A sideways look at economics

In his 1999 paper: ‘Japanese Monetary Policy: A Case of Self-Induced Paralysis?’, Ben Bernanke stated:

“I tend to agree with the conventional wisdom that attributes much of Japan’s current dilemma to exceptionally poor monetary policy-making over the past fifteen years”.

In 2006, Bernanke was appointed as Fed Chair, where he remained through the Great Financial Crisis and the transition into the low-rate, Japan-style new normal thereafter, until 2014.

The kind of finger-wagging that bien-pensants like Bernanke were directing at Japan in the late 1990s is now, rightly, being directed back at them. What goes around, comes around. Japan at least had an excuse, which was that they had entered uncharted territory after the bursting of their bubble economy in the late 1980s. The US, the UK and the euro area have no such excuse. The outcome of exceptionally poor monetary policymaking (if that is what it was) had already been demonstrated, by Japan. I felt at the time Bernanke wrote those words the kind of dread that was induced when Kevin Keegan said in live commentary, at a point when England’s football team were drawing 1-1 with Romania in the knock-out phase of the 1998 World Cup:

“Only one team can win this now: England”

Hearing that line spoken, you just knew it would come back to bite him and all England supporters (the final result: 2-1 to Romania). I felt the same kind of dread when I saw Bernanke’s paper a year later.

We still don’t know how the story will end. But the latest few chapters have made grim reading for monetary policymakers across the developed world. It’s 2-1 to the forces of paralysis ten years after the recession, with rates failing decisively to escape the zero lower bound and even, in many cases testing the murky waters of negativity, growth reverting to a much-reduced trend, driven there both by demographics and by productivity growth, debt ratios rising inexorably, and inflation seemingly stuck a bit below target in most economies. Does this ‘paralysis’ arise from monetary policy being insufficiently aggressive in the face of the recession? Or can the factors that drive advanced economies to this kind of equilibrium not really be countered by monetary policy at all? Either way, the finger-wagging aimed at Japan back in the day looks ill-advised now.

However, having just returned from a business trip to Tokyo and Seoul, I can report (as many will already know) that much of the gloom about the Japanification of other advanced economies is misplaced. Japan is not so bad. In fact it’s not bad at all. Rather good, I would say. Not so much bumping along the bottom as bumping along the top, as Sir John Gieve eloquently put it in a Fathom conference a couple of years ago.

Bumping along the top in Tokyo: the rooftop bar in the Peninsula hotel

The standard of living in Tokyo is very high by global or historic standards. In a sense, this is the problem, in Japan and elsewhere. The appetite for the radical measures that might put Japan (and the rest of us) on a stronger growth path in the long term is much reduced as a consequence of the fact that life is pretty good right now, especially for those towards the upper end of the income distribution. It’s worth remembering that there has never been a better time to be alive as a human being than now, and that’s no less true in Japan than in any other developed economy. Actually, it’s also true in developing economies.

As Japanese policymakers have long known, and as we are finding out, the opportunities to take radical action are few, and tend to arise out of crisis. Without a crisis, it’s hard or impossible to manufacture the political will for anything other than minor adjustments: Japan has implemented a whole string of minor adjustments to fiscal and monetary policy over the last three decades, with no lasting impact on its long-run growth trajectory. The Great Financial Crisis offered an opportunity to take radical steps right across the developed world: in Fathom’s view, that opportunity was not taken.

We were hopeful that the election of Donald Trump would create another opportunity and that this time it might be taken. It was not: the fiscal measures enacted by the Trump administration were half-hearted and poorly directed. The new government in the UK has another opportunity, which again it is likely to spurn.

We will probably have to wait for another crisis like 2008/09 for another globally synchronised opportunity, and the evidence suggests that — even then — we will pass it up. In all likelihood, we will all tread the same path that Japan has laid down: bumping along the top.

That doesn’t sound too bad, and a casual, business traveller’s acquaintance with life in Tokyo suggests it isn’t. In fact, stagnant growth could be taken as a sign of success, as Dietrich Vollrath argues in his book Fully Grown. However…

The problems with no growth or low growth are not just the lower implied standard of living that it delivers on average in the distant future, but also the increased difficulty associated with redistribution it presents along the way. It’s relatively easy to increase the share of the pie that goes to the poor if the pie itself is growing. In that world, the rich can get better off, or at least no worse off than before, while the poor see their lot improve sharply. Loosely, Pareto-optimal redistribution. But if the pie is static or shrinking, redistribution can’t be achieved without making the rich worse off in an absolute sense — something they are likely to resist.

