A sideways look at economics

Ever thought about going veggie, or giving Veganuary a shot? Or simply tried to cut out meat and dairy from your diet? Well, you might be interested (or appalled, if you answered no to all of these!) to know that the UK Climate Change Committee is banking on Brits eating 35% less meat and dairy by 2050 in order to help the country reach its net zero carbon emissions target. Is it realistic to expect the nation that brought us the Sunday roast, Cheddar cheese and the full English breakfast to cut out our favourite foods? And why do we need to change our diet in the first place?

Annually, the global food supply chain creates an estimated 13.7 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas emissions – that’s approximately one quarter of all global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions each year. As part of the UK’s response to the ongoing climate emergency, the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) recognises that to reduce economy-wide emissions the country will need to clean up its act across all aspects of life – and this will most definitely include reducing the amount of carbon emissions associated with what we eat.

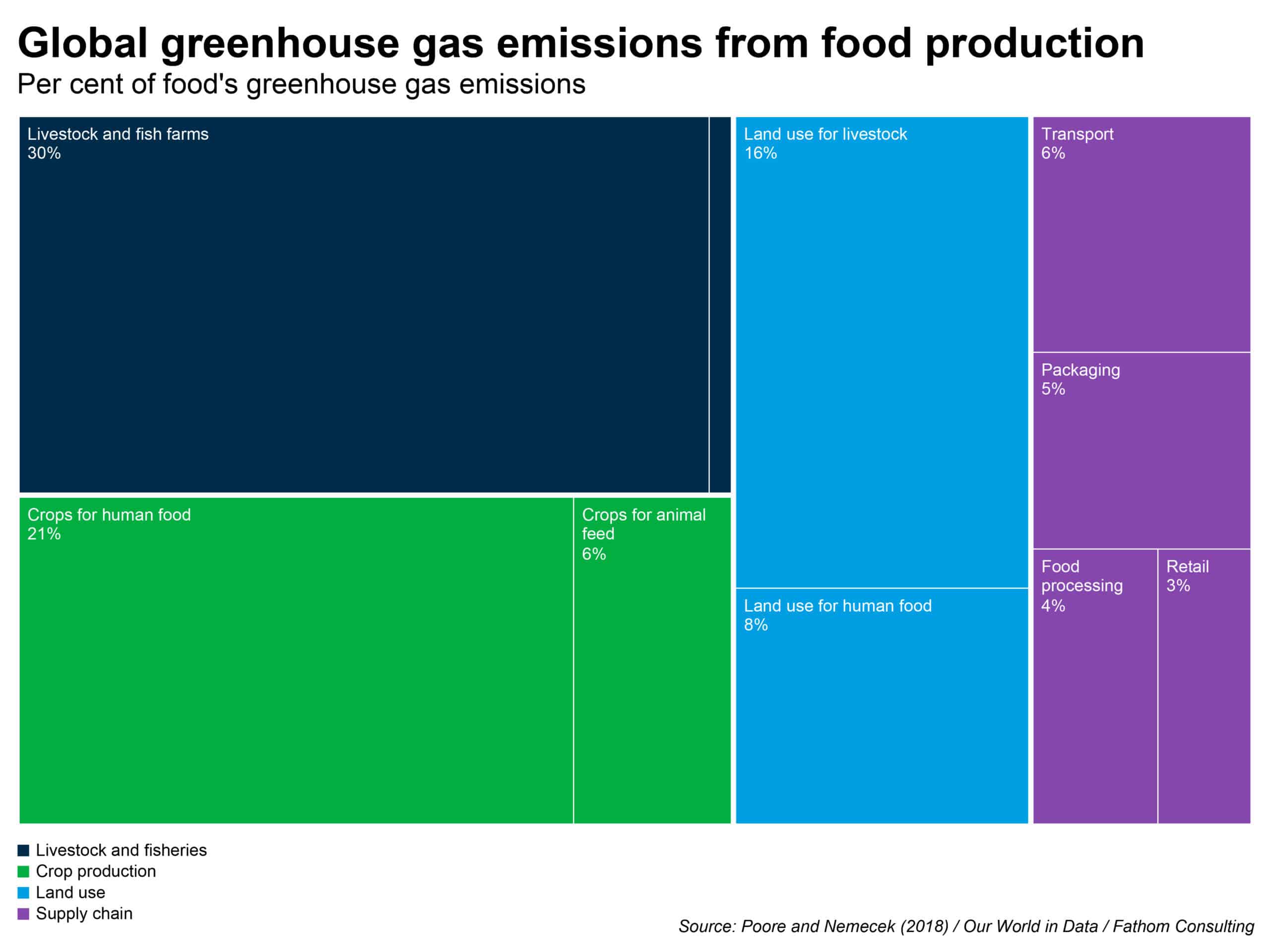

The most comprehensive study on emissions within the food supply chain, a 2018 paper by Poore and Nemecek which analysed data from 38,000 commercial farms in 119 countries, found that most GHG emissions within the food supply chain originated from farming practices or the land change (eg deforestation) associated with production, rather than from transport, packing or retailing of produce. Food production emissions largely consist of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane gases, which result from agricultural practices. You may have thought that eating locally-sourced produce or buying seasonally available foods from the farmers’ market would have a beneficial impact on emissions (and these actions will help to some extent); the truth is however that the biggest impression we can make on food’s GHG emissions is to change what we eat — and, in particular, to reduce our consumption of meat and dairy products.

When scrutinising the data in more detail the authors estimated that almost 15% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions could be directly linked to meat and dairy production. Livestock farms, land use associated with livestock, and the crops required for feeding animals, contribute the most to emissions within the supply chain.

