A sideways look at economics

In between Christmas and New Year, when my thoughts turn to future holidays, I like to open a weather app and marvel at the fact that the temperature is warmer where I live in London than it is on my favourite surfing beach in Devon. It seems wrong that the West Country, imaginatively linked in my mind with sunshine and warmth, should be colder than grey, windy, rainy London — but it is; and not just in winter, but all year round. The reason for this disparity is not to do with climate change (though I will come to that in a bit) but is due to the urban heat island effect. We cover the earth with brick, stone, concrete, terracotta and tarmac, and these thermally efficient materials return the favour by soaking up radiation and slowly releasing it: in the process, gently cooking us.

A couple of extra degrees of heat in a built-up area may not sound like much, but it does have a noticeable effect on the surrounding environment. Rainfall is heavier in the areas downwind of cities, partly due to the rain shadow cast by higher urban temperatures. Water quality is reduced, as warmer waters flow into surrounding streams, putting stress on their ecosystems. Within cities, air quality is poorer, as the higher temperatures increase the production of ozone and other pollutants.

If you live in a city and want to see the urban heat island effect visibly in action, probably the simplest thing to do is to look at the trees. Heat stresses trees: it slows photosynthesis and respiration, stunts growth, reduces fruiting, causes premature leaf drop and turns small ailments into bigger problems. In September I walked down to my local park to collect conkers, but the long avenue of horse chestnut trees had barely produced a single nut. What’s more, their leaves had already started to yellow and fall, many of them mottled with ugly brown markings. The trees had fallen victim to a relatively common (and luckily fairly harmless) tree disease, because the higher temperatures they were enduring had stressed them and reduced their immunity. Some expensive newly planted trees up the hill had died altogether — the growing conditions were too hostile for them to establish themselves.

I said I would get around to climate change; and of course the additional heat retained in the urban environment is coming on top of the already disruptive effects of climate change. The seasonal life cycle of many species of plant depends on the bio-signals triggered by precise changes of temperature. The signalling system becomes faulty when temperatures do not conform to seasonal averages. We have all got so used to it that few people bat an eyelid now when roses linger until December or daffodils are reported in bloom on Christmas Day.

The insidious effect of this however is that native plants that were once completely happy growing in urban gardens are starting to fail to thrive. Heat is not the only issue. Climate change has also brought with it longer periods without rainfall, causing parched growing conditions that disagree with plants that prefer humidity and gentle rain. We are now more prone to extremes of rainfall, from drought conditions that lower the water table and put further stress on trees, to heavy downpours that can destabilise roots and cause landslips.

Few organisations are more aware of this than the National Trust, custodian of hundreds of nationally important gardens — many of them in or very close to cities — whose trees and plantings have a cultural and historic significance. What to do, when the landmark avenue of chestnuts is failing to perform, or when the thirstily drinking silver birches have drained the scant water from the surrounding soil and every other plant around them is dying? Irrigating gardens of that size is not a long-term option. You can mitigate the growing conditions by manuring the soil so that it can hold more water, but such expedients only go so far. Mulching (covering up exposed earth so less moisture is lost to evaporation) could also be useful, but is a vexed issue as it is not a historically authentic practice; and there is an unspoken obligation on the Trust to keep famous landscapes like the cherry garden at Ham House, near Richmond in South West London, looking exactly as they used at an imagined golden era in their past.

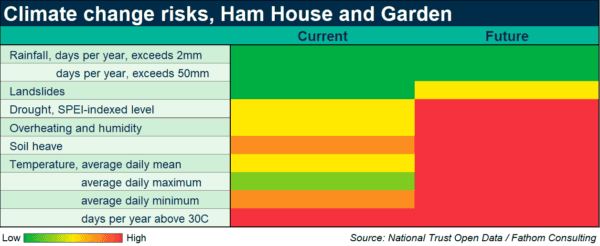

The Trust has been monitoring the situation for the past 20 years through a series of reports that make fascinating reading for a gardener. It has also developed a groundbreaking interactive map of the UK that tracks the developing climate risks. It is worth a look, to check what might happen to your garden.. I looked up Ham House, where I used to volunteer in the garden (the Trust runs on unpaid labour), and found that while heavy downpours are less of a problem than in coastal areas of the UK, rainfall is low — it is in the lowest UK bracket for days of light rain — and drought and heat are becoming massive issues. This has cost and organisational implications for the times visitors want to visit, safe working conditions for staff, maintenance and replacement of plants, and the pressing need for water.

The Trust is sometimes accused of wanting to fossilise the past, but fossilising landscapes exactly as they used to be is not an option. Changes to the climate have already occurred, and more change is locked in — the key issue now for all gardeners, whether domestic or at huge national institutions, is adaptation to the new reality. Human efforts at climate mitigation, by the transition to net zero, will come too late to preserve nature as it used to be. For those of us who live in cities, this might mean planting a deep-rooted, drought-tolerant tree for shade, choosing species of plant with hairy or silver leaves to reflect the sun, installing a pond to create a cooler, more humid microclimate, replacing the conservatory with a shady veranda, or putting a green roof on the garage. On a larger scale, we need more trees in cities, as trees and green spaces moderate the ambient temperature, offer shade and improve air quality by absorbing pollutants and emitting oxygen.

Of course, it’s not just the natural environment that is hit by the social, cultural and economic costs of increasing heat. When you consider how many of us now live in cities, this is an issue that ought perhaps to be higher up the political agenda. Cities occupy only about 0.5% of the land surface of the Earth but are home to more than 50% of the world’s population, who are being exposed with increasing frequency to excessive temperatures, particularly at night, and to poor air quality. It is possible to build homes and offices that don’t massively overheat, but we don’t do it. It’s about time that UK builders were given mandatory rules to insulate against the effects of the temperature extremes that cause thousands of unnecessary deaths. Happy New Year.

More from TFiF