A sideways look at economics

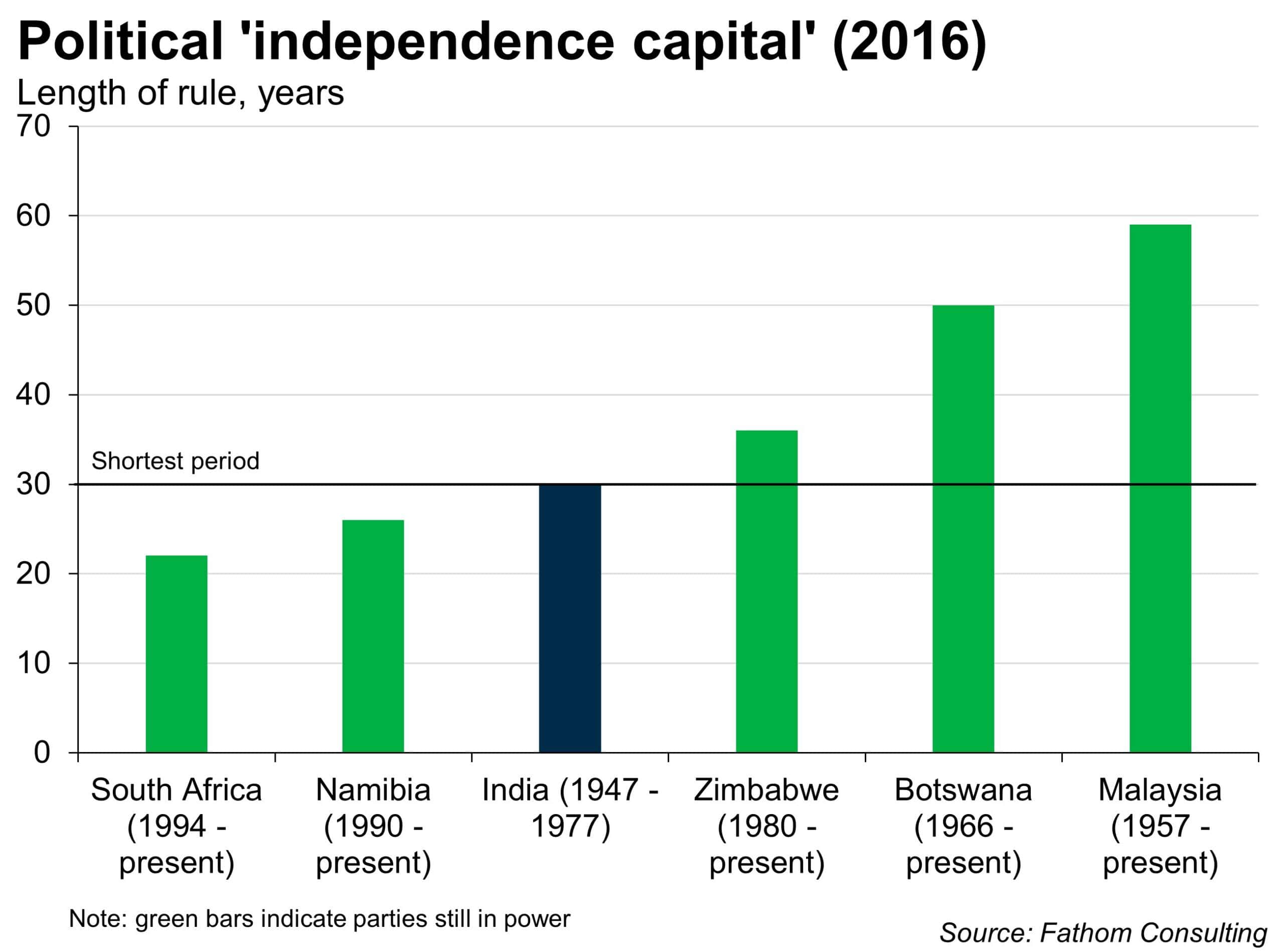

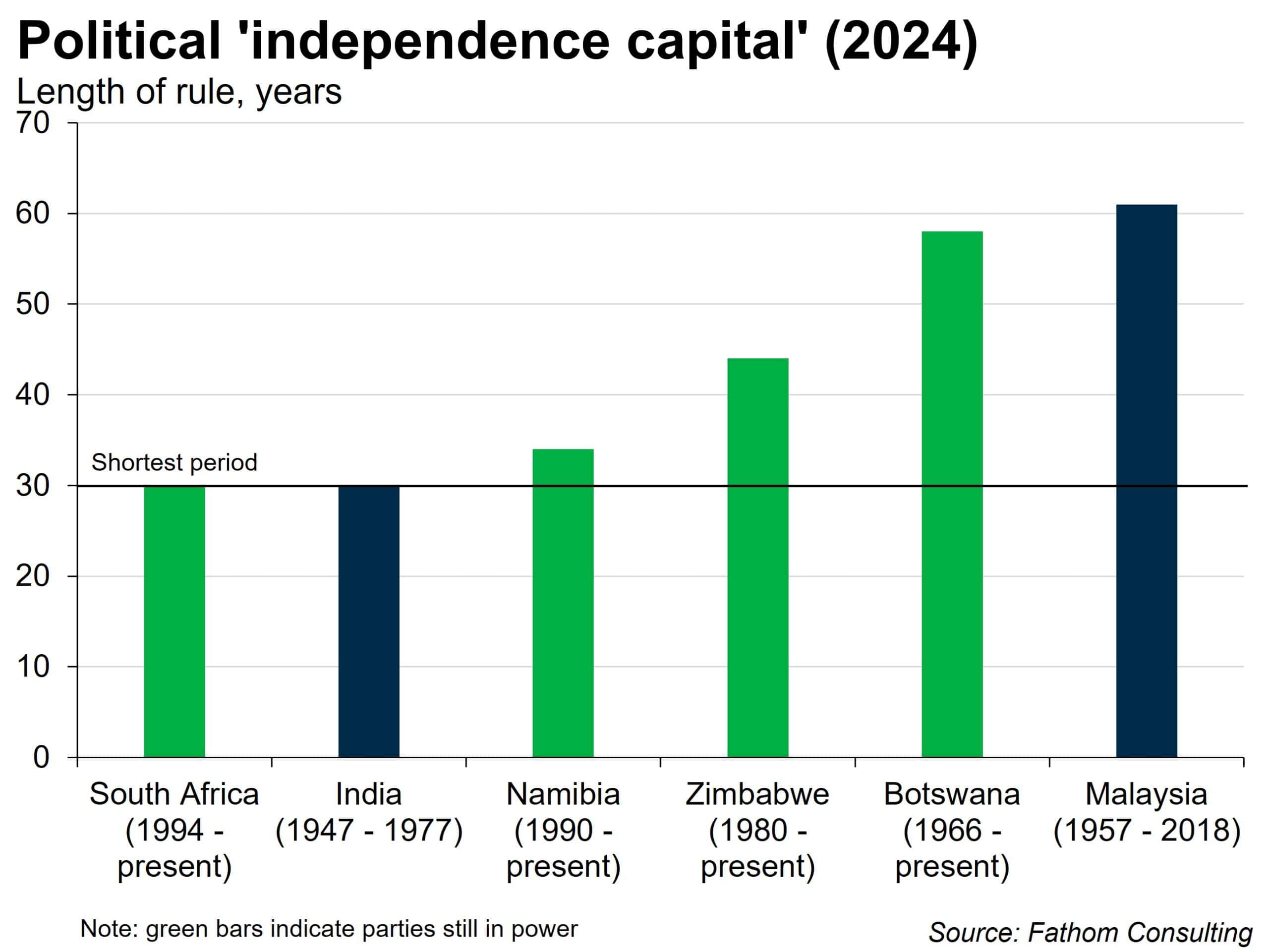

Back in 2016, my inaugural Thank Fathom It’s Friday covered an upcoming election. In a year of shock results, the piece focused on countries where political results were set in stone. Using South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) as an example, it looked at the enduring political success of parties that led their country to independence. At that point, the ANC had been in power for 22 years. Looking at the experience of other ‘freedom’ parties, I reckoned they had at least another eight years of political capital left. This week’s election marks the thirtieth anniversary of ANC rule, with results at the moment indicating they will receive less than half of the votes for the first time on record. They’re not the only ‘freedom’ party that has had to deal with falling favour.

The blog identified six parties that led their countries to independence and then ruled democratically immediately afterwards (many switched colonial rule for single party rule). The shortest such example was India’s Indian National Congress (INC), which ruled for thirty years, from 1947 to 1977. At the other end of the table was Malaysia, with its United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). At the time, they had been in power for 59 straight years. However, their fortunes were to soon change. In 2018, the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition came out on top. However, without the tailwind of independence, their period of political rule was almost immediately challenged, with the subsequent election ushering in a hung parliament.

For the three other countries identified, independence parties continue to rule the roost — albeit with different levels of success. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) is now the longest serving, having ruled without interruption since 1966. However, their share of the vote in the National Assembly elections has been on a downward trajectory, from 80.4% in 1965 to 52.8% in 2019. Something similar is true in Namibia and Zimbabwe. For both countries, the recent presidential election results have been close and a change in power seems probable, eventually. However, predicting the precise timing is difficult. To paraphrase Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan CEO, we will likely be around longer than their rule[1].

