A sideways look at economics

Not that long ago, as I was doomscrolling through X (or Twitter as some still call it), I came across a post claiming that driving was ‘heavily subsidised’ to the tune of £1400–£3000 per driver per year. Wait? What? That’s huge! Can those numbers be correct? I decided to investigate…

I started in the most obvious place — Google (other search providers are available). The brief summary at the top of the search results (thanks be to AI) said: “Yes, driving in the UK is subsidised by taxpayers. The cost of driving is greater than the amount of money the government receives from taxes on fuel, VAT, and vehicle excise duty.”

Case closed.

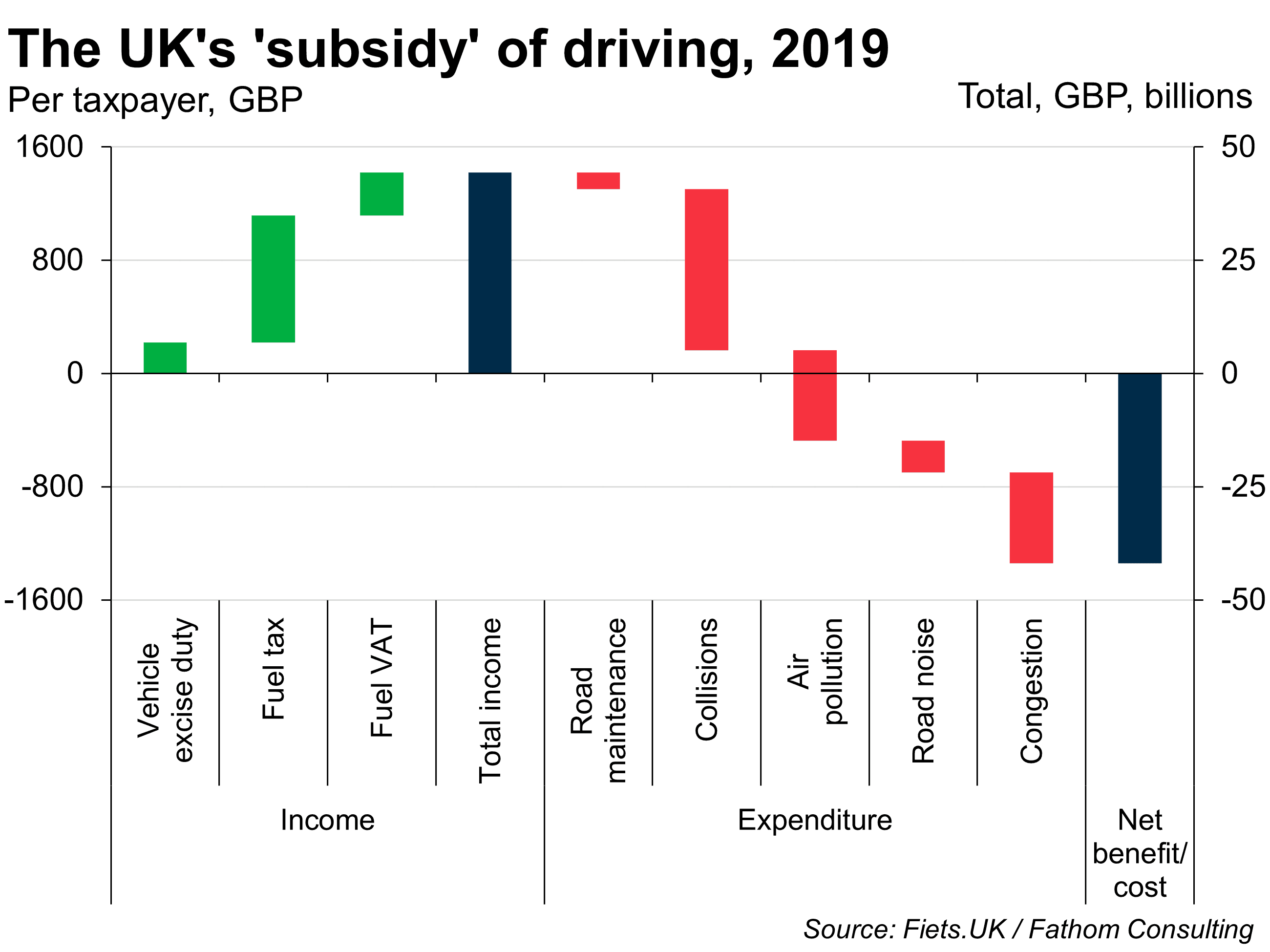

Actually… Me being me, I’d quite like to know how this conclusion is reached. So I clicked on the first recommended link. It presented me with the data summarised in the chart below. As you can see, it shows that the £40 billion revenue (around £1500 per taxpayer) that the government extracts from fuel VAT, fuel tax and vehicle excise duty does not exceed the externalities that arise from driving. Case even more closed. The only catch? This isn’t good economics…

I really have four main problems with the chart above:

- Measuring noise and air pollution: this is the go-to example of an externality, and so is rightly considered. However, it seems at best disingenuous to attribute the costs of both factors entirely to cars. Indeed, driving is just one of many sources of pollution. Another study by Dresden University concluded that cars were responsible for a total of £3 billion in air pollution — less than 20% of the number in the chart above. Note here too that the European Environmental Agency estimates that transport only represents around 25% of total emissions.

- Congestion: Coming in at £20 billion, this is another sizeable externality reported by the study. However, how much of an externality is it really? I don’t deny that congestion is a deadweight loss to the economy but surely it’s one borne mostly by the drivers themselves (and, to a lesser extent, those using road-based public transport). Moreover, if we assume that drivers are rational and choose the optimal journey to work (typically, the quickest), then it seems like, even accounting for congestion, those driving aren’t losing out. Further still, if that £20 billion number is correct then it makes a strong case for more (not less) investment in public road infrastructure (show me any other investment that will deliver 1% higher output per year).

- No positives for the non-drivers: ignoring the revenues that accrue from parking tickets, congestion charges and road tolls is an obvious miss here (in truth I have no idea how large these are — but, if set optimally, they should be charged at a rate that offsets any external costs of the congestion mentioned above). But, more importantly, driving is not done exclusively for private purposes. How many of us ordered something online in the Black Friday sales last week? How many of us have used a bus recently? Hitched a lift from a friend? Even if we don’t drive ourselves, we still benefit from those who do. There are few, if any, who can credibly claim that they derive no benefit from any of this. There must be a reason why every country on earth has cars, vans and lorries, after all.

- Choice of denominator: The figures presented on the left-hand side of the chart use the total number of UK taxpayers in order to gauge the cost per person. Why would you do that? Are they the only ones who suffer from pollution? Clearly not.

Making adjustments in line with points 1, 2 and 4 above would reduce the value of the estimated driving subsidy to around £100 per person per year. That sounds more reasonable, and suggests that excise duties are roughly doing the job they’re meant to do — i.e., taxing away most of an externality. Even so, I wouldn’t consider this to be a proper analysis of the social costs and benefits that arise from driving — to do that would be more work than a simple weekly blog could justify. And that wasn’t the point. Rather, what I’m trying to achieve is simply to debunk some bad economics.

For the record, I’m very in favour of expanding public transport options and investing in cycling infrastructure, in order to make bike commutes more accessible. But, if you want to make the economic case for these things, then it should be done properly — my colleague Felix made a strong argument for cycling in a recent blog. However, if you don’t do that (i.e., if you try to justify your argument on the basis of dodgy economics), then you’ll only discredit your case and even harm it in the long run.

More by this author

An economist’s guide to the Super League