A sideways look at economics

“QE…works in practice but it doesn’t work in theory”

Ben Bernanke

If you ask people what Quantitative Easing does, you’ll get a list of answers as large as the Fed’s balance sheet. For many, it seems, the purchase of assets by central banks can be used to explain whatever their bugbear happens to be. Inequality? Overvalued stock markets? Inflation? Elevated house prices? Currency wars? Actual wars? Commodity price rises? At different points, all of the above have been pointed to as having been driven by QE. But I’d argue that’s not fair. Rather than being the cause of all the world’s problems, QE seems to me to be a symptom — a consequence of low equilibrium interest rates.

Inflation

Inflation was the original fear about QE. The historian Niall Ferguson led the charge, warning after QE programmes were launched that the inevitable result was going to be high inflation. Animated proponents of this view pointed to places such as Zimbabwe and eras like the Weimar Republic as possible signs of how this would all end. They conveniently ignored Japan, where QE had been done since 2001 with no signs of inflation. In the end, despite extended periods of QE throughout the 2010s, the big problem was seen to be that inflation ended up being too low rather than too high.

I can hear some of you thinking: But Kevin, we now have high levels of inflation after having done QE! Dear reader, I cannot dispute this. And many people point to ‘money-printing’ as a primary cause behind the current bout of inflation. However, this argument feels flat to me. We had a decade of tight fiscal alongside QE (and no pandemic or major Russian war) without any material inflation. And we now have a period of high inflation following ultra-loose fiscal and QE (and a pandemic and a major Russian war). Unless QE operates with enormous lags, it seems most likely that it was ultra-loose fiscal, the pandemic and the major Russian war that were the primary factors behind the current elevated CPI readings.[1]

Some might argue that QE was a pre-requisite to enable the levels of borrowing seen during the COVID period. That’s not something that can be proven. But in my view, the experience of Japan suggests that the market would have facilitated that level of borrowing for DMs with their own currencies and independent central banks, even without concurrent QE programmes.

Interest rates

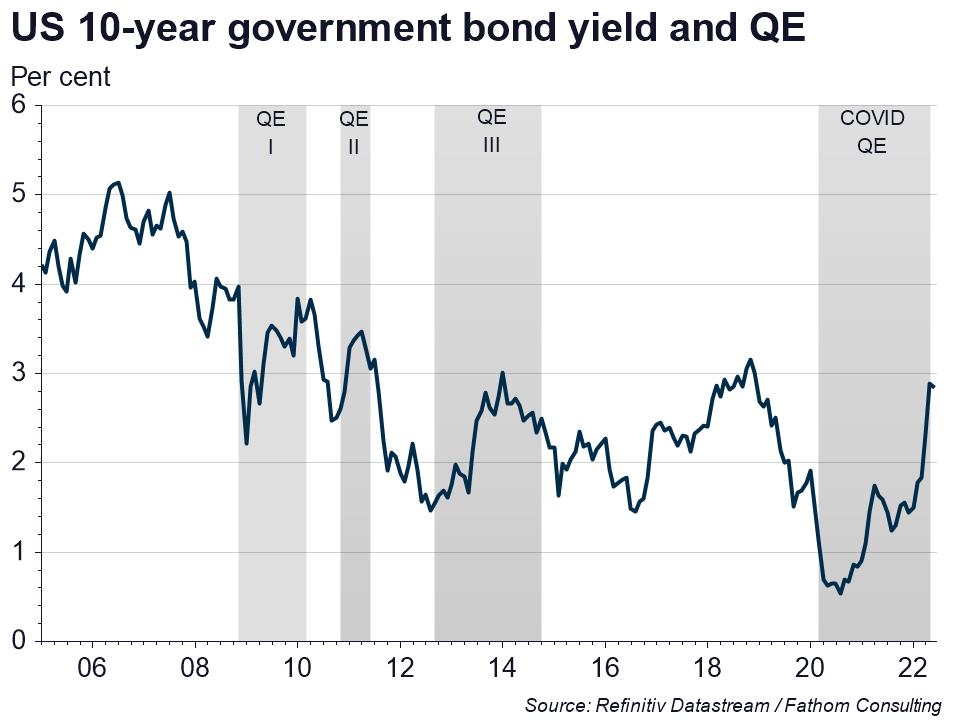

After the original fears of rampant inflation failed to materialise, QE sceptics moved on to criticise it for keeping interest rates “artificially low”. Most wanted interest rates to be higher and saw QE as part of the problem. Lowering long-term interest rates is indeed the primary reason given by policymakers for QE, and there are several papers that “prove” it does this. However, even central bank staff admit that there are huge issues with the event studies that tend to be the method used to underpin this finding.[2] I’d argue that QE’s bigger impact is that it signals where we are in the cycle, and therefore where long interest rates are likely to be headed moving forward.

