A sideways look at economics

As an economist, Arthur Okun undoubtedly had a talent for making the extremely obvious seem just that. His two most famous contributions to the field are prime examples of this. Indeed, it was Arthur Okun who took two indicators (inflation and unemployment), combined them, and created the Misery Index. Hardly groundbreaking, but it’s still in common use today. Likewise, the eponymous Okun’s Law, which simply regresses changes in the unemployment rate on economic growth, remains a mainstay of 21st-century macroeconomics, albeit a controversial one.

So, what is Okun’s Law, and why is it controversial? Well, for a start, it’s not a law. It’s not even a theory. In fact, it’s probably best described as an empirical rule of thumb. It simply concludes that for every additional percentage point increase in quarterly GDP growth, the unemployment rate will fall by a further 0.3 percentage points.[1] It’s a nice succinct result[2] that’s stood the test of time. So, why all the controversy?

The good

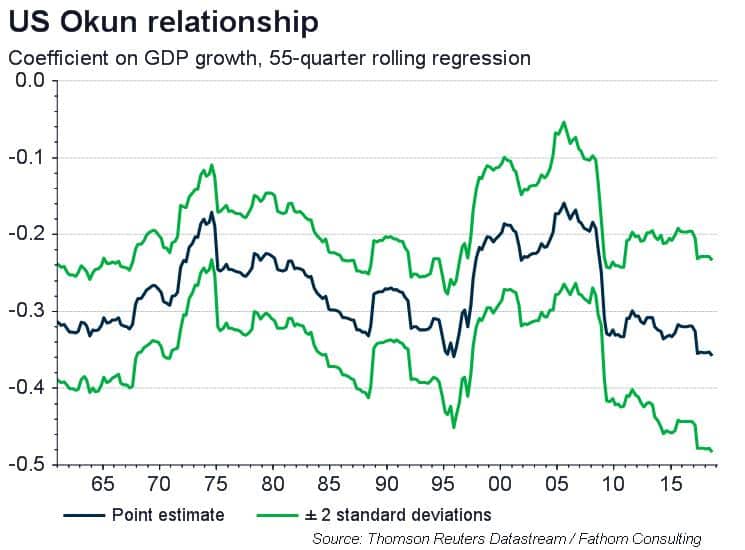

Let’s begin with the good. When you’re trying to assess the merits of any economic model, the starting point must be whether it works. And, let’s be honest, Okun’s Law does work. Indeed, the -0.3 coefficient that was estimated back in 1962 still holds true today. True, it has varied over time, but not by much ― at its weakest, the ‘Okun Coefficient’ briefly fell below -0.2 but it has, on average, remained close to the original estimate and the relationship has always remained statistically significant.

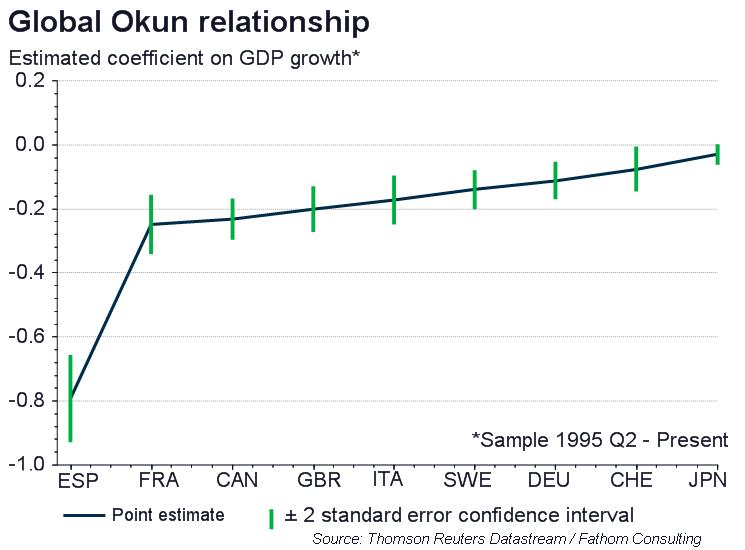

What’s more, Okun’s Law appears to exist in many other countries and, though the strength of the relationship does vary, its stability over time often does not. Indeed, of the nine countries shown below, only in Japan ― a country with a persistently low unemployment rate ― does the relationship not hold.

