A sideways look at economics

Interest in the monetary statistics is something that comes and goes. For most economists, it’s something that has now largely gone. Their heyday to date, during my time at least, came in the 1980s. In April 1980, UK chancellor Geoffrey Howe launched a ‘Medium-Term Financial Strategy’ (MTFS), which included target ranges for the rate of growth of the money supply. The objective of monetary policy at the time was to meet those targets, and so began what has become known as ‘the UK monetarist experiment’ of Margaret Thatcher’s first government. To help policymakers, the Bank of England published a whole smorgasbord of money supply measures, and for a time these data were perhaps given greater prominence even than GDP or inflation itself.[1]

As a guide to policy, the MTFS was found wanting within a matter of months, when the official interest rate was cut by a percentage point, despite measures of monetary growth being above their target range. The reason is that, as politicians clearly recognised but money supply measures seemingly did not, the UK was entering a deep recession. Using language very much of the time, John Biffin, a Treasury minister and committed monetarist, was later reported to have a described one measure of the money supply as a ‘wayward mistress’. Economists simply knew too little about the relationship between measures of money and things that mattered, like growth and inflation, to use them as a guide to policy.[2] Monetary targeting was abandoned in 1987, in favour of exchange rate targeting, which led subsequently to ERM membership. And this proved to be a roaring success.

One of the difficulties economists have with money is that it’s very hard to find a role for it — in theory. What I mean by this is that theoretical models of how the economy works struggle to include it. Fiat money, of the kind produced by central banks around the world, has no intrinsic value.[3] So why accept it as a form of payment? The reason, perhaps, is that you believe it will still have value tomorrow. And the shopkeeper that you visit tomorrow will indeed accept it as a means of payment, because she believes it will continue to have value the day after that. And so on. The difficulty with this approach is that, if you believe at some point far into the future you will be unable to exchange fiat money for goods and services, because (say) the world has ended, then its value very quickly unravels. Economists soon tired of trying to solve this problem, and so many add it in to their economic models simply by imposing a so-called ‘cash in advance’ constraint — a way of saying that cash is needed to buy some proportion of all goods and services because…that’s just how it is.

So what is money anyway? According to the textbooks, money must fulfil two roles. It must be both a ‘medium of exchange’ and a ‘unit of account’. But in order to be effective as a medium of exchange, it must also act as a ‘store of value’. In reality, there are a whole range of assets that have some degree of ‘moneyness’ about them. Economists tend to position them along a ‘spectrum of liquidity’; along a line in other words, ranging from narrow definitions (with notes and coin the narrowest) at one end, through to much broader definitions, including time deposits held at banks, at the other. From my experience, most economists who put weight on the money numbers, tend to have their own preferred measure — either ‘narrow’ or ‘broad’.

Those who look carefully at narrow measures of money might be troubled by the recent substantial expansion of the Bank of England’s balance sheet. As we argued in a recent Fathom the Forecast, by offering to buy up more or less all of the extra gilt issuance likely to be necessary as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bank of England is engaging in ‘monetary financing’. In simple terms, it is using newly created central bank money to finance government spending.[4] As a result, central bank money — one of the narrowest measures of the money supply — is likely to increase by some 40% over the next year or so. Should we be worried by this? No! By using central bank money to finance government spending, policymakers have avoided a potential sharp upward spike in gilt yields, which would have threatened economic stability, and put considerable downward pressure on inflation.

