A sideways look at economics

I have not worked a five-day week since April. Yes, really! Between a few days of annual leave and the alarming number of public holidays that we had last month, it’s been a while. But could this amount of leisure soon be the new normal?

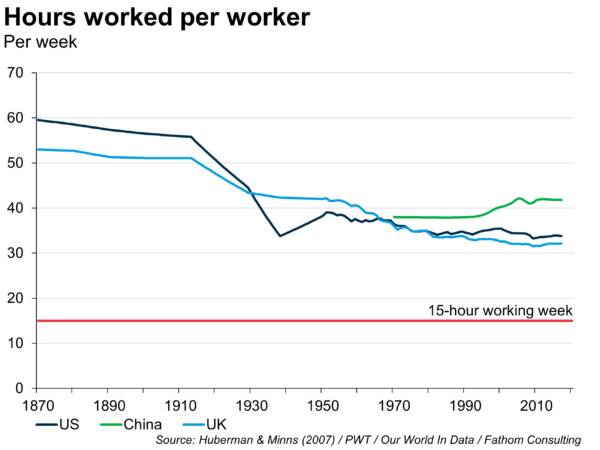

Writing in 1930, John Maynard Keynes famously hypothesised that we could be working 15-hour weeks one hundred years hence. I think he may have got the timing wrong, but we are certainly moving in that direction. Indeed, a chart of the long-run revolution in working hours shows a clear downward trend in both the US and UK.

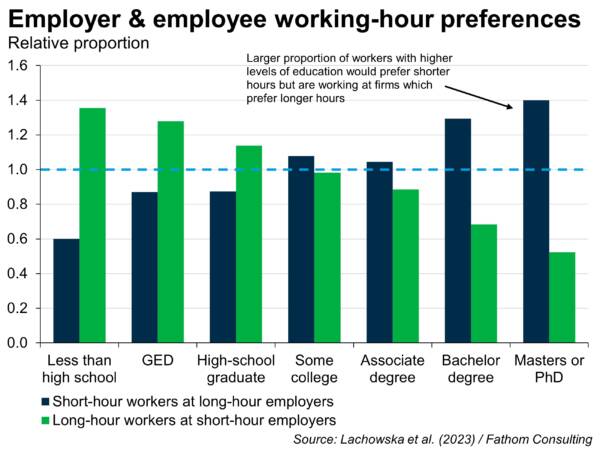

What’s the reason for this trend? Well, as we laid out in Welcome to the machine, our recent report for the Special Competitive Studies Project, when people start to earn more per hour of work, they typically want to work fewer hours and have more leisure time. This is what’s commonly known in microeconomics as the backward-bending labour supply curve. This is not just true over time, but across countries too. Moreover, a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper identified evidence that the connection between higher pay and lower hours also holds true within countries — the chart below shows that the higher a person’s education is (and presumably the higher their hourly wage rates), the more likely they are to prefer shorter working hours. Interestingly, this contrasts with the hopes of employers, who typically desire their more highly educated employees to work proportionally longer hours.

Wages ultimately reflect two things: recognition from employers of the amount of value their workers bring to a firm (i.e., their productivity), and the bargaining power of those workers. Innovation is what drives worker productivity and that trend towards lower working hours — innovation either in the form of developing new technologies or in better harnessing the existing ones. As you will know, the trend in UK productivity growth has been poor in recent years (similar is true in other advanced economies, but the UK has been particularly bad). There are however some signs that productivity might improve in the near future with the advent of new technologies such as artificial intelligence. How much will it boost productivity and wages? And to what extent will it enable employees to voluntarily reduce their working hours and increase their leisure time? Could it even be enough to see Keynes’s prediction fulfilled by the end of the decade?

There’s lots of talk about technology replacing jobs, but is it possible that technology could it actually facilitate a high-income, low-work society? Let’s hope so!

More by this author

An economist’s guide to rocket science