A sideways look at economics

What should your dream job look like? Probably you will tell me that it should be very interesting, provide you with an excellent work-life balance and at the same time offer you a compensation package that positions you at the top of the income distribution. I am sorry to be the bearer of such sad news, but you can only pick two options out of the three: welcome to the impossible trinity of the labour market.

In 1999, Canadian economist Robert Mundell (1932-2021) won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his contributions to the theory underlying ‘optimal currency areas’, a study of the conditions under which a group of countries can be successful in forming a monetary union. Probably his most famous theory was the so-called ‘impossible trinity’, which states that monetary unions cannot have at the same time a fixed exchange rate, independent monetary policy and full mobility of capital.[1] Inspired by this great economist, I decided to borrow his term and apply it to a matter that has been in my head for months – what trade-offs people face when they choose where to work.

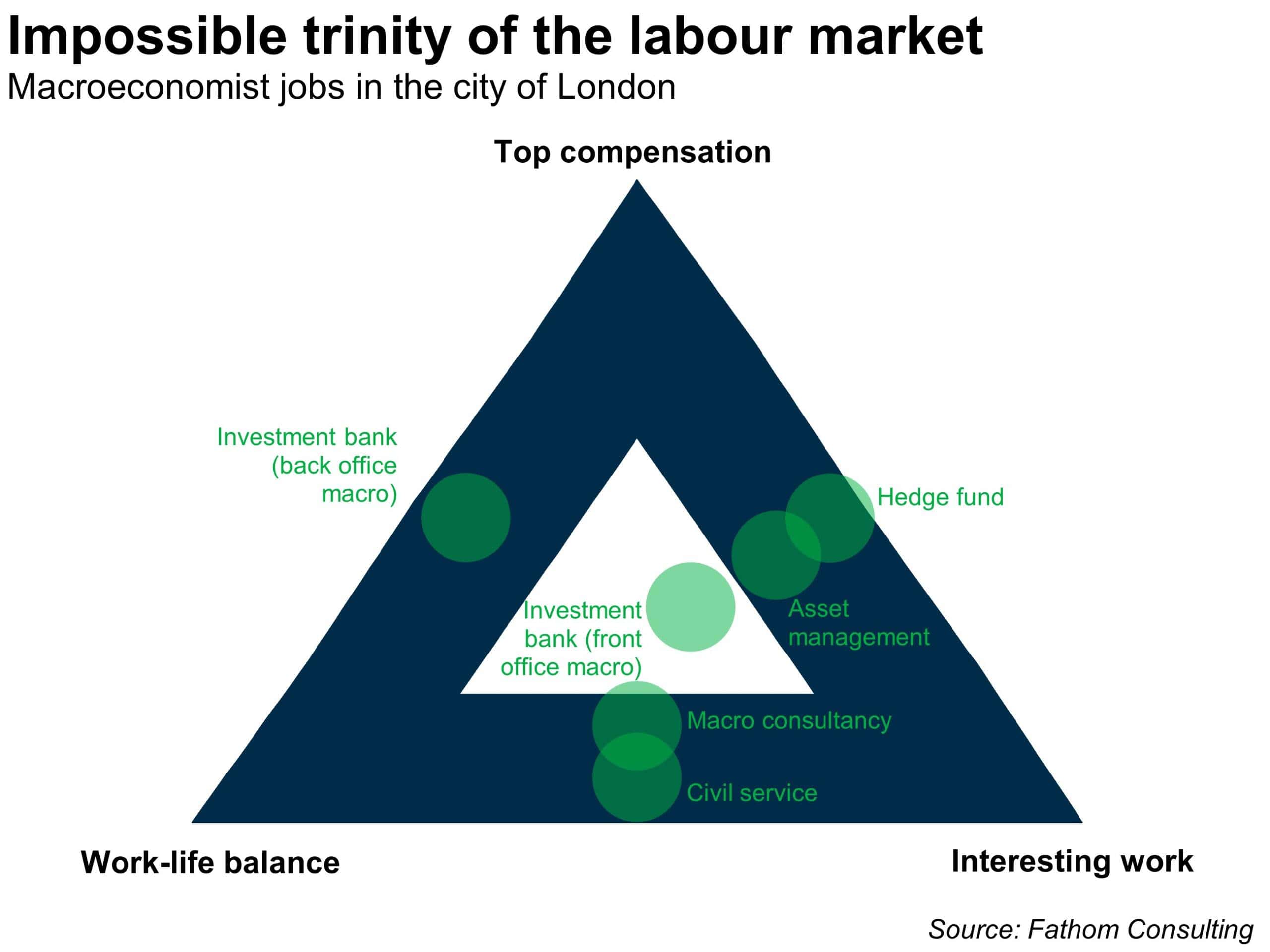

The reason I have been a bit obsessed about this topic is that I have myself faced – and still face – these trade-offs. I have never seen them manifest themselves so clearly as from the moment I moved to London just over a year ago: as one of the biggest financial hubs in the world, London offers a wide range of job opportunities across different institutions, all of them with their own realities in terms of hours worked, the nature of the job or pay scale. It soon became clear to me that you cannot have it all, and that I (and you too) essentially face what I have coined as the ‘impossible trinity of the labour market’. Let me illustrate what I mean, using examples from typical job listings for an economist in the city of London.

I know there is a lot to take in in this chart, so let’s break down each of the choices available:

Option 1: top compensation and interesting work (upper right)

The most representative example of a job on this side of the triangle is to work for a macro hedge fund. These institutions hire economists to undertake top macro research and solve interesting (and complex) problems in financial markets. A macro hedge fund allows you to put the results of your analysis into practice by placing trades that are consistent with your views about the world economy, which is quite cool. On top of that, they offer a very juicy compensation package. But if hedge funds are so amazing, why isn’t everyone working for them? The reason is that they are widely known for their long working hours amidst a highly stressful and competitive