QE programmes tend to be launched during periods of crisis. When crises happens (as in 2009), QE does seem to play a critical role in ensuring proper market functioning, including via the provision of liquidity. As practiced in steady state, however, QE seems to be mostly a signal of where you are in the cycle. Soon after it’s launched: bottoming out to early stage (when rates are more likely to rise). Soon after it ends: topping out and late stage (when rates are more likely to fall). These factors seem to me to be more important than QE in determining interest rate moves, and help to explain the uncomfortable truth that periods of QE often seem to coincide with rising long-term yields, while periods without QE are usually associated with falling long-term yields – the opposite of what policymakers say it achieves. (Yes: counterfactuals. I know. Still.)

Asset prices

I reckon quite a few people could go along with me up to now, but this next idea may be a step too far. Among those who think QE doesn’t do much, many would probably still agree that it “artificially boosts asset prices”. Whether it’s Crypto, WeWork, Argentinian debt or two-beds in zone 2: the popular view is that the price of all of these has been artificially boosted by QE. If it were true that QE artificially lowered long-term interest rates, then that would be a decent argument. However, it seems far more likely that an extended period of low short-term interest rates (topic for a future blog) was the bigger cause of (previously low) long-term interest rates and various asset price booms.

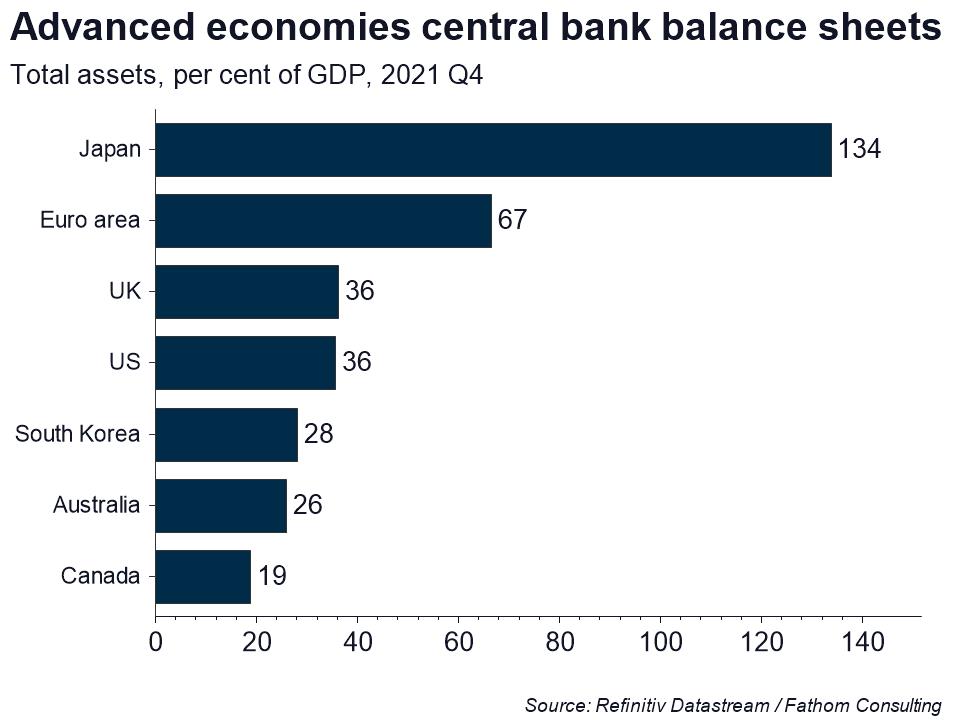

If QE really were the source of asset price bubbles, then it would make sense for bubbles to be biggest in those countries that have done the most QE. However, that’s not the case. When scaled to GDP, Japan has the largest QE programme, followed by the euro area (although the ECB balance sheet is not as accurate a proxy for QE in the euro area as it is elsewhere). Yet European and Japanese house prices are not widely seen as being bubbly, and something similar is true for their equity markets. Meanwhile, Canada and Australia, two countries with extremely elevated house prices, have done comparatively little QE. Most people have US QE in mind when they think about price booms, and maybe there is something particular about US QE that drives global bubbles.. The US hosts the world’s reserve currency, so it’s possible. However, it seems more likely there is something unique about the American economy that produces world-leading companies that make its stock market trade at higher multiples.

I have acknowledged that QE has a big impact at times of crisis. And it could be argued that the euro area, without fiscal union, is at permanent risk of crisis. Moreover, the exchange of an ECB reserve (backed by Germany) for a BTP (backed by Italy) is not exchanging one safe asset for another. In that sense, QE actually does a lot in the euro area. However, perma-QE, which it seems is where the currency bloc is heading, may end up eroding the ECB’s credibility as an inflation-fighting central bank, perhaps lifting long-term inflation expectations as a result. Were that to happen, you could argue that QE does actually boost prices after all.

[1] One caveat is that the Fed’s desire not to raise interest rates before ending QE, and not to end QE without giving ample warning, probably delayed its first interest rate increase. This is more of an issue with the Fed’s forward guidance than with QE itself.

[2] https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/third-quarter-2017/quantitative-easing-how-well-does-this-tool-work