A sideways look at economics

I recently travelled to Seoul to visit a friend who is doing her master’s there. The trip was a good mix of learning about South Korean history and culture through visiting temples and museums, and consuming barbecue (and a fair amount of soju, a rice spirit rather like vodka). One of the most interesting parts of my stay was comparing what it’s like being in your 20s there and in the UK. I was explaining the crazy rental market in London, but when my friend told me what was going on in the rental market in Korea – particularly the size of people’s deposits – my jaw dropped.

Apparently there are two main ways to rent a property in Korea:

- Jeonse: in the jeonse system, you pay a deposit that is usually a staggering 50-70% of the property’s value. The landlord invests the deposit and earns returns on it. The tenant is responsible for utility bills. After the tenancy ends, the tenant gets the deposit back. If the property loses value during the lease, the tenant can get this money back through a decreased deposit when renewing the lease. If it increases, the lease will go up upon renewal.

- Weolse: in the weolse system the tenant pays a smaller deposit than in the jeonse system, but still usually a hefty 10 to 20 times the monthly rent, and makes monthly payments on top

The jeonse system makes it incredibly difficult to enter the rental market in South Korea. According to the Korea Real Estate Board, the median jeonse price was 178.36 million won at the beginning of 2023, or around £117,000.[1] To pay such a large deposit, many tenants have to take out a bank loan. Furthermore, the system does not give a lot of flexibility to tenants – if the tenant drops out before the end of the contract period (usually 24 months), they risk losing large sums of money. These are among the reasons why at least 42.5%[2] of Korean Gen Z and Millennials still live with their parents, according to Statistics Korea.

Moreover, the jeonse and weolse systems give very little protection in the case of fraudulent landlords. If the landlord has a large amount of unpaid taxes or liens on the property, the government may put the apartment up for auction. Profits from the auction are then used to pay the liabilities of the previous landlord. Since other liabilities, such as taxes, have a higher priority than paying back the deposit, the tenant risks losing part or all of their deposit (it is possible to get an insurance on your deposit, but with the deposit already so expensive, only 20%[3] of jeonse tenants choose to fully insure their deposits). Jeonse fraud, where landlords use their tenants’ deposits to buy multiple homes and then refuse to pay the deposits back, is not uncommon. In 2023, the police uncovered over 4000 cases of jeonse scams, with the total financial damage for victims reaching 510.5 billion won (£300 million).[4] Such wide-scale frauds are made possible partly due to information asymmetry between the tenant and landlord, whereby the landlord is not obliged to give information on national taxes and real estate market prices to tenants.