The Bad

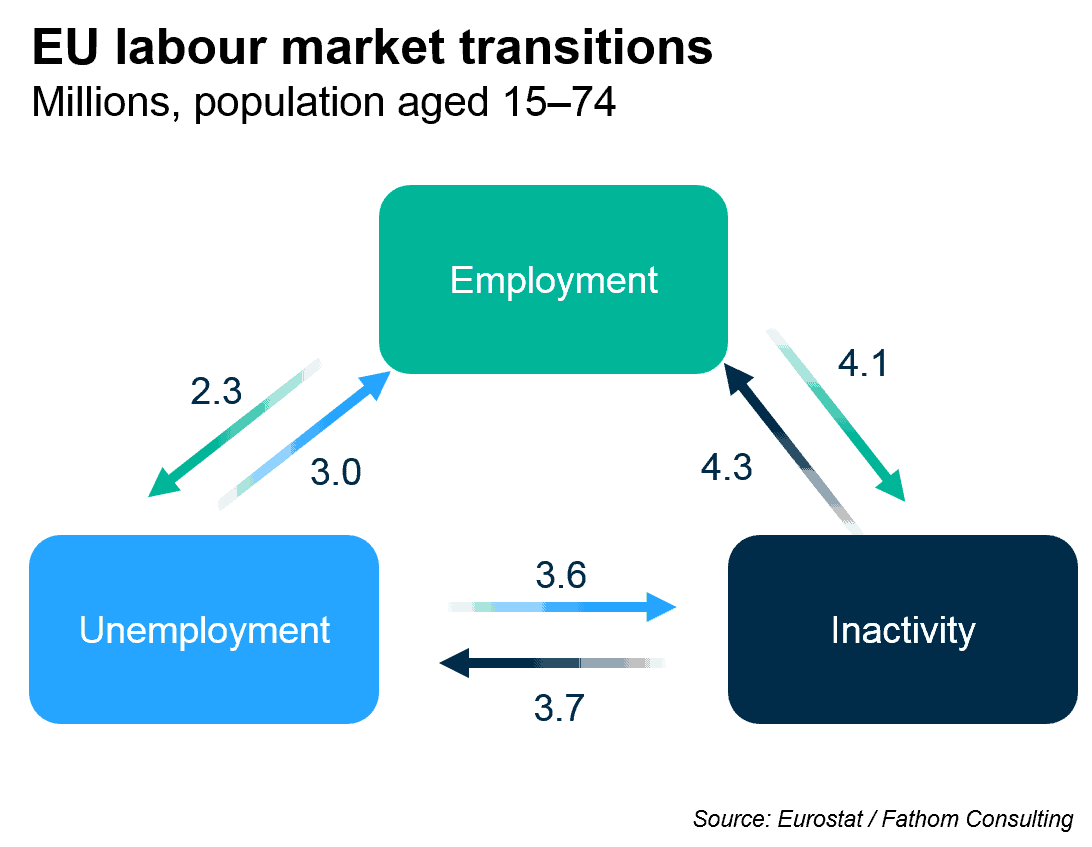

So, why the criticism? Well, for one, theory would probably tell you that the relationship between employment and GDP should be stronger than the relationship between economic activity and unemployment. Indeed, a direct relationship between growth and unemployment would only exist if increased demand for labour was filled exclusively from the pool of unemployed workers and not from those economically inactive. As illustrated in the chart below, this assumption clearly doesn’t hold ― in the third quarter of 2018, flows between economic inactivity and employment than exceeded those between unemployment and inactivity.

The ugly

The real problem with regressing unemployment on GDP is that it suffers from what economists refer to as endogeneity. A word to strike fear in the mind of any economist, the presence of endogeneity implies that the Okun Coefficient will be biased (i.e. not equal to its true value) by additional information not included within the model.

