A sideways look at economics

This week I was on a mid-afternoon Tube ride on my way to a client meeting. The carriage was half empty and out of the corner of my eye I noticed a spontaneous scene: a couple, both in their early twenties, who were holding hands, smiles sculpted on their faces, their conversation free-flowing, their eyes locked on one another’s gaze, radiating an aura of carefree freedom. They were oozing energy and optimism, seemingly lost in one of those moments that seem to last an eternity, where the outside world stands still and fades in the background. Good memories!

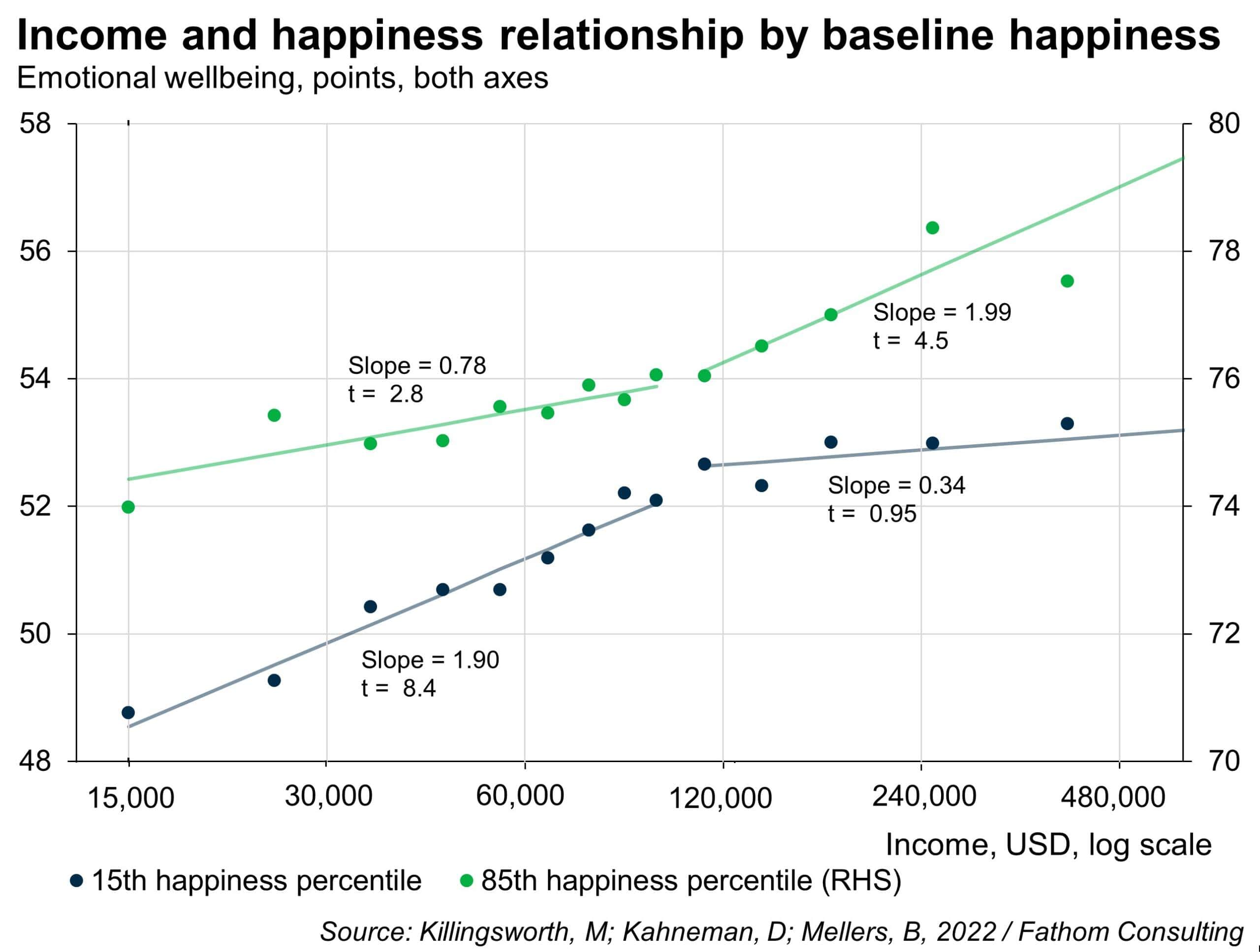

This charming scene provides a nice intro for this week’s blog post, as it triggered an association with a recent paper I discussed at work, attempting to reconcile conflicting findings on the relationship between income and happiness. In a first study, Kahneman and Deaton surveyed more than 450,000 Americans about their emotional well-being in relation to income. They found that beyond an annual salary of about $60,000 to $80,000, higher incomes did not increase overall happiness or emotional well-being; in other words, more money did not buy more happiness.

In contrast, a study by Killingsworth found that across more than 30,000 people happiness rose linearly with (log) income, even beyond $200,000 per year. In other words, he found no satiation point where additional income stopped contributing to greater reported happiness.

The current study brought the three authors together to find an explanation for the contrasting results, using the original dataset from the second study. They recognised the possibility that the flattening out of happiness at higher income levels recorded by Kahneman and Deaton could be as much a statistical artefact as a feature of the data. The authors explored whether the impact of income on happiness may not be a one-size-fits-all circumstance, but might vary according to individual happiness baselines.

By tracking people’s emotions as recorded in real time when prompted by an app, rather than through reliance on memory, the study found that for the most unhappy participants (i.e., the least happy 15% of the sample), higher incomes boosted mood significantly but only up to about $100k per year. Beyond this point, more money failed to budge their melancholy. In contrast, for individuals with average baseline happiness (i.e., individuals within the 50th percentile) the link between income and joy persisted in a straight line without satiation, as found in the study by Killingsworth. Paradoxically, the happiest subgroups (i.e., the top 15% of the sample) showed an even stronger association, with happiness accelerating with higher income levels.

