A sideways look at economics

I once read an anecdote about a young Pablo Picasso in which he was several months behind on his rent. The landlord came by and told him that if he didn’t come up with the money he’d be evicted on Tuesday. But Picasso exclaimed, “Before you kick me out, just think, years from now people will look at this building and say the great Picasso lived there.” The landlord looked at him blankly and said, “And if you don’t come up with the money, they can start doing it on Tuesday.” If I were to paint you a picture of the rental market in London right now, it might actually be something like a Picasso painting — all disjointed, a bit surreal, and costing an absolute fortune.

I speak as someone who knows. Having begun work here at Fathom Towers just a few weeks ago, I’m naturally excited to be moving into my first London apartment tomorrow (I have written previously about the disappointment of having to spend my placement year with Fathom working from home in Belfast during the pandemic). However, the journey to get here has been anything but stress-free — all because of rising rental costs, plus the bidding wars that people are now being forced to go through to secure the apartment they’ve set their heart on.

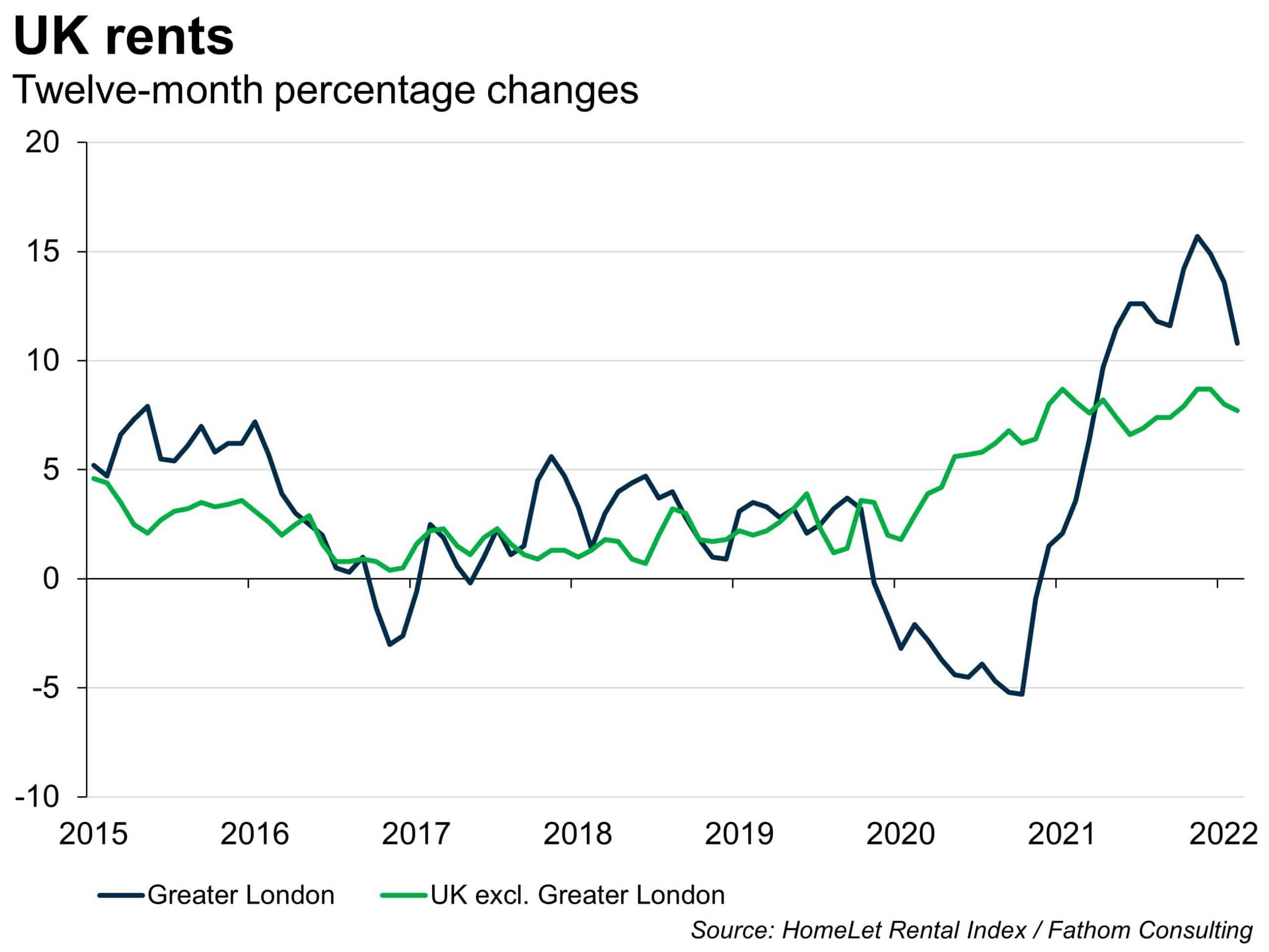

A recent survey revealed that 40% of under-30s spend more than 30% of their disposable income on rent, a level which experts deem to be unaffordable at the best of times, never mind during a cost-of-living squeeze. The under-30s are worse affected than any other working-age group. According to HomeLet, the UK’s largest tenant referencing firm, rents in Greater London were up 10.8% in August versus last year. The ongoing return of people who had previously left the city during the pandemic, as well as multiple cohorts of recent graduates all moving to the city for the first time, have caused demand to skyrocket. Meanwhile, the stock of available properties to rent nationwide has plummeted to 46% below the five-year average, according to Zoopla, as investors sold their properties to benefit from the booming sales market as a result of the stamp duty holiday introduced in July 2020. In addition, increasing taxes and stricter regulations are making it more expensive for landlords to let out their properties.

All of the above conspire to create an incidental mismatch in supply and demand, the result being an extremely competitive market, with many newly-listed apartments attracting bids far in excess of their listed rental price.

During my own property search, one landlord told me he was struggling to deal with the “sheer volume of interest” after receiving 60 enquiries within minutes of advertising his property. Many letting agents I spoke to told me that they expected their apartments to be let for up to £500 more than the listed monthly rental price. This has led to prospective tenants being asked to submit offer forms containing the maximum rental amount they are willing to pay each month, with the apartment being offered to the highest bidder in most cases. This system is similar to what’s known as a First-Price sealed-bid Auction (FPA).

In an FPA, every bidder (i) has a valuation [v(i)] which represents how much they value the object up for auction. Bidders simultaneously submit their bids [b(i)] in sealed envelopes to the auctioneer or owner of the object. Once all bids have been received, the object is awarded to the highest bidder, and the price they pay is equal to their bid.

