A sideways look at economics

When Gandalf picks the Ring out of the fire and shows it to Frodo, words glow into life that were etched into the gold.[1] Frodo says: “I cannot read the fiery letters”. Gandalf explains that they are written in an ancient script, which he renders in the common speech as:

“One ring to rule them all, one ring to find them,

One ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.”

This wasn’t just a pretty trinket, capable of helping with a party trick, but the ring of power. Apart from revealing my inner LOTR geekiness, what does this have to do with economics? Sometimes, in economics as in fantasy novels, appearances can be deceptive.

I’m aware that this weekend marks the tenth anniversary of the Lehman Brothers debacle, but I’m not going to write about that. This month also marks the fifth anniversary of something that will ultimately prove to be even more significant: the initiation of China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) project.

OBOR (aka the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI) is a plan to invest truly colossal sums in developing and less-developed nations around the world, particularly those that occupy important or potentially important trade routes for China (such as the old ‘Silk Road’). Very often, the recipient countries have been starved of substantial investment for decades, and not without reason. They tend not to qualify for funds from organisations like the IMF or the World Bank because of the parlous state of their public finances and their inability or unwillingness to comply with the off-the-shelf stabilisation policies that those organisations promote. And they often don’t qualify for development aid from western donors, because of their unwillingness to embrace democracy or to make serious progress on human rights.

The authorities in China don’t care about either of those things. They plan to extend massive loans to those countries irrespective of their fiscal position, their standard of governance or their record on human rights.

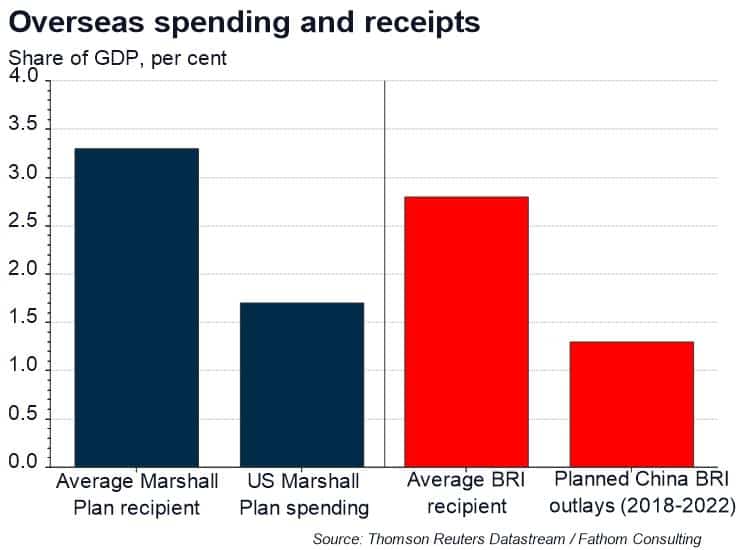

On the face of it, this looks like highly enlightened policy, akin to the Marshall Plan in post-war western Europe. The numbers are strikingly similar:

And the similarities don’t end there. The recipient countries are in a bad equilibrium, many having been recently affected by war, just as they were in post-war western Europe; and a major jolt of this sort might be just the medicine they need to get them, and their citizens, onto a much better path in future, as happened back then. And China itself doesn’t embrace democracy and doesn’t have a stellar record on human rights, to say the least. But massive investment there has transformed the economy at an incredible rate over the last couple of decades, dramatically improving the standard of living of the country’s citizens. If it works in China, why not elsewhere? Perhaps it goes: investment first, improving standard of living second, improved governance third. And even if the third thing doesn’t happen, well, two out of three ain’t bad…

This isn’t the right place for a detailed assessment of the economics of OBOR. Suffice it to say, there are good reasons to support OBOR and equally good reasons to be concerned about its effects. Here, I’m focusing on the language around OBOR; the way that has changed; and what that might imply.

The language changed in 2016. Until then, the project had been known as One Belt, One Road. But since then it has been rendered in English as the Belt and Road Initiative. The stated reasons for the change: first, concerns that the emphasis on ‘one’ in the original title was misleading and led to unnecessary competition between potential recipients — fearing that if they missed out on the ‘one’ then they wouldn’t be able to participate at all. And second, concerns that OBOR had been taken to imply a different kind of oneness — a sense of creeping control over the institutions in recipient countries.