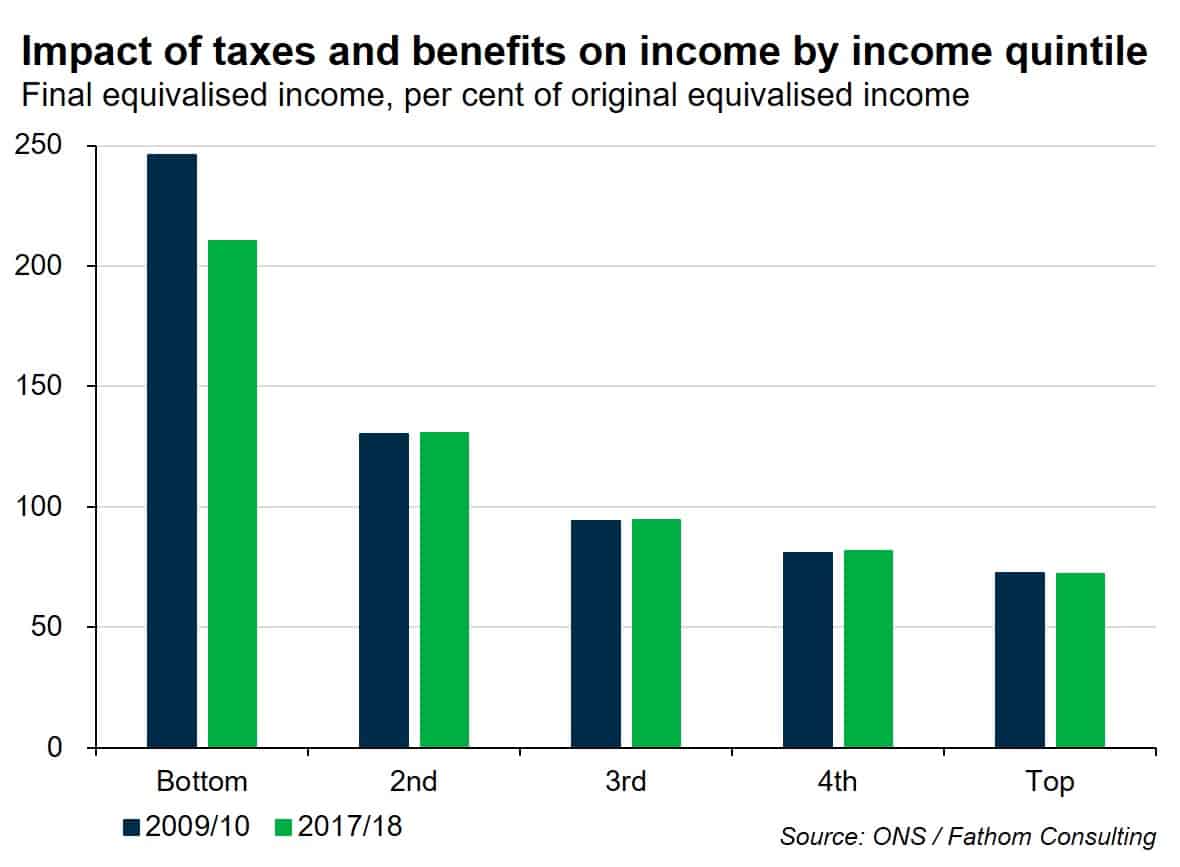

The strains are already showing. For example, in the UK between 2009/10 and 2017/18, the degree of redistribution via taxes and benefits from rich to poor (among the non-retired population) has reduced.[1] The increase in income for the bottom income quintile that arises as a result of taxes and benefits has fallen over that period, even though the corresponding ratio for those at the top end of the income distribution has not increased. It’s hard to do as much redistribution when average incomes are barely growing in real terms, as has been the case since the recession. The only way of doing it would be to make the top earners worse off after taxes and benefits than they were in earlier years.

The flat average real incomes that go with Japanification are likely to mean an ever-decreasing degree of redistribution — which might be satisfactory for the higher income earners but not for the lower income groups. If Japanification is to be avoided (unlikely), it is pressure from the less well-off that will do it.

[1] There are many ways of measuring this concept. Here I have used the ratio of final to original equivalised income for each quintile group of the non-retired population.