A sideways look at economics

‘Best of’ lists and summaries of the past year… Twitter is full of them. Instagram is full of them. Even the news is full of them. To keep up with the trend, it’s only fair that the first TFiF of 2020 is a look back at of some the best blog posts written by Fathomites in 2019.

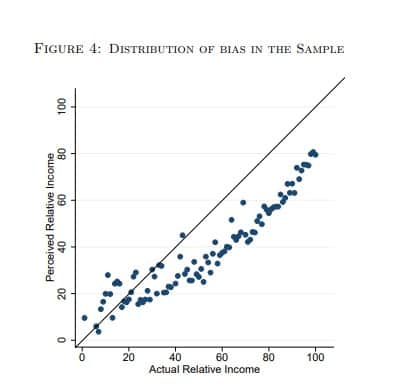

Let’s start with social media. In ‘Social media, and fear of failing to ‘keep up with the Joneses’’, Joanna Davies talked about how ‘peacocking’, or showing off on social media (luxury holidays, watches, or the perfect family photo after hours of squabbling), may distort readers’ ability to accurately compare themselves to the rest of their social network. A study in Sweden found that almost 70% of survey respondents underestimated their position on the income distribution by over 10 percentage points. Not only does this distortion create inefficiencies at the individual level, but it may also result in sub-optimal government policy. On being informed of their true position, policy preferences moved to the right.

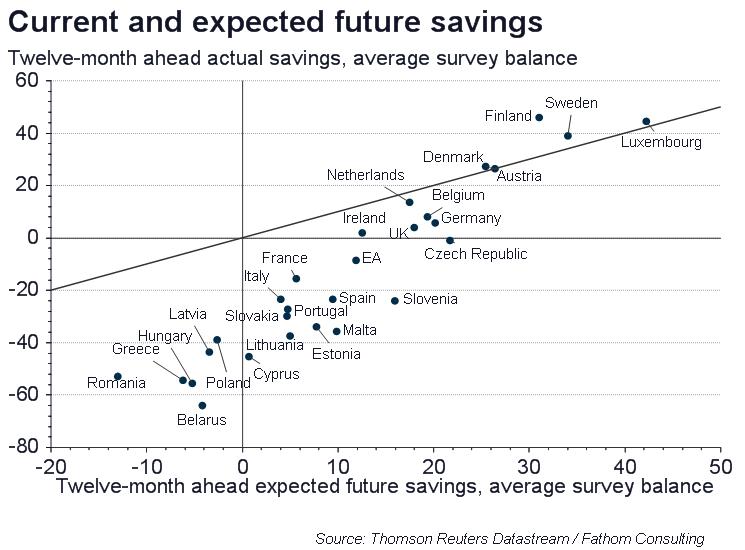

Maybe, then, it makes sense to cut down your social media activity. It might even be your New Year’s resolution. In which case, don’t go to Tobias Sturmhoefel looking for motivation. His scepticism is based on the fact that one of the most popular commitments is to improve one’s financial health, despite individuals in most countries consistently overestimating their future savings. The excessive optimism is not limited to New Year’s resolutions but is a year-round phenomenon. In ‘Don’t expect much from your New Year’s resolutions’, he used the European Commission’s monthly consumer survey to produce the chart below. Taking the analysis further, he then showed that countries with higher expected increases in household savings tend to be unhappier than those with lower expectations. The lesson to be learned here may be that excessive and persistent optimism about something which is unlikely to change isn’t the way to achieve happiness and self-improvement.

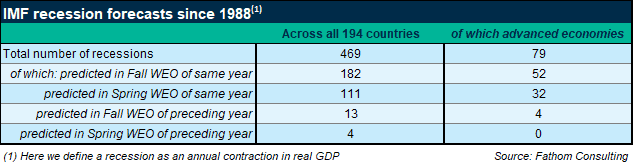

Speaking of self-improvement, one of our more widely quoted TFiFs (it was even cited by Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller in his book Narrative Economics) was ‘The economist who cried wolf?’ by Andrew Brigden, our Chief Economist. He worked out that the IMF has only foreseen, in the spring of the year before, an annual contraction of real GDP in 4 out of 469 instances since 1988. Of course, recessions are rarely a result of a gradual slowdown turning into a technical recession — they are non-linear events. It’s not easy to see them coming, but there’s clearly scope for improvement.

A new strand in our TFiFs looks at climate change. In ‘Economists are warming up to climate change’, Florian Baier provided a neat summary of how economic models will have to evolve to incorporate environmental externalities. They will have to capture the interaction between economic activity and global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and how policy measures affect this relationship. They would also have to describe how emissions of CO2 influence its concentration in the atmosphere, and how that relates to the time path for global temperature. Finally, to close the circle, a model would need to link changes in temperature to economic losses. Not only environmental disasters such as hurricanes and fires, but also how agriculture would adjust to changing temperature, changing consumer behaviour, etc. We’re not the only ones thinking about this. Having run two G7 central banks, Mark Carney has now been tasked by the UN to help bring climate-related risks into the heart of financial decision-making. However, if it was running experience the UN was after, my colleague Kevin Loane would have been a better bet.

So, what’s in store for 2020? It would be unwise to commit myself and my colleagues to particular themes, but — to hold us all to account – expect more of the same. That is, the application of rigorous economics to either often-overlooked topics or aspects of daily life, with the occasional oddball. Happy New Year from Fathom!