Of course, the dilemma for the bidder is how to maximise their chances of winning the object (by bidding higher than all the other bidders), while at the same time bidding as low as possible in order to gain some positive surplus, [v(i)-b(i)]. Given this dilemma, what is the bidder’s optimal bidding strategy?

As a simple example, consider an auction in which a piece of artwork is up for grabs. Alice values the artwork at £100 (obviously, it’s no Picasso!). If Alice is rational, she would never submit a bid greater than £100 as her net payoff from winning in this scenario would be strictly negative. Essentially, what Alice would end up paying for the object would exceed the valuation she attaches to the object. Similarly, if Alice bids exactly £100 then her net payoff from winning in this scenario would be zero. If Alice bids less than £100 then her net payoff from winning in this scenario may be positive but the exact gain depends on the other submitted bids.

Let’s suppose there is only one other bidder in the auction, Bob, who bids £90 for the available artwork. The optimal bidding strategy for Alice in this scenario is to bid £90.01, i.e. the smallest increment above the second highest bid in order to win the auction. In this case, Alice has shaded her bid below her own private valuation and as a result gains a net payoff of £9.99. The difficulty for the bidder arises because in a sealed-bid auction Alice only knows her own valuation, and does not know Bob’s valuation or the bid he submits. In Game Theory this is referred to as a Bayesian game, where information about aspects of the players’ preferences is incomplete. In reality, the only way to deliver the outcome in which Alice bids £90.01 would be through an open-bid, repeated-round auction where bidders can witness the bids of others. But landlords have no incentive to do this, as the second-guessing nature of sealed-bid auctions is what leads to higher bids in the first place.

Landlords may try to shape your expectations of other bidders’ behaviour by telling you that they expect bids of up to £500 above the listed monthly rental price, but there is no way of knowing if this is true. When you submit your own bid, you do not know how many other bids have been submitted or how high those bids are.

Since it would be irrational for prospective tenants to bid higher than the value they attach to an apartment, it must be that their valuation of the property is higher than it would have been during normal times. According to Robert Cialdini, a US psychologist and author of the book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, there are two possible reasons for this.

The first is the principle of scarcity. The stakes are often high during a bidding process, as is the case with finding an apartment in London right now. Every time you lose during a bidding process, that is one less apartment available to you from the dwindling stock of apartments to rent. As humans, we tend to overvalue things we think will run out. That’s why advertising headlines like “Hurry – Sale Ends Tomorrow” never fail to perform.

The second is the principle of social proof. In other words, if everyone’s doing it, it’s casually accepted as the given norm. And this indeed was true during my own apartment search, as I eventually came to terms with the fact that I would have to blindly follow the herd and bid above the asking price.

Ultimately, it paid off and I’ve now secured my first apartment. I sincerely hope that it will serve me well for many years, because if London rents continue to spiral like they have recently, I’m sure that many of us will be dreaming of discovering an old Picasso masterpiece in the loft — we’ll probably need it to pay the deposit!

More by this author