A sideways look at economics

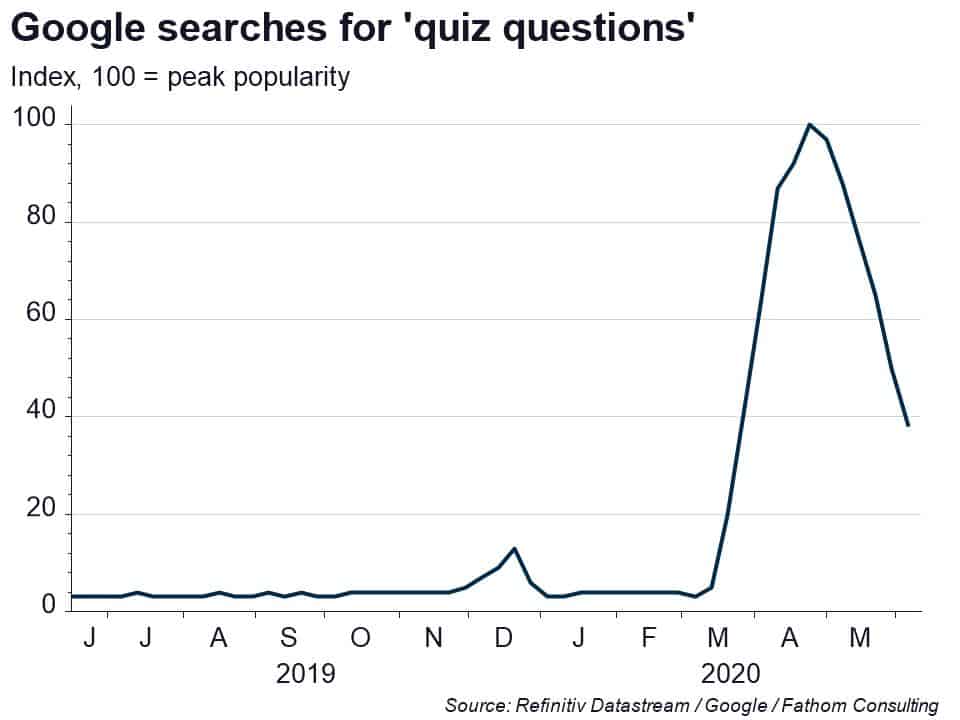

With many favourite pastimes falling victim to COVID-19, there had to be some winners emerging from the dust. Peloton, Netflix and Zoom are among those that have seen their share price rocket during lockdown, as people search for alternative leisure activities. Another serious winner has to be quizzing: virtual quizzes are gripping the nation. They bring friends and family together, and the only consequence from a wrong answer is your reputation. However, what if money were on the line? Would you take the risk of having a guess?

Those of you who binge-watched the ITV drama Quiz during lockdown will know where I’m heading with this. Once money is on the line, your fun lockdown activity can give rise to an interesting study into behavioural economics and attitudes to risk. The three-part drama followed the story of Charles Ingram, who won the jackpot on the popular TV show, Who wants to be a millionaire? What should have been a success story, turned into the scandal of the century, where he was accused of cheating after taking a ‘guess’ on the one-million-pound question.

