A sideways look at economics

Young people in Europe and the US are showing signs of turning against the generation born after World War II . This move can be seen in the meme ‘OK boomer’, which has become a popular online retort to those who are on the wrong side of 50, or who don’t know what a meme is. It’s typically used to dismiss what are perceived to be outdated views on issues such as climate and gender. And while this intergenerational strife has a strong cultural dimension, economics is important too. It would not surprise me if some of today’s students whisper ‘OK boomer’ under their breath during lessons about the strong link between a country’s unemployment rate and its rate of inflation. More fundamentally, economic outcomes seem to be a decisive factor behind this generational split. In many advanced economies, public polling suggests that people believe life will be more difficult for the generation to come. This view is not without foundation. In the US, the percentage of children earning more than their parents has dropped from 90% to 50% in the past 50 years — a trend labelled the ‘Fading American Dream’.

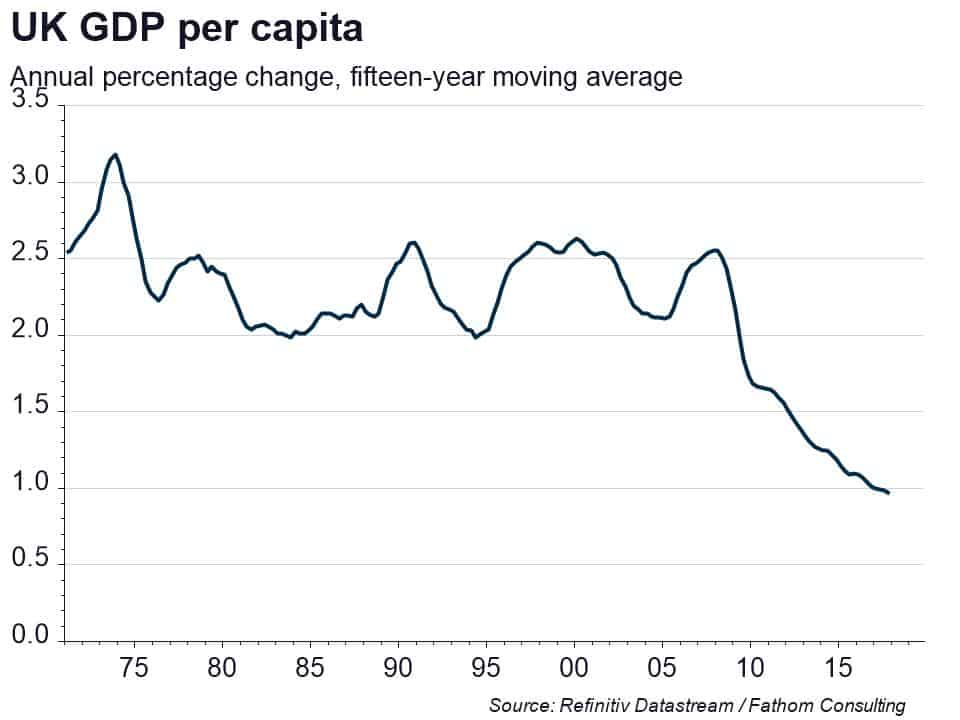

On a range of metrics, the cohort born after WWII in the UK received unique economic tailwinds. Education was free or relatively cheap, and the entry requirements for many professions were often less stringent — so I’ve been told. My dad reports being the sole candidate for his first job. It’s not just income, the returns to assets have also been tremendous. House prices have increased much more rapidly than earnings, aiding those who were on the property ladder earlier, resulting in a large transfer of wealth from one generation to the next. With the future returns on a range of assets expected to be historically low due to current stretched valuations, something similar may be true of bonds and equities. At the same time, many older people think low interest rates are an unfair penalty that artificially reduces the return on their savings, not recognising that having substantial cash savings at all means they’re doing better than most. To top it all off, the annual growth rate in per capita GDP has been drifting down, meaning a reduced rate of improvement in living standards for younger people. Indeed, according to the Resolution Foundation, those born in the late 1980s had lower real earnings in their mid-20s than those born a decade earlier.