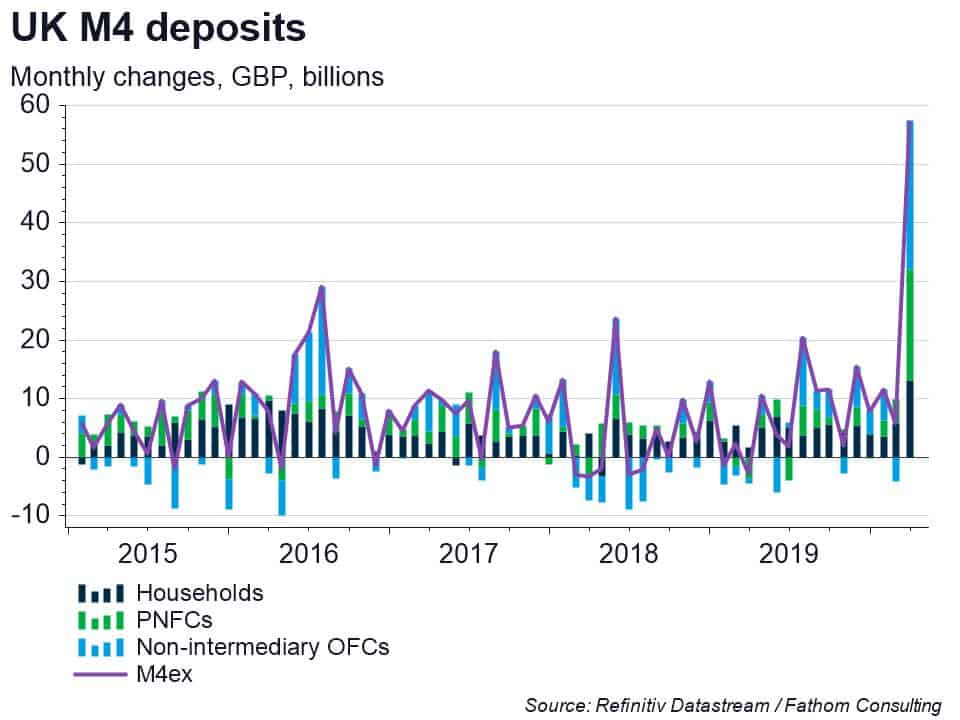

The UK’s headline measure of money — a broad measure — is known as M4ex. In addition to notes and coin held by the UK resident private sector, it also includes their sterling deposits held at UK banks and building societies, minus the sterling deposits of intermediate OFCs (financial corporations that behave a bit like banks) — hence the ’ex’.[5] Like many other economic statistics, M4ex has responded dramatically to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data released last week showed that in March M4ex rose by £57.4 billion, easily the largest increase on record. The increase was also the largest on record across all three sectors: households, private non-financial corporations (PNFCs), and financial corporations (excluding intermediate OFCs). What does this mean? In the absence of additional information, it can be hard to interpret broad measures of money. A sharp increase in bank deposits can be a sign of imminent strength (assets have been converted into liquid form, and are about to be spent), or imminent weakness (unwilling to spend, firms and households are undertaking precautionary savings).

Of course, we do have additional information, and the sharp pickup in M4ex is relatively easy to interpret in the present circumstances. That makes these data more valuable than usual. Banks and building societies create deposits by simultaneously undertaking lending. There’s a counterpart to M4ex known as M4Lex, or M4 lending excluding lending to intermediate OFCs. Changes in M4ex are matched very closely by changes in M4Lex.[6] Looking at the M4Lex data, borrowing from banks and building societies was also very strong, and particularly borrowing by PNFCs, much more so than borrowing by households. Within PNFCs, there were very sharp increases in borrowing by firms operating in those sectors — such as transport, and hotels and restaurants — that one might imagine would have been most severely affected by the shutdown. A likely explanation for the unprecedented expansion of commercial bank balance sheets in March is that banks and building societies were doing their job. They were intermediating between those households fortunate enough still to be receiving an income, and yet unable to spend it in the normal way, and those firms who were undergoing severe financial difficulties.

The monetary statistics have fallen out of favour in recent years. After letting us down on many occasions, they’re not getting quite the attention that they used to. But we’re living in unprecedented times now. With so much uncertainty at present, and in comparison to other measures of economic activity, the monetary statistics have the attraction of being timely, and accurate. The Bank of England keeps a pretty close eye on the quantity of notes and coin in circulation. And all banks and building societies operating in the UK are obliged to provide the Bank of England with a detailed return setting out both sides of their balance sheet. Rather than being based on a survey, the monetary statistics are closer to a census. At Fathom, we’ll be watching the monetary statistics much more closely than usual over the coming months. Though we may not trouble you with them again in future editions of Thank Fathom its Friday!

[1] The names included M0, M1, nibM1, M2, M3, £M3, PSL 1 and PSL 2. When I sat my A-level Economics exam, I could even have told you what they all were.

[2] Some of the historical details in the opening two paragraphs of this blog are taken from ‘British Monetary Targets, 1976 to 1987: A view from the fourth floor of the Bank of England’, by Anthony Hotson.

[3] In my wallet, which had previously remained unopened for a number of weeks, I have just discovered a Bank of England £5 note. On the front of that note it says: “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of five pounds”. I believe it is still possible, in more normal times at least, for a member of the public to take a £5 note to the cash desk at the Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, at which point the cashier will give you…another £5 note.

[4] In the UK, central bank money (sometimes called ‘high-powered money’) is physical notes and coin in circulation outside the Bank of England, plus central bank reserves — electronic money held by commercial banks on deposit at the Bank of England.

[5] For more detail, the interested reader is referred to the following Bank of England explanatory note: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/details/further-details-about-m4-excluding-intermediate-other-financial-corporations-data.

[6]Differences can reflect, among other things, transactions between the public sector and UK banks and building societies, and between overseas residents and UK banks and building societies, as well as foreign currency transactions.