A sideways look at economics

Penalty shootouts have haunted English football fans for years. Since 1990, England have been involved in nine shootouts across the European Championship and World Cup competitions and won only two of them: a dismal record for what is supposed to be a premier footballing nation. An estimated 31 million people in the UK tuned in to watch England play Italy in the Euros final of 2021, only for the team’s journey to be ended by the all-too-familiar nemesis. So with English hopes high once more in the 2024 Euros, which start today, I thought I’d take a shot at trying to solve penalties from an economics perspective, hoping to uncover how the team can improve its chances.

When broken down and simplified a bit, penalties inherently contain many properties which are used in game theory;

- A penalty is a two-person game: a shooter and a goalkeeper

- The game is simultaneous: both players must decide at the same time which direction to take (the taker to shoot and the keeper to dive); the ball takes on average around 0.3 seconds to cross the line once it has been kicked, so the keeper doesn’t usually have time to wait for the striker’s decision before making their own

- The game is one-shot

- It is a two-outcome game: goal and no goal

- And finally, the game is zero-sum; the gain to one party is achieved directly to the detriment of the other

To maximise their chances in a game with these characteristics, each player must attempt to find the mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium.[1] A strategy called ‘minimax’, coined by the mathematician John von Neumann, can be implemented when trying to ‘solve’ a zero-sum game of this type. The minimax strategy aims to minimise the possible loss that a player could face, which in a situation with two outcomes is the same as maximising their possible gain. To accomplish this, each player must somewhat randomise the direction they take.

Evidence suggests that professional footballers have been successfully applying the minimax strategy since as early as the mid-1990s. Palacios-Huerta (2003) analysed a dataset of 1417 penalties from 1995-2000, and found that both kickers and goalkeepers were able to successfully generate random sequences of left and right, switching the side they chose neither too often nor too little.

Additionally, Palacios-Huerta found that both parties favoured the kickers’ ‘natural’ side at frequencies very closely matching those predicted by perfect game-theory strategy. For right-footed kickers, this natural side is to shoot to their left (or down the middle), where they can strike the ball with more power and precision; and the opposite for left-footers. Game theory dictates that both parties should choose their natural side more frequently than their weaker side. This is because the kicker, with more control and accuracy on their preferred side, is more likely to score if the goalkeeper dives in the same direction, and is also less likely to miss the target.

Based on the dataset, Palacios-Huerta found that the mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium dictates that kickers should have shot to their non-natural side 41.99% of the time, and in reality they did so 42.31% of the time. Similarly, he found that goalkeepers should have dived to that side 38.54% of the time, and they did so 39.98%. Therefore, both parties performed remarkably close to the optimal game theory equilibrium.

As technology has improved, analytics have become integral to every aspect of football, including penalties. It is now commonplace to see notes scribbled on a goalie’s water bottle, indicating which side the analysts think they should dive based on each taker’s previous penalties. Similarly, the taker will be informed about the goalkeeper’s preferred diving direction and their dominant hand, to identify their stronger side. This means that applying a minimax strategy is more important than ever, with both parties having close to perfect information.

