A sideways look at economics

While this blog usually offers a more light-hearted look at economics, this week a more serious tone seems appropriate. This Sunday marks the centenary of the end of hostilities in the First World War. Poignantly, this year is also one of every seven[1] where Remembrance Day falls on Remembrance Sunday, when ceremonies at London’s Cenotaph and at memorials around the world will commemorate the war dead.

Everyone will mark this period of remembrance in their own way. In the UK, many will wear a red poppy as a mark of respect for the British soldiers who lost their lives during the two world wars and in conflicts since. Some will turn their thoughts to their own family members who died, or will listen to relatives’ first-hand experiences of the war years. However, one hundred years on, there are few who can directly relate to us the personal cost of living through two world wars. A quick poll showed that, while many relatives of Fathom employees had gripping experiences during the world wars as both combatants and civilians in several different countries, only around a third of Fathom employees have met a relative who was alive or fought during the Great War, and only one still has a living relative of that period. While almost all have met survivors of the Second World War, there will come a point in the not-so-distant future where the direct memories of that war will fade as well. As economists, we might therefore reflect also on the longer-term macroeconomic costs that the world wars imposed, and the lessons we can learn from them.

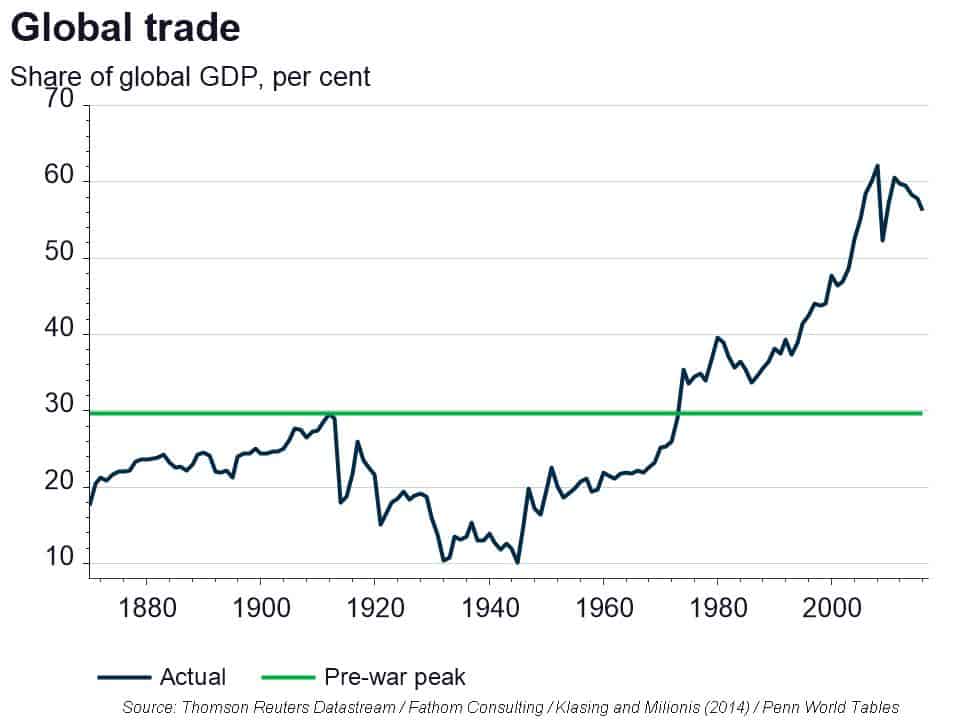

War between countries adversely affects both their diplomatic and economic relationships. The need for economic independence from adversaries, the breakdown of physical channels of commerce and general distrust among countries depress the amount of global trade. A growing literature that considers the impact of conflict on gravity models of trade shows that these effects also spill over to countries not directly involved in conflict as belligerents become more protectionist,[2] and even reduce trade between allies by up to 50%.[3] Therefore, wars have a significant negative and persistent impact on the global level of trade, especially major conflicts such as the First World War. Measured as a share of global GDP, international trade, suppressed by two world wars and the Great Depression, did not reach its pre-war peak again until 1973. In other words, it took six decades for the global economy to recover from the shock of the First World War.

Compared to a very simple counterfactual where, instead of falling during this period, global trade continued to grow at its long-run average rate,[4] global trade as a share of GDP in 2016 was nearly 30 percentage points lower than it would have been without the shock of the war years, demonstrating that the shock to trade has an effect even today. By applying estimates of the impact of a large sample of wars on bilateral trade relations, Glick and Taylor (2005) found that the global trade costs of the First and Second World Wars rivalled their direct costs in lost lives and physical and human capital.

As our personal connections with the tumult of the early twentieth century fade, we should nevertheless continue to remember the consequences of the two world wars, even beyond the lifetimes of those that witnessed them at first hand. This seems particularly important in the current global climate, where isolationism and mistrust among nations are once again on the rise.

[1] Specifically, a given date falls on the same weekday every five, six, eleven and six years, recursively — which averages out at seven.

[2] Reuven Glick and Alan M. Taylor. ‘Collateral Damage: Trade Disruption and the Economic Impact of War’, NBER Working Paper No. 11565 (2005).

[3] https://www.defense-realms.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/kamin_the_impact_conflict_trade_ices_2015_grenoble2.pdf and https://www.etsg.org/ETSG2015/Papers/323.pdf.

[4] The 1914-1972 period includes the years of the Marshall Plan and much of the post-war recovery in Europe, thus excluding these positive shocks to trade from the long-run growth.