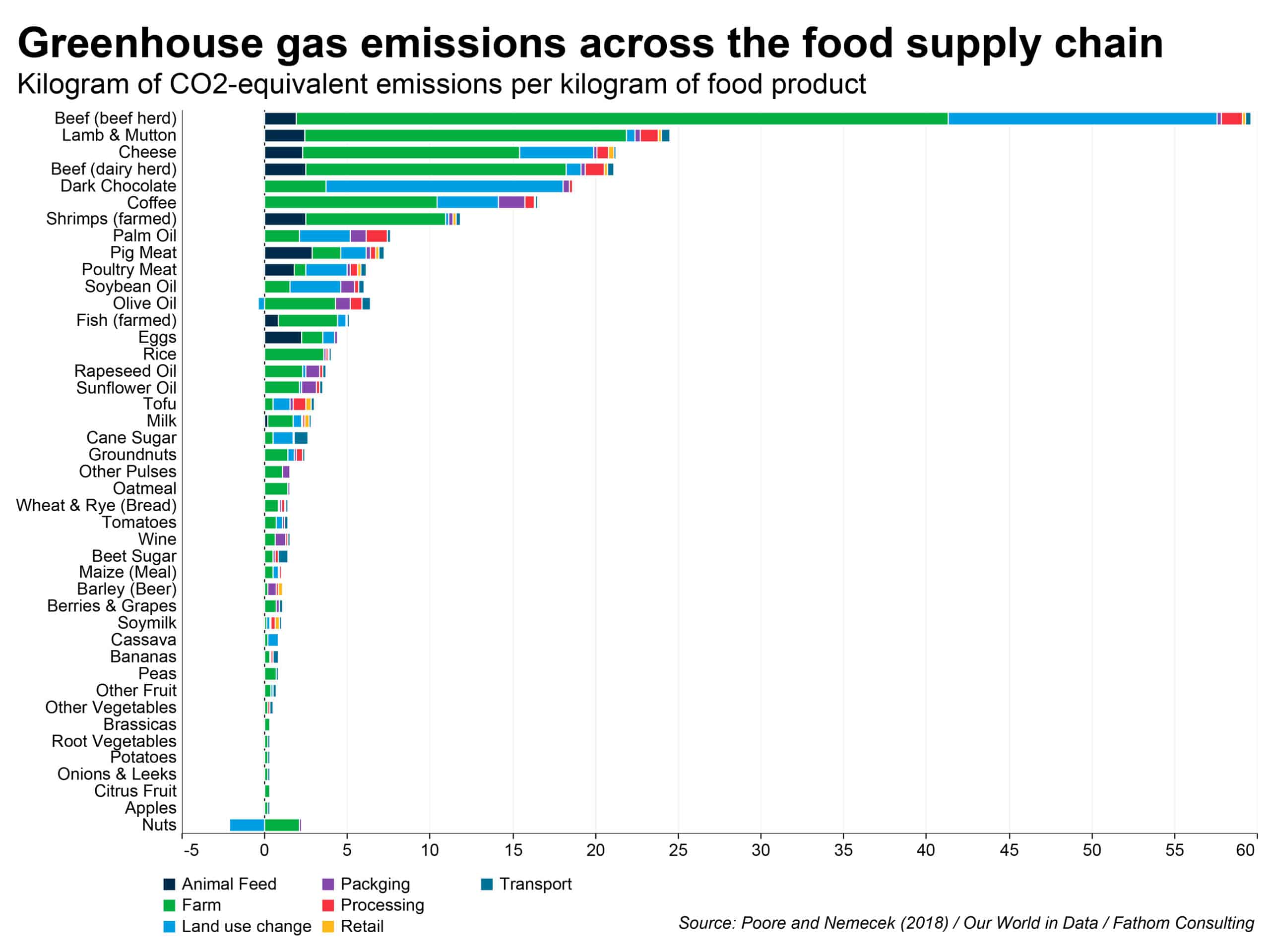

Considering specific food products, the authors identified red meats, dairy, and other meats (as well as some of Fathom Towers’ favourite treats, coffee and chocolate) as the serial (or should I say ‘cereal’?) offenders. They find that typically one kilogram of beef produces 60 kilograms of CO2-equivalent emissions. Just let that sink in… that’s thirteen and a half kilos of emissions bundled up with your typical 8oz/225g steak (maybe try visualising bicep curling that the next time you sit down for a Friday night steak dinner?). Other meats are also emission-intensive, with one kilogram of lamb or mutton creating 25kg of emissions, pig meat 7kg, and poultry 6kg, in their production. And for the cheeselovers out there, there are 21kg of emissions associated with your 1kg pack of farmhouse mature cheddar[1].

Typically, plant-based foods offer a more environmentally friendly alternative. Swapping out some, or all, meat and dairy from our diet can be achieved without compromising our dietary needs.

