A sideways look at economics

In the classic 1924 cornerstone of modern social science, The Gift, the French sociologist Marcel Mauss formally distinguished for the first time a gift from other types of consumer behaviour to which they are inexorably linked. Economic theory says that a good should bring utility to a consumer and have an intrinsic value that can be used as a means of exchange. Mauss argued that a gift adds reciprocity as an important third social dimension. Gifts provide a link between people built and renewed on an implicit bond of trust and distance within socially prescribed bounds as “the [gifted] objects are never completely separated from the men who exchange them”.

Gifts and presents are terms used interchangeably, yet the latter clearly stresses a personal dimension. Through presents we underscore our presence and the commitment to renew a mutual bond of shared experiences through time. (The origin of the word ‘present’ is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, Middle English: from Old French, originally in the phrase mettre une chose en present à quelqu’un ‘put a thing into the presence of a person’.) Yet, with the festive season upon us, it’s hard not to notice how gifts have lost their timeless and physical dimension becoming an increasingly impersonal and contrived exercise. We hardly ever gift our presence any longer and the loop of giving and receiving seems woefully unbalanced. I’m not narrow-mindedly suggesting that giving has been reduced to an inconvenient side effect of receiving. True, there are some gifts where we might catch a whiff of ulterior motive, or where the giving and receiving lines might be a bit blurred. Like the friend who bought a romantic weekend getaway to Rome for his girlfriend together with a dozen of his mates during a six-nations rugby game, on Valentine’s Day. This was a ballsy call that actually paid off as she admired his confidence, saw the practical side and had a field day in the shops of Rome.

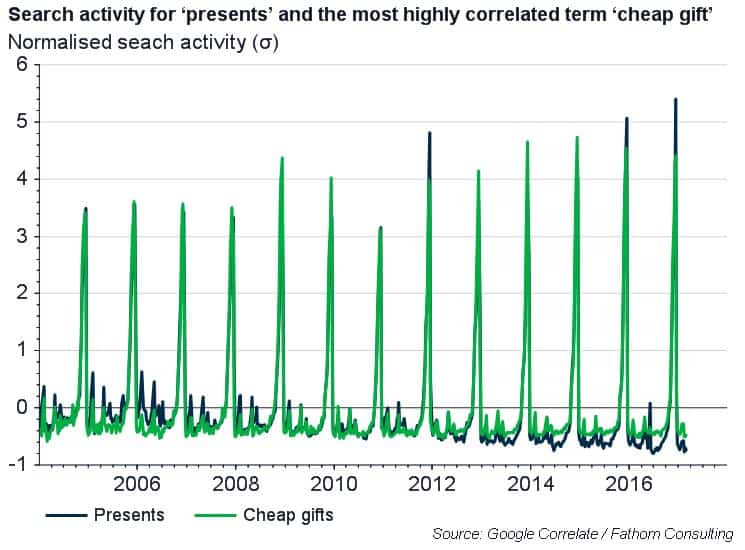

The point I’m making is that very few of the gifts that we exchange at Christmas conform to Mauss’s description of an almost magical link between the material and the spiritual through a mutual presence and experience. I think this is because the individuality of the gift has been devalued by a spiral of ever more uniform and predictable material expectations and virtual connections. It’s particularly revealing that the search activity for ‘presents’ should be most correlated with that of ‘cheap gifts’ (0.9689) with clear seasonal peaks around Christmas according to Google correlate. I rest my case.

Actually, I don’t. Anyone who, like me, has largely procrastinated on his gift list, should resist the urge to get suckered into the usual waltz this Christmas. The preachy advice would be a call for us all to be more present with our presents. A more pragmatic approach and less orthodox way would be to resort to playing Secret Santa. Let me explain, as there are various upsides to doing so.

First, the chance of pleasing someone ought to be much higher since expectations are very low to begin with. Second, if done properly, it can be hilarious and memorable. Two friends used to throw Christmas parties in their Brick Lane flat B.H. (that is Before Hipsters in archaeological London dating conventions) that are enshrined in the stuff of legend thanks not in small part to the Secret Santa dynamics. (I appreciate that I’m being vague, but details are best not gone into on the record.) Secret Santa also offers valuable opportunities for self-introspection. Take the example of the less than friendly colleague who was given a 3L tank of antifreeze, or a friend’s ex-wife being gifted this book by a somewhat prescient Secret Santa. It also allows you to impress people without being accused of brown-nosing. In a previous job, I got my own 15 minutes of fame at the court of the sultan-like CEO as his PA urged me to reveal myself as the Secret Santa of a hilarious and clever present to another colleague. Finally, Secret Santa is made to deemphasise the gift and focus on the ‘whodunnit’ element of the game within a group of people. This is much closer in spirit than mainstream practice to Mauss’s idea of gifts as dynamic social contracts. In other words, Secret Santa presents allow us to reassert our presence through playful anonymity and emphasise the value of shared experiences, physical social interaction and memories. With this, I wish you all happy Secret Santa as I’m off to buy my £10 cheap gift, ahem, present!