A sideways look at economics

Here’s a bit of Friday afternoon trivia for you:

ATLANTA FALCONS: 2017 SUPER BOWL CHAMPIONS

#Fakenews news headline from an Atlanta-based news organisation or slogan emblazoned on the T-shirt of an African villager?

It’s the African villager, of course.

The Atlanta Falcons are not the 2017 NFL Champions – they lost to the New England Patriots 34-28 in the final earlier this year, despite leading that match by 28 points to 3 at one point. One cruel reminder of their team’s epic collapse is a video clip of someone hurriedly removing merchandise proclaiming the Falcons winners from a shop floor.

It’s not uncommon for American sports teams to print hundreds, if not thousands, of T-shirts and other memorabilia crowning them Champions before they even take to the field. In the glitzy world of American sports, teams insist on having such items instantly available for fans to purchase after a title-deciding game. The problem is: one side always loses.

Little is ever said about the losers’ pre-printed kit, which is swiftly banished from American soil, and sent to Africa, never to be seen again. A corporate relations officer of a major charity explained: “Where these items go, the people don’t have electricity or running water. They wouldn’t know who won the Super Bowl. They wouldn’t even know about football.”

Fair enough. It’s better for the environment for these clothes to be recycled than to end up in landfill. People in Africa need clothes. And Africans don’t give two hoots about American football. Are these gentlemen really bothered that the Chicago Bears were not actually the 2007 Super Bowl winners?

But sending second-hand clothes (SHC) to African countries has become a contentious issue. Some charities give clothes directly to those in need, but most clothing donations in rich countries end up being sold, for profit, in developing nations. The trade in SHC is a multimillion-dollar global business.

The East African Community (EAC) – a trading bloc consisting of Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda, Burundi, Tanzania and South Sudan – has had enough, and last year it proposed to ban the import of all SHC from 2019, claiming that it was undermining their local textile industries.

And these countries may have a point: several academic surveys have concluded that rising SHC imports have resulted in a decline in local apparel production in African countries. Kenya, after all, once had a large textile manufacturing industry and it used to ban the import of SHC.

This author has some sympathy with this point of view, perhaps, because I myself grew up in Africa. As a self-respecting economist, I do believe in the benefits of free markets and trade, but I also recognise that since developing economies are at a different stage of their economic development, they do, at times, need to take measures to protect their fledgling industries.

Besides, isn’t this an example of Western countries dumping their excess supply on emerging markets?

It also turns out that one of the groups most opposed to the ban is US workers in the SHC sorting business, which employs an estimated 40,000 people. Lobby groups are pushing the US government to take retaliatory measures against some East African countries.

That’s right – American workers are worried about losing their jobs if poor Africans stop accepting their used clothes. Further proof, were it needed, that the world has gone mad!

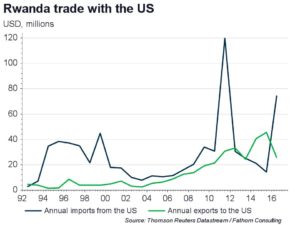

Despite the US Trade Representative reviewing Rwanda’s eligibility to continue receiving duty-free access to US markets, Rwandan President Paul Kagame is determined to press ahead with the ban on SHC. Given the trade deficit that Rwanda runs with the US, perhaps he isn’t too worried about losing access to US markets.

Mad world or not, after further investigation and some deep pondering, it turns out that there are at least six reasons to believe that the proposed ban by the EAC might not really be such a good idea.

First, many people in East African countries want to buy SHC, which incidentally has a name in many African languages: mitumba, in Swahili, or salaula, in Bemba, the native language of Zambia. Many Africans like the variety of these SHC imports. They also like the price.

Second, trade in SHC also creates jobs for Africans: thousands of street traders buy and sell these goods, earning a living in the process. Cleaning and sorting of SHC clothes on arrival from the West also creates jobs for Africans.

Third, the West isn’t dumping SHC on Africa – it has a genuine comparative advantage in generating second-hand clothes.

Fourth, there are environmental benefits from re-selling second-hand clothes, instead of dumping them into landfills.

Fifth, African governments receive a lot of tax revenue from SHC imports.

Sixth, banning SHC isn’t a prerequisite for success. Other developing countries, like Pakistan, have successful textile export businesses despite importing massive amounts of SHC.

African countries do need to take protective measures to foster local industries. But it’s fundamental that they take measures that will eventually allow them to become internationally competitive. Kenya banned SHC imports for many years, but its domestic textile industry was never able to stand on its own two feet; as soon as the ban was lifted, the local textile industry went into decline.

There are many things that East African countries could do to support their local industries, such as building better infrastructure, improving the rule of law, clamping down on corruption, investing in education and attracting foreign direct investment.

Rwanda is already doing these things and has become one of the fastest growing economies in Africa as a result, admittedly from a very low base. Banning imported SHC could tarnish its image among international investors and do more to hinder, than help, its economy. Kenya has said it won’t be part of the planned ban on SHC – Rwanda might consider doing the same.