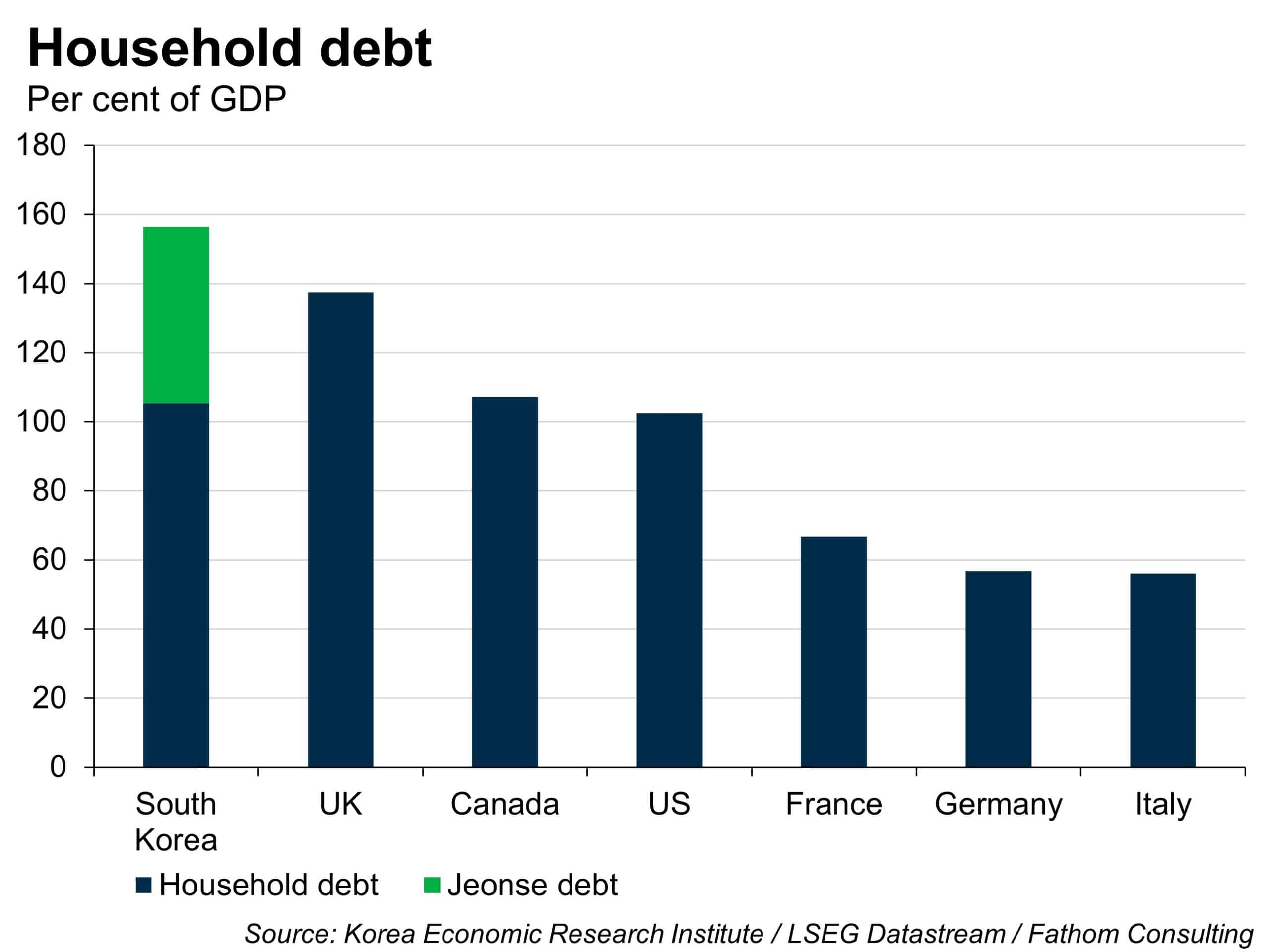

With all this in mind, it is perhaps not surprising that Korean household debt as a share of GDP is high. However, official statistics do not count jeonse debt as part of household debt, which skews the Korean numbers. Excluding jeonse debt, Korean household debt as a share of GDP is 105%, lower than the UK, at 137%. According to research from the Korea Economic Research Institute, the figure stands at 156% when including jeonse debt, as can be seen from the chart below.

While all of this may sound daunting, there are some positives: once tenants have managed to afford the initial costs of entering the property market, they can use the money they get back from their deposits to put down a fresh deposit. Moreover, they are basically living rent-free, as their deposits are returned at the end of the contract (although for most people their ‘rent’ is the interest on the bank loan they took out to afford the deposit). Landlords profit by treating the deposit as an interest-free loan which they can invest and earn returns on. It is also common for parents in Korea to save up for their children’s first jeonse deposit, similar to how UK parents save up for their children to go to university. So, if your family can afford the initial costs, there are some benefits to this system.

You may wonder why, with the entry barrier to renting so high, renters don’t just buy homes instead. After all, the median house price in Korea was 273.86 million won at the start of 2023, or around £179,000. The median jeonse price, by comparison, was 178.36 million won, or around £117,000. But the jeonse system has never been superceded because it remains difficult to obtain a mortgage in Korea, so that jeonse is often the only option for people wanting to move.

Jeonse has survived periods of rising house prices, as landlords were able to pay their old tenants back with the deposits they got from new tenants (which were larger than the previous tenants’ deposits due to the increased value of the properties). Recently however the prices of houses and apartments, and along with them the size of jeonse deposits, have started falling sharply, and this is creating something of a crisis for landlords and in turn for tenants. At the trough last summer, house prices had declined by 7% from the year before, apartments by 11%, and jeonse prices by 9%. Now that house prices are falling, landlords are struggling to pay back deposits, as the new deposits they are levying are worth less than what they owe previous tenants. This is especially true for landlords who used tenants’ deposits to purchase multiple properties, expecting house prices to continue rising. The number of court cases filed by tenants against landlords for unreturned deposits increased by 60% in the first half of 2023 compared to 2022, according to the Supreme Court of Korea. Statistics from Korea’s central bank suggest that more than half of the two million people paying jeonse risk losing parts of or all of their deposit, leaving many with a large financial burden and probably driving up further the proportion of young people still living with their parents.

The way these housing problems are unfolding in Korea can be compared to how, during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), sub-prime mortgages were renewed based on the value of properties increasing. However, when the housing bubble burst and prices started declining, the holders of mortgages were not able to pay back their debt. Many lost their jobs in the ensuing recession. Learning from the past, a housing crisis can have large consequences for the financial system, threatening liquidity. Last year, fear spread of defaults on real estate projects in South Korea, causing a liquidity squeeze in financial markets.

Is this the end of the jeonse system? Will the financial aspects of the housing market be restructured, as they were in the west after the GFC? It is hard to say, as getting a mortgage is still difficult in South Korea – particularly with interest rates increasing to tackle inflation. Furthermore, after rising demand for mortgages pushed up household borrowing in Korea in August 2023, South Korea’s financial authorities put in place measures to reduce household debt and curb misuse of long-term mortgage loans.[5] So, buying rather than renting is not a viable option for many Koreans, despite the large up-front deposit costs.

There is some evidence of a shift from jeonse towards monthly rentals: In April 2022, the amount of monthly rental contracts was larger than the amount of jeonse contracts for the first time since 2011, at 50.4 per cent, as rising interest rates made jeonse bank loans more expensive. From January to April 2022, monthly rentals accounted for 48.7 percent of lease contracts. The five-year average stood at 41.6 percent.[6] Whether this shift continues will depend on multiple factors: interest rates, the difficulties of obtaining a mortgage, whether landlords are willing to shift to monthly rentals, whether the government can successfully tackle fraudulent landlords, and whether bursting the housing bubble leads to a wider financial crisis, prompting financial authorities to impose new financial regulations. These could, for example, involve a requirement for the landlord to respond to information requests from the tenant, decreasing the information asymmetry between landlord and tenant and making it easier for tenants to discover possible scams before they lock themselves into a contract. Another possible reform would be to make the return of the deposit a legal priority in the event that the landlord cannot repay their debt and the property is auctioned away. Increasing transparency and accountability would be a step in the right direction of tackling jeonse fraud.

Hanok village in Seoul

[1] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/south-koreas-jeonse-rent-free-renters-hit-by-property-downturn-2023-02-21/

[2] https://www.korea.kr/docViewer/skin/doc.html?fn=196762599&rs=/docViewer/result/2022.03/31/196762599

[3] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-12/renters-losing-life-savings-furthers-south-korea-s-inequality

[4] https://m-en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20231016001700315

[5] https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/skorea-tightens-loan-criteria-household-debt-jumps-most-2-years-2023-09-13/

[6] https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220531000599

More by this author