A sideways look at economics

“Something’s coming. I can feel it, and it’s coming right around the corner at me, Squadron Leader!” Hilts (Steve McQueen), The Great Escape.

For small companies to retain their independence, they need two things: to make profits, and to grow. But the growth part of that is in expectation: it’s important to see beyond current vicissitudes (whether positive or negative) to what growth is likely to be in years to come. Whether you’ve had a good year or a bad year, treat those two imposters just the same and focus on looking ahead. It’s hard to do that, speaking as an owner of a small business: sometimes very hard.

The same applies to inflation-targeting central banks. They must see beyond current fluctuations to what inflation is likely to be in the medium term.

Owners of small businesses and central bankers alike are always looking for easy rules of thumb — for generalisations, so we can avoid the difficult work of having to think about this particular occasion. But, in general, there are none.

Does a good year last year matter for our business strategy? Yes. What does it mean for strategy? It depends.

Does the current inflation rate matter for the medium-term outlook? Yes. In what direction? It depends!

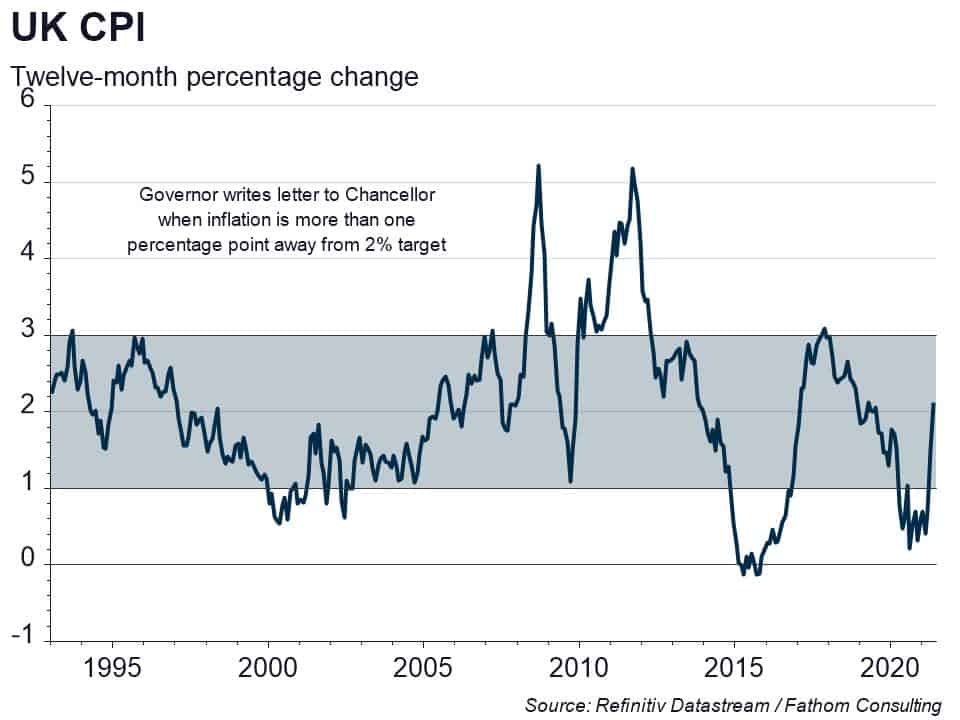

In the UK, inflation-targeting was introduced in 1993, the year after sterling was ejected from the exchange rate mechanism of the euro. Since then, inflation has overshot its target significantly on two, or perhaps three, occasions. The first was in 2008/09 as a result of high oil prices and a collapse in the value of sterling prior to the Great Financial Crisis — oil reached $150 per barrel and sterling depreciated by around 25%. The second followed increases in VAT introduced by George Osborne. And the modest overshoot in 2017 reflected the further collapse in sterling that occurred after the Brexit referendum in June 2016.

On each occasion, the medium-term impact of the initial price-level shock was deflationary. Higher oil prices tended to push up the general price level and, by doing so, reduced real incomes and real profits. The consequence of lower real incomes was lower real aggregate demand. And the impact of that was to reduce inflation down the line.

The same applies to a one-off depreciation in the currency or to an increase in indirect taxation: the price level rises; aggregate demand falls; inflation falls in expectation.

Nice — so now we can generalise, surely? We’ve got three clear examples since we started inflation-targeting of inflation overshooting by enough to trigger a letter from the Governor of the Bank of England to the Chancellor. And each of those examples was deflationary in expectation, so it was appropriate for the MPC to see beyond higher prices and not adjust interest rates. Now here we are again. There’s a risk (acknowledged this week by the Bank) that inflation will push through 3% again — so surely it’s safe to assume there’s nothing to worry about?

Nope.

Agreed, there are base effects in play in the current increase in inflation. Lower oil prices were dragging inflation down previously, but that effect has now washed out of the annual numbers, so inflation is bound to pick up again. Nothing to see there. Similarly, VAT was cut during the pandemic, and pulled inflation down for a year afterwards, an effect that is now coming to an end, so inflation is likely to pick up again. Nothing to see there either.

So far, so close to previous experience.

But what’s new is what has happened to real incomes. In the biggest recession of all time, real incomes for households and for firms increased dramatically, courtesy of massive fiscal stimulus. It’s real incomes that drive aggregate demand in expectation, above all else. They were supported by lower oil prices and by lower VAT too, and that support is washing out of annual growth rates now. But they remain high, and the savings that have been accrued over the last year are exceptionally high. Growth is already strong and is increasing in expectation. Aggregate demand is likely to go through its pre-pandemic level in coming months and may well exceed its pre-pandemic trend shortly after that.

These factors point to higher inflation in expectation.

Does that mean that interest rates should rise? The Bank is likely to say no to that, reasoning that it’s too early to be sure that inflation is higher in expectation; past experience suggests caution. In our opinion, that argument is incorrect. There are different factors in play this time.

But Fathom would also argue that interest rates should stay put for now. In fact, higher inflation should be accommodated, even welcomed; and then embedded, by setting a higher inflation target down the line. This will help in three ways. First, it will allow for deeper negative real interest rates in the face of any future recessionary threat. Second, it will help unwind the excessive debt burden on both the public and private sectors of the economy. And third, it will lead to a higher degree of creative ‘churn’ in steady state, supporting the productivity growth that is the holy grail of macroeconomic policy. In short, we might just have been offered the chance to break free of the low inflation, low interest, low productivity trap of recent years. Could this be the Bank’s great escape?

Further reading:

- ‘GEMO 2021 Q3: Inflation – deal with it, or roll with it?’: https://www.fathom-consulting.com/research-notes/gemo-2021-q3-inflation-deal-with-it-or-roll-with-it/ (7 June 2021)

- ‘Will central banks adopt higher inflation targets?’: https://www.fathom-consulting.com/research-notes/will-central-banks-adopt-higher-inflation-targets/ (12 July 2019)