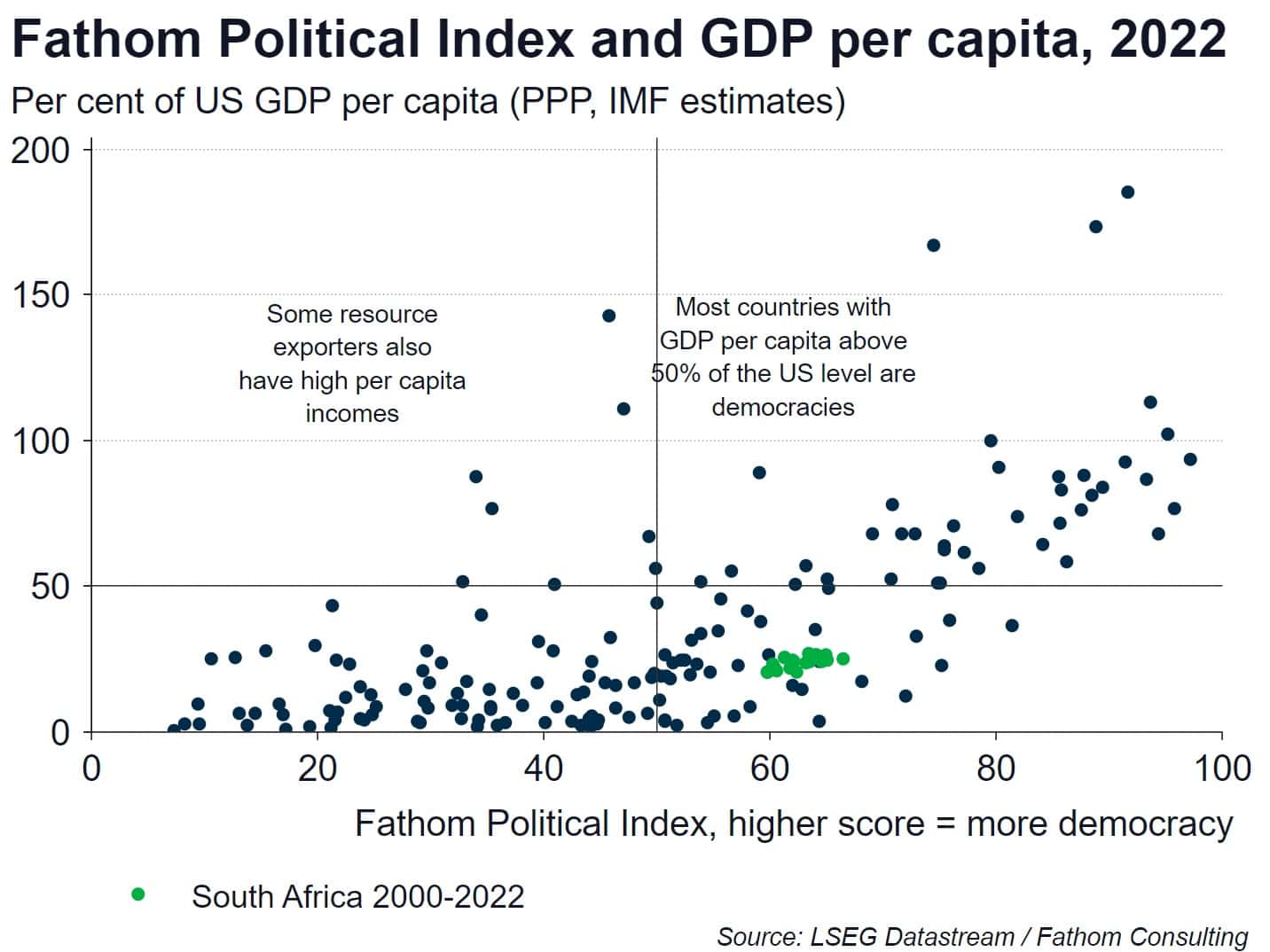

What about the economic consequences of independence parties? It’s not hard to think of potential downsides. Like with goods and services, competition in politics should, all things considered, improve the offer. As the chart below shows, the world’s richest countries are largely made up of multi-party democracies. But, not all rich countries are multi-party democracies. For example, Singapore has been able to transform its economy from one of the poorest to one of the richest, with relatively low levels of democracy. However, there’s no example of a large country, without natural resources, being able to pull off the same feat.

Back in 2016, I flagged South Africa’s deteriorating economic performance. Since then, the picture has not changed radically. The five-year growth rate in GDP per capita (PPP) eased from a peak of 6.4% in 2007 to a pre-COVID low of 0.9% in 2019. However, its recovery from the pandemic has at least been strong, with that figure rising to 2.7% in 2023. Nonetheless, the country continues to suffer from high levels of inequality, unemployment and public debt. There is a long list of revolutionaries, including Nelson Mandela, who have stated their preference for death over a life without freedom. And a period of subpar economic performance seems inconsequential compared to the ills of apartheid. Nevertheless, the two need not be in conflict. Here’s hoping the next thirty years bring both freedom and improved living standards for the people of South Africa. As an Irishman, I won’t complain if their rugby World Cup tally stays where it is.

[1] In response to a question about doing business in China, the JP Morgan CEO said: “I made a joke the other day that the Communist Party is celebrating its 100th year — so is JPMorgan. I’d make a bet that we last longer.”