A sideways look at economics

April was a time for reflection, or rather, one of those periods when one reflects about time. As the Fathom off-site drew to a close on a sunny Bilbao afternoon, and I lay on a park bench, slightly tender from the night before and in dire need of caffeine, time stood still as if bowing to an overload of contentment and inner peace. Ok, I had simply dozed off after an overindulgent couple of days, but there was more to it than that. It dawned on me that life was good and I was happy.

The beautiful thing about happiness is that it makes the untangling of cause and effect a redundant exercise; a happy state feels like a game of Tetris where the pieces happen to fall in the right place. The triviality of cause and effect can only happen in a timeless dimension. Indeed, bliss is said to be eternal.

The link between time and happiness has always been something I found fascinating. Long before grasping the physics of time and space, I was lucky to be exposed to the idea that time represents a subjective state specifically associated with changes in mental stimuli. I vividly remember sitting in bed reading the final paragraph of Erasmus’s In praise of Folly as a teenager (and yes, I also had a life, thanks for the concern). I was captured by the author’s provocative assertion that truly happy people ought to be in a state of madness with no awareness of time and space.[1] At times, I’ve perhaps tried to take Folly’s life coaching a bit too literally, particularly heeding her parting remarks of “I hate a man that remembers what he hears. Wherefore farewell, clap your hands, live and drink lustily, my most excellent disciples of Folly”.

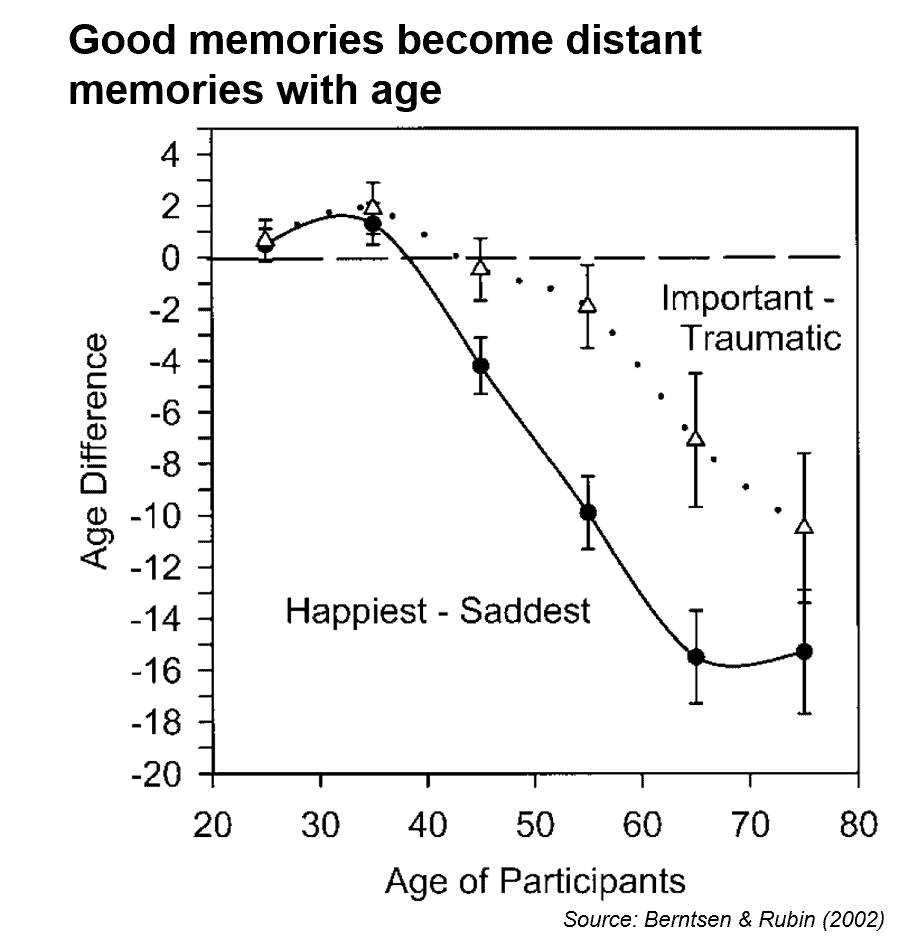

Disappointingly perhaps for Folly, I got progressively more interested in how experimental and behavioural psychology treats the perception of time, its interaction with different types of stimuli and the role of happiness. On happiness, an interesting paper showed how happy memories, particularly those forged in one’s 20s, tend to be an indelible feature of our lives, while the unhappy or traumatic memories tend to fade much more quickly over time. The paper also shows some clear and somewhat worrying age trends for someone, like yours truly, on the cusp of his 40 landmark. The chart below demonstrates how, as people get older, the age of the happiest memory tends to drift ever further back in time relative to the saddest event.

Thankfully, experimental psychology also provides a recipe to help mitigate this gloomy, yet rational reality. Enter the oddball effect, a tried and tested phenomenon that demonstrates how breaking a routine with a new stimulus inflates its perceived duration relative to a repeated one. The trick is to flood the brain with new information that it hasn’t processed before thus triggering the perception that time has slowed relative to a benchmark life routine.

There are two forces that prevent the oddball trick being a slum-dunk option. First, new information can be either happy or sad, what matters is only that it is different enough. The uncertainty associated with new experiences and risk aversion act as disincentives to proactively seeking out routine-busting experiences. Second, the older we get the more difficult it becomes to trick the brain with new experiences. This latter phenomenon is simply a function of a younger brain having processed less information relative to an older one. In fact, the brain’s perception of a fixed unit of time can be proxied by the square root of the age of the person.[2] This means that a year of life and experiences for my 7-year-old son is equivalent to 2.4 years of my life experiences and 3 years of my dad’s, whilst an extra year of my life is only worth an extra 3 months of experiences relative to my father.

At first glance, younger people appear to have it exceptionally easy: they tend to be happier and their lives flow more slowly. However, this is true only from the perspective of an older self and his accumulated memories. In other words, young people might not fully appreciate the advantages of youth until they are much older. This subtlety has deep implications. As we saw, the gap in age between the happiest and saddest memory grows more negative with age, but the actual perception of this gap might not be so negative. For a 60-year-old, the happy memories of his 20s will have been perceived as happening at a significantly slower pace and therefore as having lasted longer relative to more recent, sadder events. It’s not time that heals, but happiness through the dilation of time.

The life hacks from the above are twofold. First, have as much fun as possible in your early years, but, unlike Folly’s advice, make sure you can remember most of it. Second, as you age, use the accumulated happy memories as a spur to embrace and seek out life’s oddballs to make further happy memories, slow time and lengthen life. Indeed, the idea that eternal life may be sought through new experiences and adventure is deeply embedded in timeless myths such as the Holy Grail or the quest for the fountain of eternal youth. Somehow, I can’t see Indiana Jones summoning the Holy Grail through his favourite takeaway service from the comfort of his sofa.

As for me, whilst I lay on a Bilbao park bench and time dilated in contemplation of my happy state, the realisation dawned on me that I had found my professional Holy Grail in Fathom. A guaranteed lifelong supply of oddballs through always stimulating work, interesting debates and smart colleagues. All this with the moral obligation, as one of the older staff members, to show the younger bright minds of Fathom the importance of always pursuing happiness and a bit of folly.

[1] “And when they come to themselves, tell you they know not where they have been […] and only know this, as it were in a mist or dream, that they were the most happy while they were so out of their wits. And therefore they are sorry they are come to themselves again and desire nothing more than this kind of madness, to be perpetually mad. And this is a small taste of that future happiness”.

[2] This is similar to how market volatility is assumed to grow over time, one for another post.