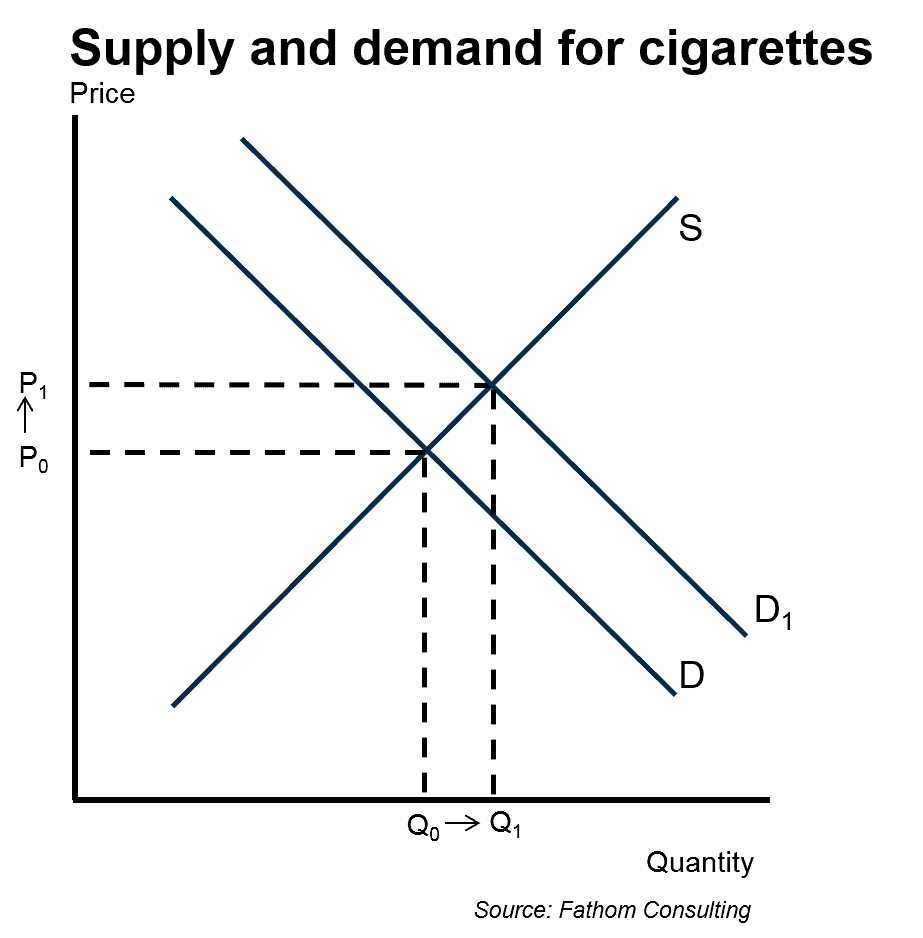

To understand endogeneity better, economics textbooks often use the example of the demand for cigarettes. In this case, a simple regression of the quantity sold on the price may yield a positive relationship between the two, apparently in contradiction of the law of demand. (Rising prices should reduce demand.) However, the true relationship is probably being obscured by the fact that higher prices tend to increase supply. As a result, all that is observed are the prices and quantities at which the market clears. To sketch out the true shape of the demand curve (or the supply curve for that matter), economists often use the technique of instrumental variables.

The same problem is true with Okun’s Law ― it’s likely that both output and unemployment are codetermined. [3] This is the ugly side of the relationship.

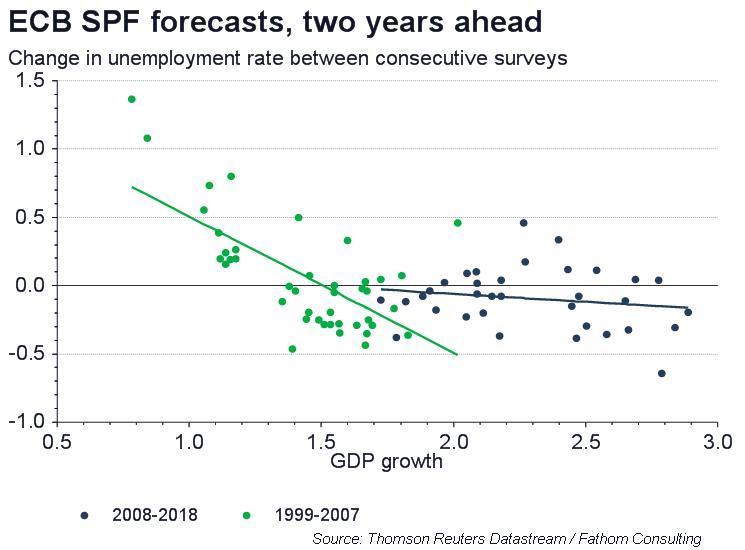

Ordinarily, the presence of endogeneity would be enough for economists to steer clear but in the case of Okun’s Law, this apparently isn’t true. Indeed, evidence from the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) suggests that economists’ use of the relationship has strengthened, not weakened, in recent years.[4] And, it’s easy to see why ― despite its flaws, it does work really, really well. Of course, more complex models might work better, though there’s a certain beauty to parsimony of Okun’s Law. But, should practicality rule over academic rigour? Perhaps.

[1] A.M. Okun, ‘Potential GNP: Its Measurement and Significance’. Proceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section of the American Statistical Association (Vol. 7, 1962), pp. 89-104.

[2] It’s so succinct in fact that the now infamous law is outlined in just two paragraphs. In actual fact, the paper’s primary focus was estimating potential output rather than relating unemployment and growth.

[3] See, for instance, Robert Anderton, Ted Aranki, Boele Bonthuis and Valerie Jarvis, ‘Disaggregating Okun’s law: decomposing the impact of the expenditure components of GDP on euro area unemployment’, ECB Working Paper No. 1747 (2014).

[4] Rupert de Vincent-Humphreys, Ivelina Dimitrova, Elisabeth Falck and Lukas Henkel, ‘Twenty years of the ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters’, ECB Economic Bulletin (1/2019).