A sideways look at economics

What do economists know about relationships? After all, you “Can’t buy me love” as the Beatles said. But perhaps listening to an economist’s views isn’t so crazy. Ultimately, many economic models of relationships are founded on the same key theme as any Mills & Boon novel — that is, the idea that ‘coupling up’ provides some kind of additional benefit to both parties.[1] To the average paperback writer, this benefit might simply be the additional joy that a relationship can provide. Economists wouldn’t disagree but might add other advantages such as the division of labour in household tasks and additional income for the poorer partner.[2] And they say romance is dead…

So, if marriage is beneficial to all individuals, why isn’t everyone married? The economist’s explanation is that courting takes place in an imperfect, decentralised market, one in which not all agents are guaranteed to meet their perfect partner. Obviously, the probability of making a match depends on a person’s attitude (i.e. if they’re proactively looking for a partner or whether they simply say “Let it be”). Why doesn’t everybody search proactively? Well, it requires effort and effort is costly.[3] Ultimately, an individual’s efforts to find a match will be such that the marginal cost of searching is equal to the expected benefit of a match.[4]

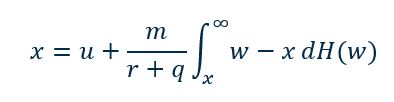

There are also different qualities of matches between couples. After all, just because someone says “she loves you”, it doesn’t mean that you love them back! The better two people match (i.e. the more in love they are), the more utility they will derive from the match. Consequently, when presented with the chance to partner with another person, each individual must weigh up whether they could be happier with a different partner. Ultimately, people couple up if the expected utility of a match exceeds a certain threshold (x):

where m, r and q represent the matching, discount and separation rates, u represents the instantaneous value of being unmatched and w the value of being in a match.

A few stylised facts emerge from this so-called ‘search model’:

- First, the more likely a person is to meet future partners, the less likely they are to accept a partner now. This is easy to understand since it implies that the rejection of one partner is followed by a shorter wait for the next opportunity. This implies that, while dating websites increase the likelihood of meeting a partner, they also make people pickier when choosing partners

- Second, a person is more likely to accept a partner now, if they think the chances of a future breakup are higher. Intuitively, if relationships are less likely to last, the risk associated with entering a bad match is small as there’s always likely to be an opportunity to get back ‘on the market’ and re-couple in the near future (there are fewer commitment issues involved)

- Third, a person is also more likely to partner up if they discount the future more. This makes sense since a less patient individual will be more willing to settle for an okay match now rather than wait for ‘the One’ at some point in the distant future — “not looking for Mr Right, just Mr Right Now” as I’ve heard it described

- Fourth, the greater the utility that a person derives from remaining single, the lower the likelihood of them agreeing to a match. Again, this is perhaps an unsurprising finding. The social stigma faced by a single person is undoubtedly less than in the past. This would suggest (all else being equal) that fewer people ought to be coupling up

While an insight into economists’ views of relationships might be interesting to some, it’s also something that serves a more practical purpose for those interested in macroeconomics. There’s actually a significant degree of overlap between the way in which economists view dating and labour markets. Indeed, many of the theories and techniques used to analyse relationships are at the heart (yes, that pun was intended) of labour economics.

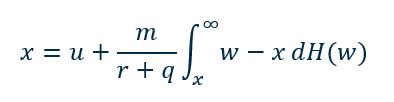

‘Search models’ are therefore also used to model frictional unemployment. After all, job searches also take place in a somewhat decentralised market and the quality of matches also varies. Hence, it’s easy to adapt the above model so that it becomes an interaction between workers seeking jobs and firms hiring them. The outcome is remarkably similar, with the threshold for accepting a match being known as the reservation wage (x):

As before m, r and q represent the matching, discount and separation rates, u reflects the instantaneous value of being unmatched (which is now interpreted as unemployed) and w the value of being in a match (i.e. the wage).