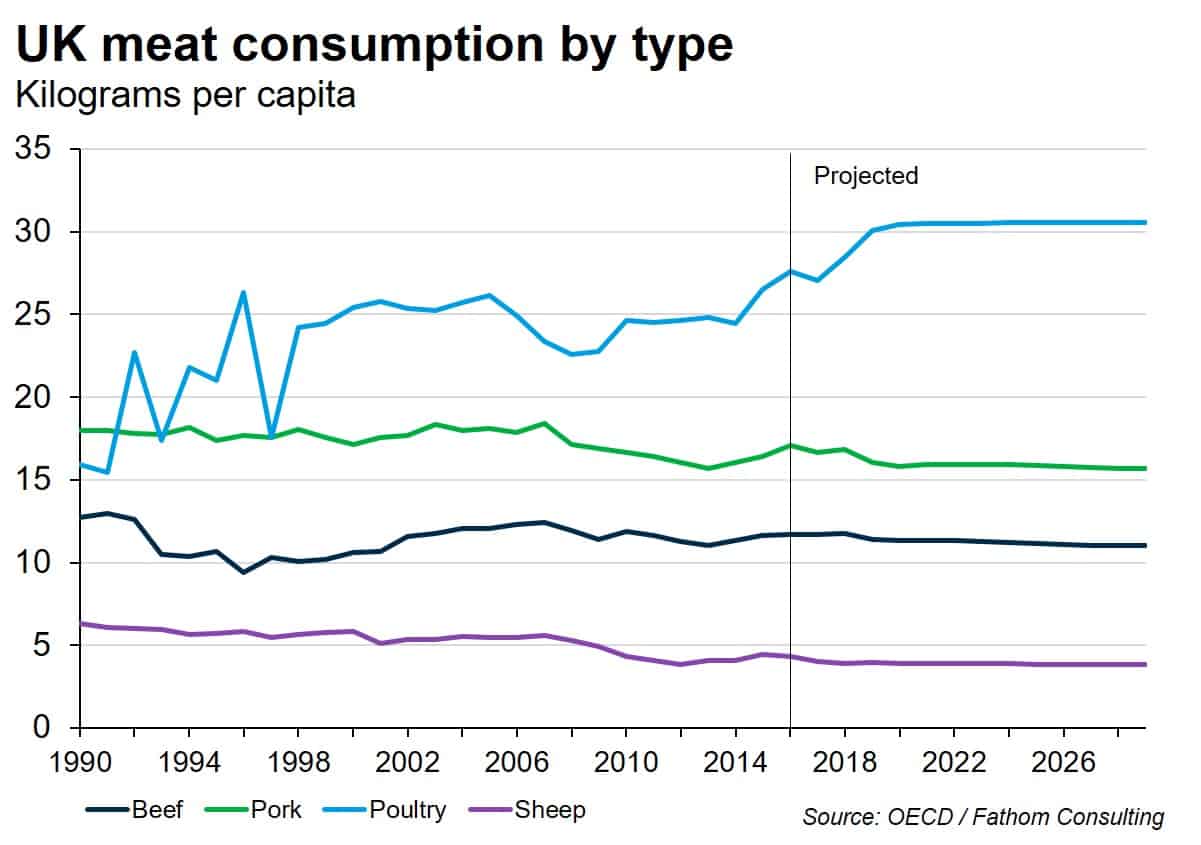

In what might seem like a radical change to our diets, the CCC anticipates us all eating 35% less meat and dairy by 2050 in its ‘balanced pathway’ scenario. Unsurprisingly there will be some ‘replacement’ of emissions, as we transition from meat and dairy farms to cultivating alternative, plant-based proteins; however, the overall impact should bring down total emissions within the food supply chain.

The hope is that reducing our dependence on meat (particularly red meat) and dairy for calories will allow us to reduce the negative impacts of emissions within the supply chain, and free up land use for other green-initiative projects such as afforestation[2] — which should in turn prevent the loss of biodiversity.

At an academic level we can all appreciate the strong case for reducing meat and dairy consumption to help us reach net zero (cue eye-roll from meat-lovers), but given human nature and economics, how likely is this to be achieved?

For most meat-eaters, emissions do not feature in deciding which meat to eat – we largely consider our private costs and benefits, as economic theory dictates. Similarly, farmers and meat producers respond to market demand. However, the production of meat negatively impacts the environment. This damage, which is not accounted for in farmers’ costs nor in the subsequent food chain, is known in economics as a production externality: a type of market failure. Although these costs are not considered by producers, they will be inflicted on future generations in the form of higher sea levels, land degradation, poorer air quality and more extreme weather events, with all the human and natural disasters these entail.

Theory suggests that negative externalities can be ‘internalised’ through taxation: e.g., a carbon tax on meat, such that the price increases and demand falls to a socially optimal level. Determining that level of tax is not easy, however, and a tax on foodstuffs is seen as highly regressive. Agriculture is currently subsidised in the UK (meat is sold with 0% VAT) and taxation is not the path the UK government plans on taking, for now at least. If political appetite changes in future, we may see a meat ‘sin’ tax, or more stringent production standards (such as free-range only), which will likely result in higher prices and help to bear down on consumption, but for the moment they are not on the agenda. Action is being left to the individual.