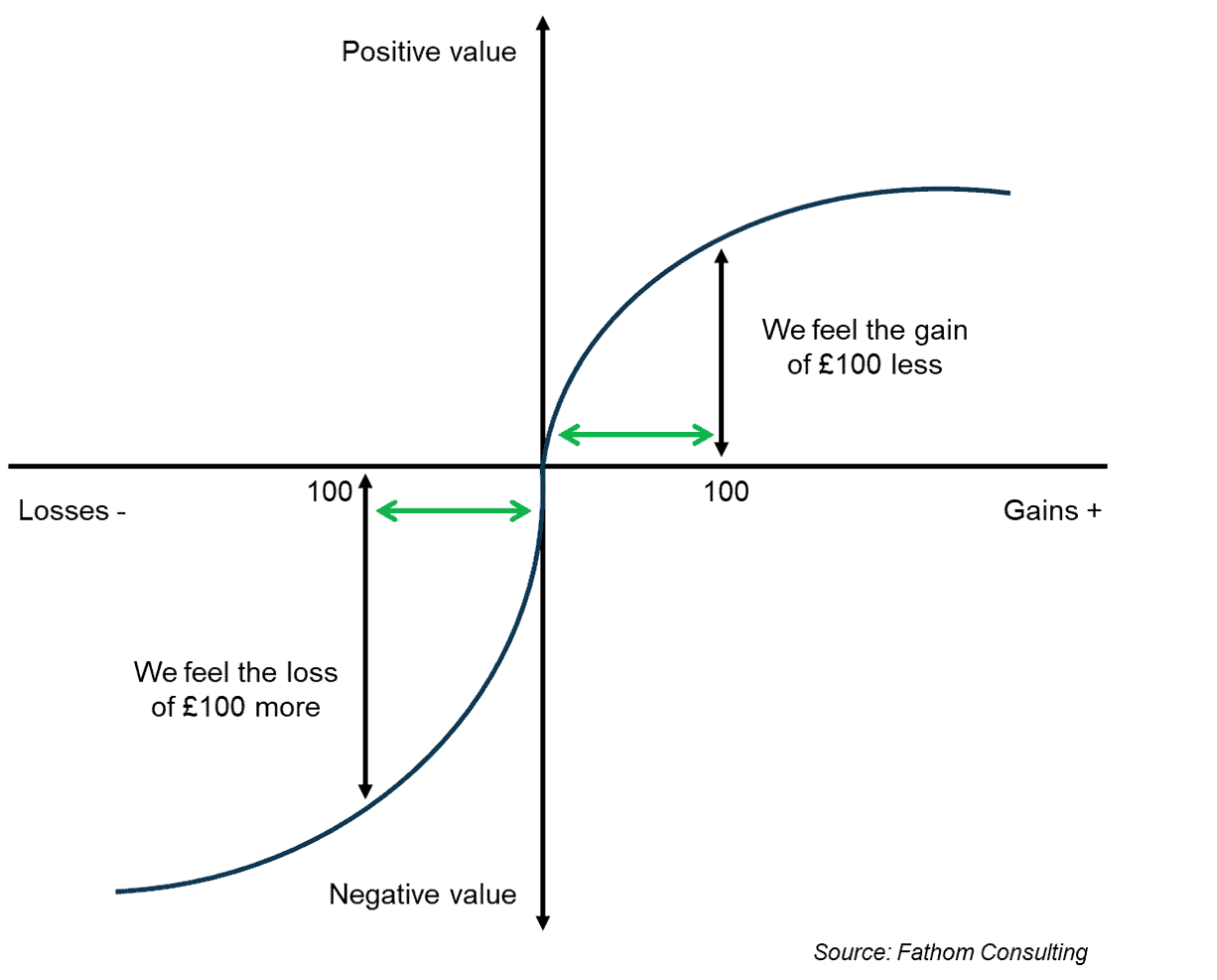

Aside from making great TV, you can look at the scandal as evidence of how behavioural economics can work and cast insights in the real world. In past blogs we have touched on prospect theory, an aspect of behavioural economics, developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, that describes the decision-making process for an individual when faced with a choice that involves risk and uncertainty. The theory postulates that an individual will make that decision based on perceived losses or gains, relative to their current position. It goes on to explain that when most individuals are faced with the prospect of gaining something, they will be risk-averse and value not making losses more highly than they value making gains (this is explained in the right-hand side of the chart below). By contrast, the behavioural economists found that when faced with losses, individuals are risk-seeking. In other words, they take risks to minimise their losses, even though that might lead to even bigger losses.

When Charles Ingram was asked the million-pound question (that he did not know the answer to), he faced a choice: walk away now with the £500,000 already won, or answer the question and, if you get it wrong, walk away with ‘just’ £32,000, putting £468,000 at risk. Prospect theory overwhelmingly suggests that he would choose the first, safe option (since, if he was ‘normal’ and his utility function looked something like that above, the utility he would gain from the additional sum would be far smaller than the utility he would lose from the loss).

Assuming, as Charles Ingram made out, that it was a complete guess, then he had a 25% chance of getting the answer correct. According to prospect theory, in this scenario, you have two choices: £500,000 with certainty, or an estimated pay-off of £274,000 from taking the risk (£32,000*0.75 + £1,000,000*0.25). The estimated pay-off from the riskier option is far less than that of the £500,000 certain option, meaning you would have to be extremely risk-seeking to go with the gamble. Faced with that choice and those odds, you would thank the audience and walk away with a nice £500,000 in the bank, right? However, Charles Ingram didn’t. He ‘guessed’ an answer that he had never heard of and walked away with one million pounds.

His behaviour doesn’t fit that of a typical person on the curve above, hence the investigation into the cheating scandal, also known as ‘cough gate’. Would you put £468,000 at risk if you didn’t know the answer?

As a full-time economist, I’ll stick to using my detective skills solely when I’m binge-watching Death in Paradise, and my success rate is low at that. So, I’m not going to comment here about whether or not he’s guilty. That’s not the main purpose of this blog, and is best saved for lively family debates.

While a simple quiz show can be used to examine behavioural economics, on a more serious note, how does it relate to what we are all going through now? We are in deeply uncertain times, battling an invisible enemy. The whole country is making decisions that lead to sacrifices to avoid greater losses. When faced with a decision where the risk is to your health, or that of your loved ones, for most, the certainty and security of staying inside is worth more than a bit of socialising or a trip to Barnard Castle. The other side of the coin is illustrated by healthcare workers who show that they value the health of others more than the perceived risk to their own health from working in a hospital environment. They take risks to minimise the losses for us. And we are all so grateful for that.