environment. Hedge funds usually offer very little flexibility when it comes to working from home or vacation dates, and it can be worse than that. Since you are betting on some currency or bond to go up or down, there is a risk that the market will move in the opposite direction (sometimes despite having the macro analysis correct!), which can result in big losses for the fund. Consequently you could get fired, although the risk also applies the other way around: if you get it right you can see your compensation rise exponentially. It is therefore a very risky job and not for everyone, but many smart and ambitious people can thrive in this environment.

Option 2: work-life balance and interesting work (bottom)

This category includes mainly macro consultancies and civil service jobs. They offer very interesting and technically demanding jobs at the heart of policymaking, as well as very good benefits when it comes to working hours, working from home arrangements, parental leave, etc. But again, if they are so great, why is everyone not working there? The reason is that you will be sacrificing money, and this is something that can be very important for many people, especially considering how expensive it is to live in London. I would highlight the remarkable case of the Bank of England – you might be very surprised at how low the pay is there, considering the prestige and importance of the institution.[2] As you can see in the chart, macro consultancies such as Fathom are a bit further away from the extreme, which means that they offer a better salary, at the cost of a slightly less favourable work-life balance and benefits. It’s all about trade-offs!

Option 3: top compensation and work-life balance (upper left)

This is a subjective call, but I have included here back-office economist jobs, which are usually found in investment banks. My point is not so much that these jobs are not interesting at all, but that they are a lot less interesting relative to the other alternatives you can see in the triangle. The reason is that investment banks have been heavily regulated over the past few years, which has resulted in a rampant amount of bureaucracy that one needs to deal with in these kinds of jobs. Furthermore, the incentives for being productive and innovative are reduced, since workers are not being assessed on how much profit they have generated for the company – which results in more static and uninspiring working processes. On the bright side, back-office jobs at investment banks can afford very generous compensation packages relative to the hours you work, and usually have a friendly working atmosphere (people are not competing against each other), on top of excellent work-life balance.