To my ear, “One Belt, One Road” has an unmistakable tang of power about it which “The Belt and Road Initiative” lacks.

Think about the metre of the phrase: four thumping, leaden monosyllables. This isn’t a light step: de-dum de-dum de-dum… It’s much heavier than that: boom, boom, boom, boom. Like a steam press stamping out steel parts. Like Tyrannosaurus Rex approaching in Jurassic Park, making the ground shake and the water ripple. There are happier, lighter uses of this metre too, such as the Bob Marley lyrics “One love! One heart!”, but OBOR doesn’t resonate in that way for me.

And the repetition of “One” has a rhetorical intensity to it, as it does in the Marley lyrics. Think also of Churchill’s repetition of “We shall fight…”, and numerous examples of the same device in poetry. The repetition invites you to focus on the meaning of that word or phrase, even if its meaning is dark or uncomfortable. It wasn’t a mistake the first time it was stated. The author doesn’t want you to gloss over it or hide from its implications. Dwell on them. They are the whole point.

OBOR conveys no intimation of hesitancy or tentativeness. I feel, hearing it, that there’s no doubt that this will happen. I can see the acronym in my mind’s eye in raised steel lettering on the front of a locomotive or an oil tanker — or a tank — with the degree of hesitancy that implies (zero).

OBOR conveys no sense to my ear that there’s any discussion to be had about what the belt and the road will look like. That has already been decided. There’s no question in the tone. There will be no questions. It will be thus.

OBOR conveys strongly the sense that all participants will be doing the same thing. We shall be one. No: I insist. We shall be one: this one.

OBOR sounds like the vector of China’s projection of power abroad. That’s how I hear it.

BRI, by contrast, sounds hesitant and uncertain. The word “initiative” suggests that this is the beginning of something. It might work; or it might not. How it ends isn’t yet known. And the removal of the repeated “One” draws the sting from the phrase, so to speak. This is the kind of thing middle managers would say in large corporations. I can imagine a conversation like:

“What are you working on today?”

“Oh, the belt and road initiative, you know.”

“Oh, that sounds a bit dull. See you for a beer later?”

And the metre of the phrase is totally different: light footsteps, not the approach of a massive predator.

In my mind’s eye I can see the acronym appearing on the title page of a rather tedious PowerPoint presentation (“Rolling out the BRI across consumer verticals” or some such gibberish) delivered in the graveyard post-lunch slot at a conference in a mid-level hotel near the airport. Unthreatening, corporate language.

The linguistic shift was aimed at preventing misunderstanding, apparently, whether by the domestic or the foreign audience (probably both). What if, though, it was really aimed at preventing understanding? What if this isn’t just a pretty trinket, but the real thing?

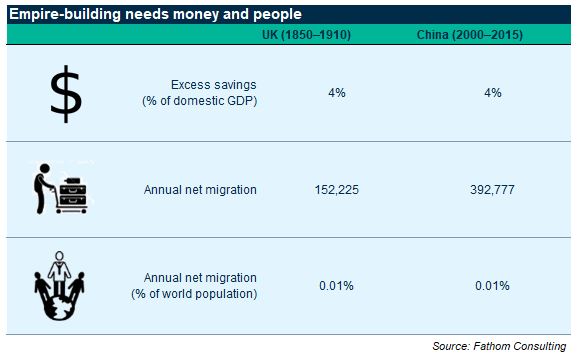

What if OBOR/BRI is really a long-term power play by China — more akin to the growth of the British Empire than to the Marshall Plan?[2] Again, the numerical similarities are striking:

Which is the closer approximation to the spirit of OBOR/BRI? What is the hidden verse etched into the fabric of this project? Is it:

“One belt! One road! Let’s get together and feel all right!”?

Or is it:

“One belt to rule them all, one road to find them…“?

This will be revealed in coming years when the project is tested in the heat of the real world.

[1] I can’t believe I need to cite a reference here, dear reader? Surely everyone has read or seen this by now?

[2] I’m not naïve enough to believe that the Marshall Plan was an exercise of pure altruism: there were strings attached — principally the injunction that recipients should not become communist and that they should assist the US in containing Soviet Russia. But I am naïve enough to believe that those strings were benign and should have been freely accepted with or without a commitment of aid.