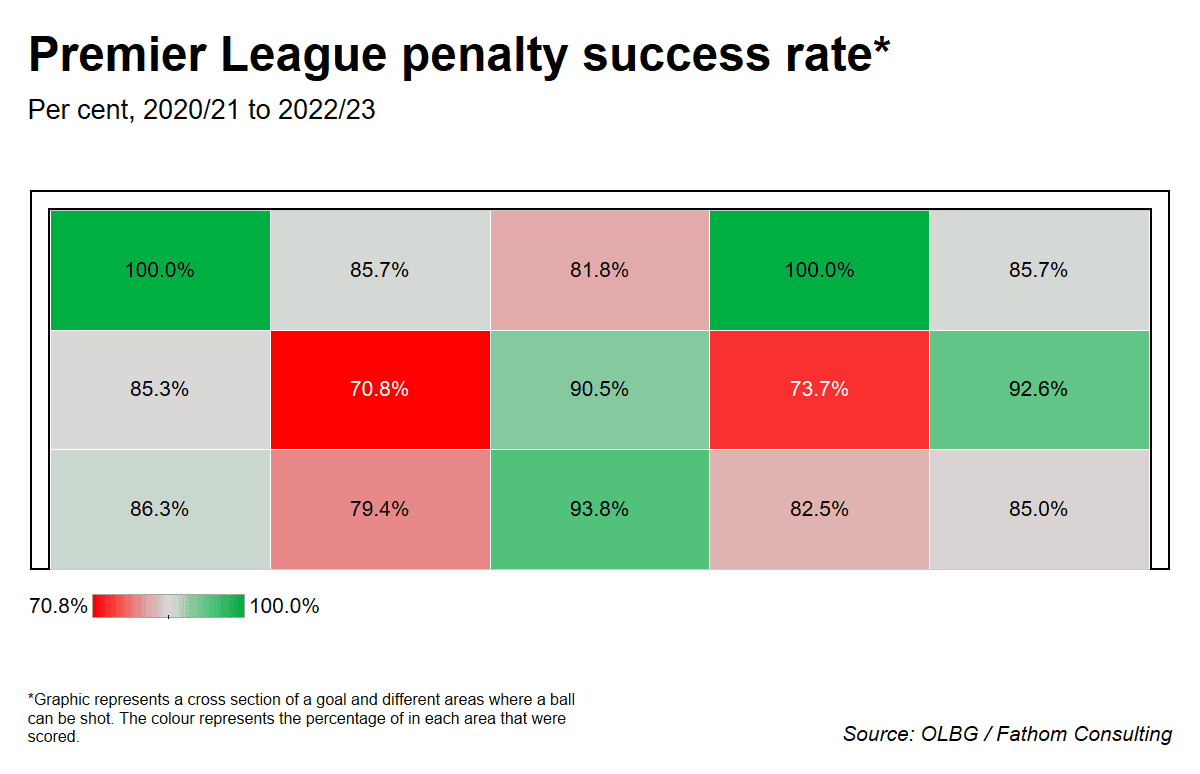

Palacios-Huerta’s analysis focuses on which side the players choose, but height is also an important factor in penalty-taking, and here we see that players may not always make the optimal choice. Penalty takers almost always aim for the lower part of the goal, with 91% of penalties taken between the 2020/21 and 2022/23 Premier League seasons targeting the bottom two-thirds.[2] However, during this period, zero penalties aimed at the top third were saved, making on-target shots to this area almost guaranteed goals, as goalkeepers very rarely dive high. If this is the case, why don’t penalty takers aim for the top corner more often? This would result in more goals scored in the short-term and would benefit penalty takers in the long run, as goalkeepers would need to adjust their strategies and dive high more often to cover this – thereby increasing the chances of takers choosing a different spot to the goalkeeper and scoring. Surely professional footballers, who dedicate their lives to the sport, are able to find the top section of the goal pretty easily with a dead ball from 12 yards away, especially those who are the primary penalty taker for their club or country?

One reason for this puzzling omission is that players may not necessarily choose the decision which optimises their outcome, but rather perform within the limits of what others expect of them. How often do you hear fans and commentators alike screaming ‘just hit the target’ or to ‘shoot low and hard’? A taker whose penalty is off-target is usually berated, even if they’ve aimed for the top corner, which may be the option which maximises their chance of scoring. On the other hand, when an on-target penalty is saved, the focus tends to be on the keeper as the ‘hero’, unless fans consider the penalty was particularly poorly struck.

As a football fan, I get the feeling that penalties which are shot down the centre of the goal and saved by the goalkeeper are seen to fit into this ‘particularly poor’ category. Data suggest that the middle portion of the goal is actually the safest to shoot in, so players also do not shoot down the middle often enough – quite possibly because of this phenomenon.

This thinking also applies to goalkeepers, who may dive to the sides too often to avoid criticism. Emiliano Martinez, Argentina’s keeper and hero of the penalty shootout that settled the 2022 World Cup final, said in an interview: “I said to Paulo [Dybala]; if I save the first [penalty], the next one has to go down the middle. That’s when it comes, my psychology training for years. You know why? The pressure is on the other goalie. So he’s going to dive. We don’t want to look stupid in a World Cup final standing in the middle.”

And sure enough, in the World Cup final, after Martinez saved Coman’s penalty to give Argentina the advantage, Dybala calmly shot the next penalty down the middle, and Lloris went flying to his right. After the match, Paulo Dybala said “I was going to go for the [right] side, the goalkeeper dove to that side, but I heard what [Martinez] said. I changed at the last minute.” Dybala’s penalty may have been saved or he may have missed if he had stuck to his original decision, but he listened to Martinez, kicked it down the middle and scored. Argentina went on to win the shootout and lift the World Cup.

Of course, players cannot shoot every penalty down the middle, as goalkeepers would pretty quickly clock on and remain standing there. But this option appears to be underrepresented in most players’ mixed strategies.

Many players also attempt to use other tactics to disrupt the game theory and tilt the odds in their favour. One study found that when a player celebrates scoring their penalty, their opponent is more likely to miss the next one, and a two-handed celebration increases these chances!

So, what’s my advice to any English lads who may have to step up in a penalty shootout over the next month? Ideally, if you’re feeling confident (and have practised), aim high. If not, apply minimax and randomise, but don’t be scared to go down the middle. Either way, after putting the ball in the back of the net, go wild!

[1] A ‘mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium’ is a game state in which no player can increase their payoff by playing an alternate strategy (choosing to ‘go’ in one particular direction more often)

[2] https://eplindex.com/107323/premier-league-penalties-data-unlocks-scoring-secrets.html

More from Thank Fathom it’s Friday