A sideways look at economics

Here is a science experiment you can do right now from the comfort of your home/office. Go find yourself a mirror, a small one held at arm’s length will do fine. Look into the reflection of your left eye. Holding the rest of your head still, now glance at your right eye. Now left. Then right. Notice anything? Apart from the fact that you look great today (keep up the good work), there is something else. You will never be able to see your eyes in motion. You should be able to feel your eyes moving but you will never see it. However, someone watching you do this will be able to see your eyes move.

This is an example of the phenomenon of chronostasis. The most famous example of this being the stopped clock illusion, where if you glance at a clock with a ticking second hand or digit, that first second appears to take longer to tick over to the next than any other. Your eyes do actually see a blur of motion, similar to if you shake a camera around. But when processing that information, the brain cuts out that period of blur and replaces that with whatever it sees next. This is known as saccadic masking.

Out of interest, this is only possible if what you perceive to be ‘now’ is actually ever so slightly in the past, accounting for the brain’s processing delay. And further out of interest, because the brain is waiting for signals from the whole of your body (including your toes), the taller you are the longer that delay is. Can you tell yet that I’m fun at dinner parties? No?

At this point you could rightly point out to me that this is supposed to be an economics blog. But perceptions are very important to so many things in we care about at Fathom. And those perceptions do not always match up with reality.

Earlier this week, in an In brief I discussed how households’ perceptions of inflation are often perfectly mirrored in their expectations for future inflation at all time horizons, even if (counter to reality) they believe that prices are rising at greater than 10% annually. This may be rational if households believe that some of the factors driving deviations of inflation outturns from target will persist into the future. But, when this gets dangerous for central banks is when households expecting prices to rise in the future may take those expectations into wage discussions to protect their own real wage, driving further persistence. This is where wage-price spirals threaten to emerge.

And turning to geopolitics, governments (particularly democracies) must worry about how the general population perceive their actions if they want to stay in office. Which brings me nicely onto a discussion about COP26. As the UN climate conference comes to a close, it remains up in the air how people will react to the decisions and agreements (if any) that result from the two weeks of negotiations. For everyone there is a bottom line, and for democratic governments what matters is whether the people care enough to make the issue of climate a vote changer come the next election.

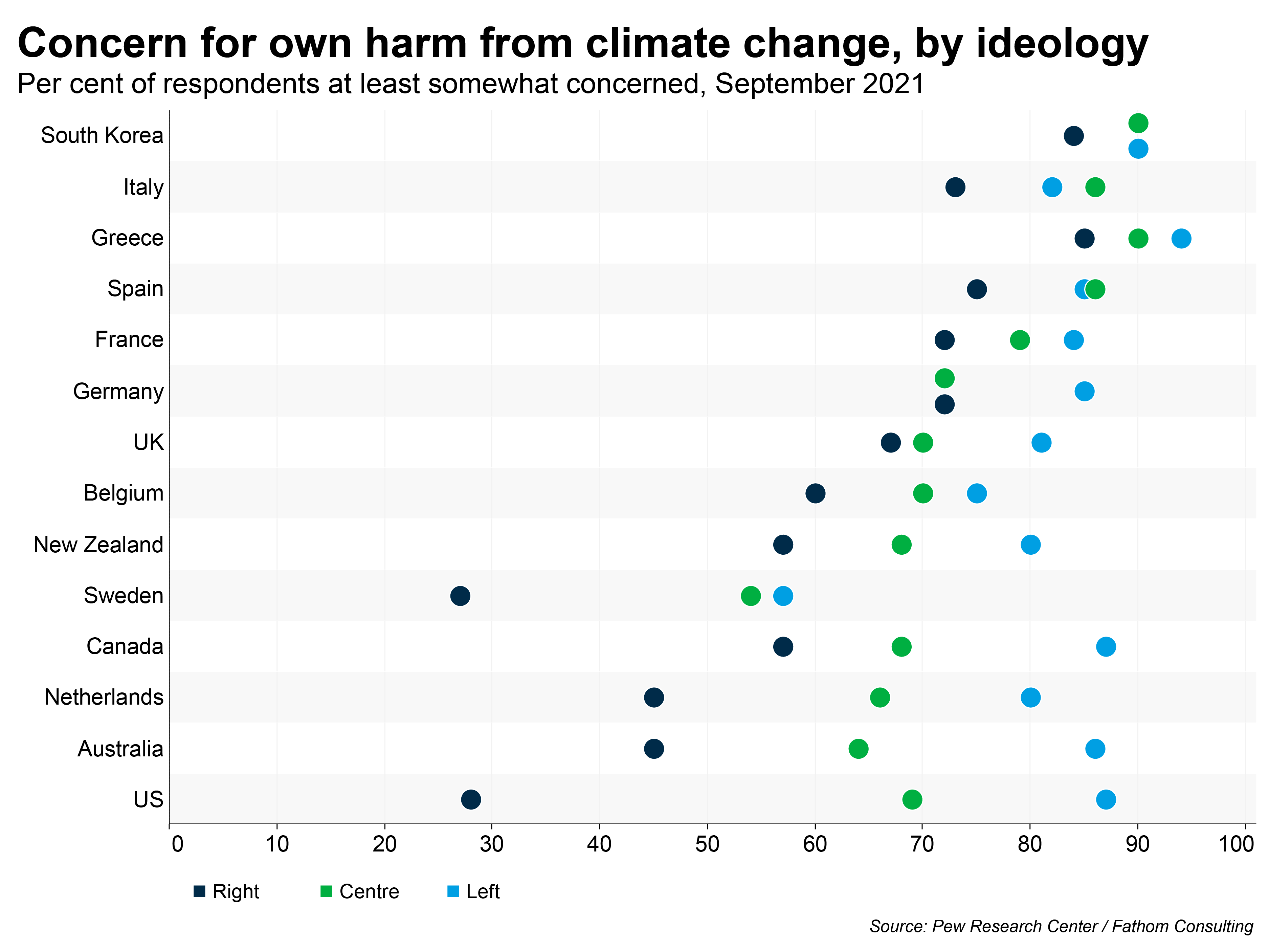

And the degree to which climate change is a) an important issue and b) highly politicised varies by country. A survey by the Pew Research Center, chart above, shows the lowest personal concern about climate change among Swedes, Australians and Americans. And the largest variation by political ideology in the US and Australia. No wonder we’re seeing more climate action from the Biden administration compared to under Trump, and more climate reluctance from Morrison’s centre-right Liberal Party of Australia.

Some of this perception will be self-perpetuating, i.e. my government is not concerned by climate change, so I shouldn’t be, so the government does not see it as a major issue etc. And breaking that cycle for those climate sceptics would be a major success for COP26. Our Head of Climate Economics, Brian, noted this week that parts of his experience of the first week at COP felt like preaching to the already converted. Outside COP, this surely will need to change.

Climate science is pointing to a reality of warming temperatures, more frequent extreme weather events and rising sea levels unless swift action is taken. That has been broadly acknowledged by the draft agreement published on Wednesday this week. That agreement received a mixed reception on how far the measures included would reduce climate change, and (at the time of writing) remains unsigned and subject to change. Some world leaders at the negotiating table may deem any agreement a success, while activists, climate campaigners and the leaders of small island nations will be pushing for more much more action. Who wins that argument in the eyes of the public will probably be the defining factor of how much action there is in future climate policy of some of the major GHG emitters.