In the absence of a price hike, if you are a meat-lover and a rational utility maximiser, why would you cut your meat consumption? Altruism may impel people to make sacrifices to benefit others without expecting tangible reward, possibly due to the emotional reward of feeling good about themselves: a ‘warm glow’. Surely, this is what giving up meat for the environment would require, like giving to charity, donating blood, or volunteering? However, according to blood.co.uk, 81% of people aged 18-24 years have never given blood, even though we know it is not harmful and can save lives. Likewise, only 65% of the British public gave money to charity directly or sponsored a friend/family member in 2016. This suggests that although altruism exists, the evidence is less convincing that we are willing to make ourselves worse off to make others better off: i.e., to forego the immediate pleasure of a steak in favour of the welfare of future generations. Individual responses to the climate change message over the past ten years tend to confirm this.

Over half of adults in both the US and UK say they want to reduce their meat consumption, but data would suggest that meat consumption is not falling at a rate anywhere near that required to reach net zero by 2050 – so why the discrepancy? Perhaps the vastness of the climate crisis encourages this kind of performative activism: doing something (or saying you are doing something) for the benefit of another because it benefits oneself, usually in the form of social clout or improved reputation. This is a criticism that many ‘militant vegans’ have had to face, as jokes such as “How do you know if someone is a vegan? Don’t worry, they’ll tell you” circulate the internet. Could the wish to appear socially responsible incentivise a shy meat-lover to lie about their consumption? Are they telling themselves they want to reduce their meat consumption to appease their own conscience, without following through – because who is checking? If so, this is a result which will have no beneficial impact on the environment.