Many labour economists prefer these models to the classical supply and demand framework since they provide an easier lens through which to understand unemployment. Indeed, the greatest shortcoming of the classical framework is that it always shows full employment unless additional assumptions are introduced.[5] The same criticisms can’t be levelled at ‘search models’ and ‘matching models’[6] in which unemployment plays a central role.

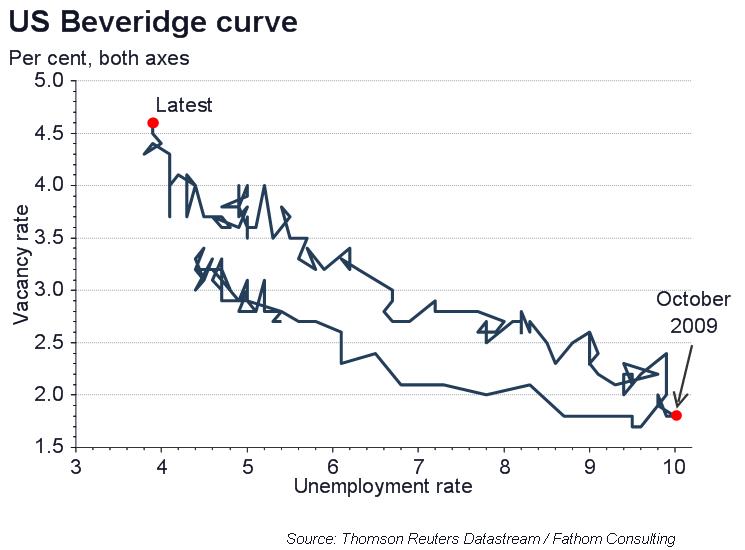

For macroeconomists, the end goal of such models is the Beveridge curve — the inverse relationship between the vacancy and unemployment rates. When an economy is booming, the vacancy rate will be high (i.e. firms will be hiring) and the unemployment rate will be low. When a recession hits, unemployment will rise as workers are laid off, and vacancy rates drop as firms stop hiring. And, the position of the curve tells a story in itself — if it moves towards the upper-right corner of the chart, there will be a higher unemployment rate for a given level of job openings. In other words, the matching process becomes less efficient.

And to garner a greater understanding of the Beveridge curve, we can once again turn to our analysis of dating. Indeed, many of the factors affecting both the position of the Beveridge curve and an economy’s position on it, are also present in the world of dating. For example, where apps such as Tinder increase the likelihood of meeting potential partners (but reduce the likelihood of accepting those matches), LinkedIn now enables workers both to find and compare potential jobs. And while changes in social norms may affect the likelihood of couples splitting up over time, business cycles affect the likelihood of workers being laid off. The utility of remaining unmatched might reflect unemployment benefits or individuals’ valuations of leisure time. So, to help get a good understanding of labour markets, perhaps all you need is love.

[1] Admittedly, the advent of dating websites probably means that the degree of effort required nowadays may be less than in the past.

[2] Dale T. Mortensen, ‘Property rights and efficiency in mating, racing, and related games’, The American Economic Review, 72/5 (1982), pp.968-979.

[3] Economists would of course refer to this as a surplus which increases the utility of the couple, but that doesn’t quite sound so appealing.

[4] If income is shared between partners, then coupling up might also act as neat way of pooling risk in times of recession.

[5] According to the classical framework, if wages and employment are set according to the intersection of demand and supply then the market clears. That’s to say that every person who’s willing to provide labour at the going wage rate has a job. Since unemployment is, by definition, involuntary it will be therefore always be equal to zero.

[6] Matching models are similar to the ‘search models’ but also incorporate a greater description of firms’ motivations for hiring workers. For more, see: Barbara Petrongolo. and Cristopher A. Pissarides, ’Looking into the black box: A survey of the matching function’, Journal of Economic Literature, 39/2 (2001), pp.390-431.