A sideways look at economics

Everyone loves a surprise, right? Be that in the form of a rare win at the bookies, an unexpected Christmas present, a surprise party or even just a chance encounter with an old acquaintance. There are occasions, however, when surprises are bad. Do I want my car to break down? No. Do I want it to rain when I’ve left my umbrella at home? No. Do I want my forecasts to be wrong? No…

As George Box once famously quipped, “all models are wrong.” If anyone comes to you and tells you that their model is right all of the time, they are either wrong or they are lying (sometimes they’ll be doing both!). A model is by definition a simplification of the world and therefore cannot explain all that happens. In other words, forecasts will yield uncertainty and, by extension, subsequent outturns will ‘surprise’ from time-to-time. As economists, we have to live with that uncertainty to a degree, although we are always trying to find ways to minimise it. A good model can therefore be thought of as one that helps to either reduce the likelihood of surprises or shrink the magnitude of those surprises when they do occur.

The type of model I consider to be really bad is one that makes the same mistakes time and again. As the US economist and Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson once said, “When my information changes, I alter my conclusions.” Models (and economists) that don’t do this tend to repeat their own errors. As laid out in a previous TFiF, one cause of this might be the sunk cost fallacy, whereby individuals erroneously stick to a losing position due to the amount of time, effort and reputation they have previously invested in it. Alternatively, they might simply not be paying attention to the model’s performance.

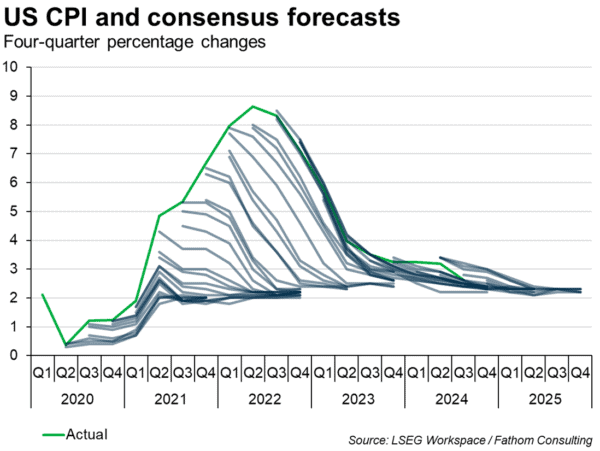

Let’s look at a recent example of this — US inflation forecasts. As you can see in the chart below, between March 2020 and June 2022 the consensus of economists (as polled by Reuters) consistently predicted that inflation would swiftly return to target. Each month, inflation continued to surprise consensus to the upside, and each month the polls continued to suggest that inflation would soon start to fall. This continued on for two years… (I’ll point out here that Fathom’s prediction was for inflation to be much, much stickier than others expected — you can even date this back to March 2020.) My take on this is that many forecasting models failed to account for the effect of dislodged inflation expectations on CPI outturns.

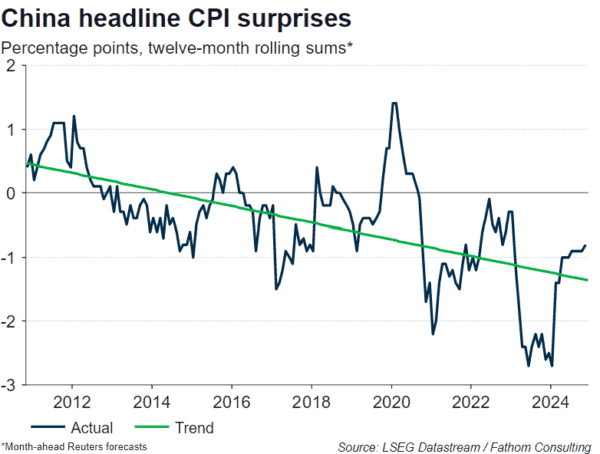

Another example of persistent forecast errors can be seen in short-term Chinese inflation forecasts. Looking at the Reuters poll once again, you can see that the consensus of economists is typically too bullish on their month-ahead inflation projections for the PRC. What is more, those forecast errors are generally increasing over time! In China’s case, forecasters’ projections seem to me to have failed to account for the weakness in China’s domestic demand and the persistent impact that this can have on inflation (excluding food and energy, CPI has been hovering around the 0.5% mark over the past two years or so).

Of course, these are just a couple of very glaring examples of forecasters failing to adapt their model to reflect new information. There are clearly others, and I’m sure that I too can occasionally be accused of repeated mistakes. However, I’m always somewhat sceptical when I come across examples of persistent forecast errors such as these and, when I see the outturns differ from the polls, I find myself asking: “Is it really a surprise?”

More by this author