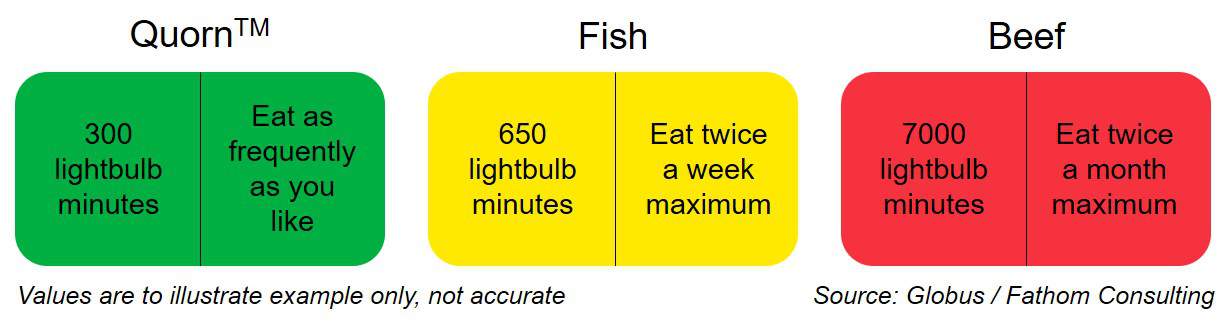

So, a tax seems politically unlikely at this stage and altruistic vegetarianism also seems far-fetched as a solution to the world’s climate problems. But there may be a middle ground. The path to net zero requires human behaviour change across many aspects of life: less air travel, replacing your home heating system, purchasing an electric car, as well as changing your diet. What if we treat this transactionally, like many things in life that we must forego or give up? Ever thought: I went for a run, so I can have pudding? This is an almost daily occurrence in my life, and likely a similar trade-off in yours too. Who is to say that in future we will not think: I am going flexitarian so I can continue to buy £1 bikinis from Missguided? The net result will not have the desired effect on emissions, but might still be better than nothing — so long as consumers have the necessary information. If we continue to be unaware of the emissions associated with our consumption decisions, however, then this approach could do more harm than good. For example, if we did not know the calorie content of food, we might think a gentle 20 minutes on the treadmill equates to a Big Mac — something that is, unfortunately, not true.

To achieve the CCC’s goal of 35% reduction in meat and dairy consumption by 2050, the government will likely implement nudge policies. De Bakker (2012) argues for a reframing of the ‘meat and two veg’ norm for a meal, so that in future meatless meals are considered ‘normal’. Overcoming this common framing bias, of a meal without meat not being a ‘proper meal’, is a basic requirement if we are to meet the CCC’s target. This could be facilitated by policies to include more vegetarian and vegan options on menus, especially in schools; and potentially too to require food labelling to include information regarding the environmental impact of foodstuffs – something which the market has so far failed to provide.

Persuading humans to change their meat consumption is no easy feat, so maybe our answer comes from somewhere else: technology. Although, in my opinion, they still have a long way to go before their quality allows them to fully substitute meat, plant-based meat alternatives (lab-designed food that mimics meat in smell, taste, and texture, but which actually comes from alternative proteins) have seen rapid growth, with Tesco planning to retail a fake meat version of every meat product they sell within four years. Recent studies have predicted this is what will cause meat consumption to reach its peak by 2025 in Europe and US and then start to decline, so all I can say is, watch this space….

[1] It’s important to note that the authors’ calculations consider a wide range of farms (from small-hold to commercial) and many different farming methods (manual to automated), across many different climates. All of these factors will help determine the emissions associated with a product. The figures stated here are averages taken from the authors’ multi-factor database.

[2] By 2035, the UK CCC expect 460,000 hectares of new mixed woodland to be planted to remove CO2 and deliver wider environmental benefits. 260,000 hectares of farmland shifts to produce energy crops. Woodland to rise from 13% of UK land today to 15% by 2035 and 18% by 2050. Peatlands to be widely restored and managed sustainably.