The main takeaway here is that there is no ‘winner’ option, because where you position yourself in the triangle highly depends on your personal circumstances and your expectations regarding your job. During this first year in London, I have had the opportunity to meet people from all sides of the triangle, and I have found it really interesting to hear their stories about why they have chosen their employers. When getting into the details, I realised that these people know exactly what trade-offs they face: in other words, they have implicitly been thinking about this triangle! It’s just that, until now, nobody had formalised this decision-making process.

Another fascinating feature of the ‘impossible trinity’ triangle is that not only does it vary across people, but also within people. In other words, the triangle is dynamic. As the professional and (most importantly) personal circumstances of people evolve over their lifetimes, so do their priorities. A classic example of this in the world of economists is to move from option 2 to option 1 or 3. This is to say, somebody who for example starts working for a macroeconomic consultancy for some years, prioritising the massive learning opportunities that consultancy can give you (but sacrificing a high pay that could be obtained elsewhere), may then decide to ‘capitalise’ on this effort by moving to an investment bank where they will be able to expect a rank and a level of compensation that otherwise would had taken a lot more time to achieve. There are other combinations, but they are less common. For example, I would argue that switching from either of the two options with top compensation (1 and 3) to option 2 is less common from an economic point of view, since your reservation wage[3] is much higher. Finally, moving from a back-office job (option 3) to a front-office job in a hedge fund or asset management firm (option 1) or a macro consultancy or civil service role (option 2) is certainly possible, but also does not happen very often: most likely this is due to a combination of lower tolerance for demanding working hours (it is very hard to come back to this reality once you are accustomed to leaving the office at 5 pm), and a higher reservation wage, in the case of moving to an option 2 job.

If you want to hear a real-life example, when I decided to move to London I was very clear that my new job would have to be really interesting and challenging, which already ruled out option 3. To be honest, given that non-negotiable requirement being satisfied, I was (and continue to be) quite indifferent between earning a top compensation at the cost of very harsh working hours, or having a better work-life balance at the cost of a lower salary. This is because I firmly believe that when you are in your 20’s you should work very hard, and try to upskill and increase your knowledge as much as possible. I once heard a quote that has stayed in my mind: “The best way to secure a mediocre career is to have a 9-to-5 job in your 20’s.” Perhaps that is too strong a way of putting it, but you get the idea. So, what ended up happening is that Fathom’s offer was the most attractive one, and so far, I feel very satisfied in my choice of option 2. However, it is certainly possible that in the future I will want to move around the triangle, depending on what I feel I may need at any given stage in my life.

Before I finish, I would like to clarify two important points. The first is that the mapping of the industries in the triangle has been done in a completely subjective way, taking into account both my personal views and the opinions of the many economists I have met during my career, which in most cases have matched with mine (and for that reason, I strongly believe that on average I am very close to the truth). The second point is actually not mine. When I enthusiastically presented my idea of the ‘impossible trinity’ triangle to my cousin Vicente over Christmas dinner, he pointed out that many people do not have the option to choose where they want to be in the triangle, because either they are ‘blue collar’ workers, or work in industries or cities where the options to move around are much more limited. In other words, even being in this triangle can be considered a privilege.

Nevertheless, I strongly believe that my triangle theory provides a very useful framework to think about the trade-offs you make when you choose where to work. And perhaps — at the risk of appearing both too ambitious and rather comical — it’s not impossible to dream that, one day, the impossible trinity of the labour market will make it into some ‘psychology of decision-making’ textbook!

[1] https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/glossary/policy-trilemma-the-impossible-trinity/

[2] https://www.fnlondon.com/articles/half-of-bank-of-england-staff-think-they-are-underpaid-20230324

[3] The reservation wage is the lowest wage a worker is willing to accept for a particular type of job.

More by this author

What is a professional economist?