It would take a generational radical to blame baby boomers entirely for the current economic woes, but it would be similarly extreme to say that they didn’t benefit disproportionately from the strong conditions that preceded it. It doesn’t seem outlandish to think that they should be leaned on more heavily when governments have to make tough economic choices. However, things seem to have gone the other way. The age at which future generations will be able to retire seems set to go in only one direction: up. Meanwhile, pension benefits for existing retirees are ring-fenced, and wealth is taxed lightly, increasing the burden on the young and those in work. There is a sense that older voters have used their position to secure and solidify their existing economic advantages, a subject discussed in a previous TFiF, and yet still blame the young for perceived failures anyway.

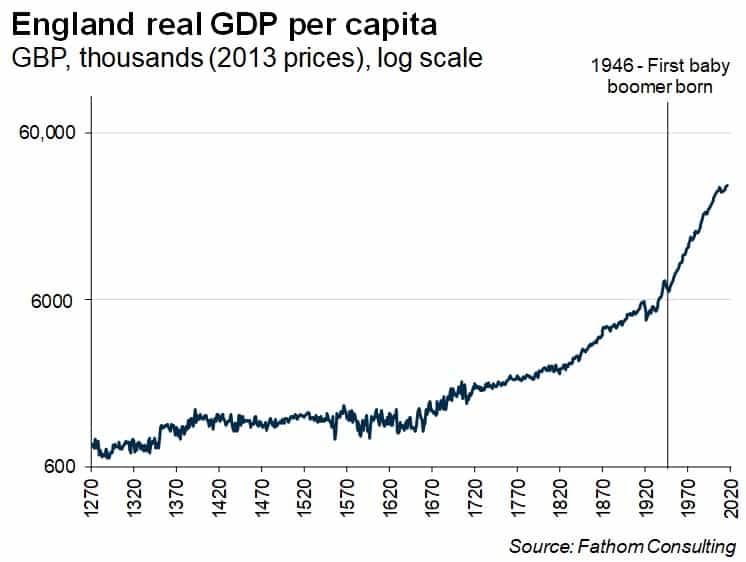

It would be remiss of me not to at least attempt to offer a defence of the current situation. For one, not all baby boomers are rich. There is variation within generations. Moreover, most rich baby boomers will leave something to their kids, calling into question the sustainability of today’s generational solidarity. Some might even question the idea that each generation should expect to enjoy a big increase in living standards over the previous one. From a historical perspective, such progress was rare. It’s fair to assume that living conditions were broadly flat (and bad) for most of human existence. According to the Bank of England, in the four hundred years to 1670, GDP per capita in England increased by 62%. In the less than four hundred years since then, it has increased by more than 2000%. That increase over the past few centuries has been tremendous but is the exception not the norm. All generations born since then, including millennials, benefit as a result. That’s all true, and it’s important to maintain perspective in life. However, when the best thing you can say to a twenty-something warehouse worker is that they should count themselves lucky not to be a medieval serf, all’s not well.

All told, it’s easy to see why many young people would feel hard done by. From an economics perspective, things look bleak. Meanwhile, the generational gap in culture and politics appears to have increased. The ingredients for intergenerational tension are already clear and environmental concerns could make them worse. With that in mind, it seems reasonable to forgive the young for inventing ‘OK boomer’ even though it‘s an unfair characterisation. It has been amusing to see people who previously belittled today’s youth for being too easily offended react angrily to what is, all things considered, a fairly minor put down. More importantly, as far as protests go, a two-word social media post is not exactly Gandhi-like in its ambition. It seems, then, that the bigger question is not why this meme has gained such popularity but why hasn’t there been a more serious and powerful response from the young? It could be that economics is not everything. Life has improved in lots of ways that are not measured in dollars and cents, including, but by no means limited to, entertainment options. Funny Tik-Tok videos, a cynic might say, are the opium of the youth. If that’s true, and nothing much in the way of policy change comes from this, it may be the boomers that end up having the last laugh. OK millennial?