waiting for the good news to finally arrive. The Bank of England raised rates for the first time in ten years this week, but even the flurry of activity that followed that decision lasted no more than five minutes. Come back again in ten years’ time.

Wouldn’t it be nice to see a little action again? New highs. New lows. Investors scrambling to work out the value of things. Something traders can disagree on from time to time.

Take a bow, Bitcoin.

The recent surge in the price of Bitcoin continues to make even Tulip Mania look chilled. The price is very high, and it’s volatile too: you could have lost your house, and then bought another two houses, by mortgaging and investing in Bitcoin this year.

As an asset Bitcoin is intrinsically worthless. Bitcoin fans will doubtless argue that it’s no different from fiat money in this respect. But that’s to do a disservice to notes and coin, in our view. Notes and coin have government backing. The UK monetary base, for example, is backed by gilts. For every £1 coin in circulation, there’s a matching gilt somewhere in the vaults of the Bank of England. Ah, but a gilt is simply another intrinsically worthless piece of paper, you might say. Maybe, but it’s a promissory note of Her Majesty’s Government which, as we know, has the power to seize assets from any UK resident in the form of taxation. Allegedly, Bitcoin was invented by a bloke called Satoshi Nakamoto, who probably isn’t even really a bloke called Satoshi Nakamoto – but does he carry the same credibility? Bitcoin may be a useful means of exchange because hipsters accept his credibility. But what if Satoshi Nakamoto turned out to be someone like, say, Piers Morgan? Would Bitcoin still hold the same level of credibility among its base?

As the most well-known and widely-traded virtual currency, Bitcoin allows users to bypass banks and other payment processes to pay for goods and services directly, without the need for an intermediary. Proponents say this gives it value, along with the blockchain technology it’s built on.

Another tick for Bitcoin, according to its advocates, is that unlike traditional currencies, whose supply is controlled by the central bank via interest rates, the number of Bitcoins in circulation is finite. To be precise, there can physically never be more than 21 million Bitcoins in the system. Currently, the number of Bitcoins in circulation is around 16 million. Bitcoin is trading today at $7400, which would give the company a market capitalisation of $118 billion.

While the theoretical stock of Bitcoin is fixed, the number of new virtual currencies is infinite, meaning lots of new digital currencies with catchy names have sprung up left, right and centre. This has caused an influx of so-called Initial Coin Offerings where programmers can offer new cryptocurrencies for sale in order to attract capital investment, a move that’s recently been banned in China. You’d think increased regulation would cause the price of Bitcoin to fall. You’d be right. It did, but only temporarily. The number of punters (hipsters?) jumping on the bandwagon has helped the price of one Bitcoin smash through the $7400 mark at the time of writing.

Despite all these new virtual currencies, it’s Bitcoin that manages to dominate the majority of the headlines. Bitcoin is now worth almost six times as much as an ounce of gold. Not bad for a so-called asset that produces no value. To add fuel to the fire, it was announced this week that CME group, the world’s largest derivatives marketplace, would start offering futures contracts on Bitcoin. This will not only help to bring Bitcoin into the financial mainstream, but it’ll add yet more momentum to the already frothy virtual currency market. It may also give traders something to do in their low-volatility boredom.

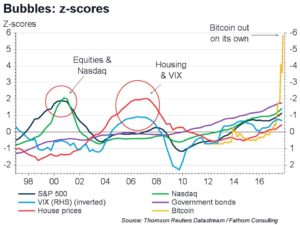

But assuming Bitcoin does have some value, is it in a bubble? To answer this question, we’ve applied the same methodology as we have to value other assets. Our analysis covered the US, Japan, Germany, France and the UK across a number of asset classes (US equities, both the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ, house prices, bonds and finally, Bitcoin). We looked at the magnitude of previous asset price bubbles by converting the series into returns, dividing them, where appropriate, by a relevant denominator, and normalising them into Z scores. We found that prices of most assets relative to nominal GDP are generally very high.

Government bonds and the NASDAQ are nearly two standard deviations above their trend – expensive. Arguably, the tipping point for Bitcoin was back in 2013 – it was in that year that Bitcoin usage, which had grown rapidly up to that point, began to level off as Bitcoin gained widespread acceptance. We’ve used data since then to calculate how many standard deviations its current price is above its long-run average, and the answer is six. Scarcely believable, I know. Using historical precedent as a gauge, ‘bubble territory’ usually begins at around two or maybe three standard deviations above the respective mean of each series. In this case, Bitcoin certainly fits this criterion, and even goes beyond it based on recent data.

But interestingly, these bubbles are all set against a backdrop of sanguine financial markets and eerily low volatility. Risk metrics are at, or close to, all-time lows. The VIX is at an all-time low, sovereign yield spreads and corporate bond spreads are also close to all-time lows. This is ominously reminiscent of the run-up to the great recession back in 2008.

We don’t expect asset prices to come crashing back down to earth imminently. But with Bitcoin, there are a number of risks that could result in a sharp price level correction. Should Bitcoin be stripped of its near-anonymity, it would be hard to justify its current price, particularly if governments decide to intervene, whether in the form of regulation or even creating their own digital currencies. The ‘always ahead of the curve’ Swedish Riksbank has been toying with the idea of so-called e-kronas that would give the general public access to a digital accompaniment to cash underwritten by the state. It’s still early days, but definitely something to keep an eye on.

However, what we do know is that historically when the private sector has innovated, the state has usually stepped in to regulate. And it’s hard to visualise a world where Bitcoin manages to avoid reverting to its long-term average at some point down the line.