One of the main contributions of the paper is to provide evidence not so much about whether higher income ‘causes’ greater happiness, but whether higher incomes may affect everyone’s happiness in the same way. A subtle difference, but an important one. By using different baseline levels of happiness, the study relaxes the standard assumption of homogeneity about consumer preferences.

When I presented this study to colleagues at the office, one of them (I’m not one to grass people up, but his name starts with ‘B’ and ends in ‘rian’) aptly pointed out that the relationship investigated in the paper was between happiness and log income rather than relative to absolute levels of income. At first, I dismissed this observation as kind of obvious, but in the spirit of questioning assumptions, I started to reflect on it.

It reminded me that, in economics, logs are often deployed as usueful mathematical tricks: for example, to allow unquantifiable concepts of utility to be expressed in terms of observable values and quantities. As such, the relationship between log income and happiness implicitly embeds a further assumption about how they may be related. This thought led to deeper, more philosophical questions: can the essence of happiness ever be truly reduced to a functional form or will assumptions always dominate the findings? If so, can we actually ever pinpoint the source of happiness?

Or perhaps it doesn’t matter. In the end, while resolving empirical contradictions is vital, it’s equally important to recognise that some aspects of life, like happiness, might be beyond the reach of assumptions and experiments. It’s in these uncharted territories of human experience where we often find the most authentic joys. As we traverse through life, moments of genuine happiness are self-evident to those who experience them or those attentive enough to notice them.

Take the couple on the Tube: I would gladly pay a significant amount of money to anyone able to guarantee that level of happiness at a flick of finger, even for a moment. And I don’t consider myself an unhappy person. Watching this intimate joy unfold as the train rumbled on, no methodology was needed to recognise happiness as a self-evident truth – it was luminous to anyone who cared to look up from their phones. It may therefore not be in the source, assumptions, experiments or income that we find happiness, but in the experience itself. Real happiness shone right in front of me – unassuming, unconstrained and beautiful in its ephemeral freedom. Or perhaps this is simply my midlife crisis kicking in… either way, the case is far from closed.

More by this author

Maple syrup-flavoured synchronicity