A sideways look at economics

As a tired father of two I thought it might be fun to calculate a monetary value that could convince me to try to have a third child (or, more accurately, convince me to attempt to convince my wife to try). The figure: £15,669,144,525.

4 years of nursery: £105,600 (£2200 per month x 48)

18 years of clothes: £27,000 (£1500 per year x 18 – conservative: a pair of Nikes can cost £200!)

Pram: £1,159 (Stokke Xplory X pushchair)

Bigger car: £300,083,000 (Tesla Cybertruck – kids care about the environment so needs to be electric. Costs £63,000 in the US, but not currently available in the UK so figure includes estimated £300 million to lobby UK government to approve, plus shipping costs of £20,000)

Extend garage: £150,000 (Cybertruck won’t fit in our garage so assumes we purchase of neighbour’s garage and merge with ours – I haven’t discussed this with them yet)

Flights for grandparents: £250,506 (three business class return tickets for each grandparent, three times per year, for 18 years)

Accommodation for grandparents: £4,687,200 (our flat will be a bit crowded with three kids so put grandparents up at the Ritz, one month at a time, three times a year, for 18 years – note: hotel needs to be a nice one to convince them to return each year!)

Transport from Ritz to home: £5,670 (£1.75 bus fare from Ritz to home and back for 30 days, three times a year for 18 years – use the bus, save money)

Private school (Eton or similar): £550,000 (£50,000 per year for eleven years)

Private school for existing kids: £1,100,000 (don’t want them to feel left out)

Harvard Law School: £362,680 ($116,000 a year for four years, which includes accommodation costs)

University for existing kids: £725,360 (no being left out)

Maths tutor: £50 million (cost of luring latest Fields Medal winner away from hedge fund job)

Fencing lessons: £335 million (with the Rock – £67 million annual salary x 5)

Driving instructor and chauffeur: £720 million (Lewis Hamilton’s new deal at Ferrari is worth £40 million per year x 18)

Football coaching: £810 million (by David Beckham – I like him; according to Forbes, this is the value of his Inter Miami football club – buy it to ensure availability of his services)

The total comes to £2,223,048,175. But it could be twins or triplets? Multiply by three: £6,669,144,525. This total doesn’t even include the cost of my free time (£1bn but multiply by three as it could be triplets = £3 billion). Or my wife’s free time (£2 billion x 3 = £6 billion). Grand total: £15,669,144,525.

I could leave my analysis there, but economists like to overthink things and make them less fun, which is what happened when I did some digging into fertility rates and reasons for differences across the world.

The decision of whether to bring a child into this world is so personal that we need to recognise that any macro analysis will never perfectly match one’s individual circumstances. But like it or not, the fertility rate (defined as the average number of children born to a woman during her lifetime) has important economic implications: from planning how many doctors and teachers will be needed and how to pay for them, to estimating things like a country’s trend rate of GDP growth.

It also happens that low and declining fertility rates are a source of concern among policymakers in many rich countries, where the rate is often below 2.1, the level needed to keep the size of the population constant. South Korea, for example, which has the world’s second lowest fertility rate at 0.8, has started offering cash to new parents to try to reverse the trend. Hungary, with a fertility rate of 1.6, offers lifetime tax breaks for people that have kids: the more kids you have the bigger your tax break! Throwing cash at the problem ought to help, but countries like Taiwan have already done this with little success.[1] Cash isn’t always king, it turns out.

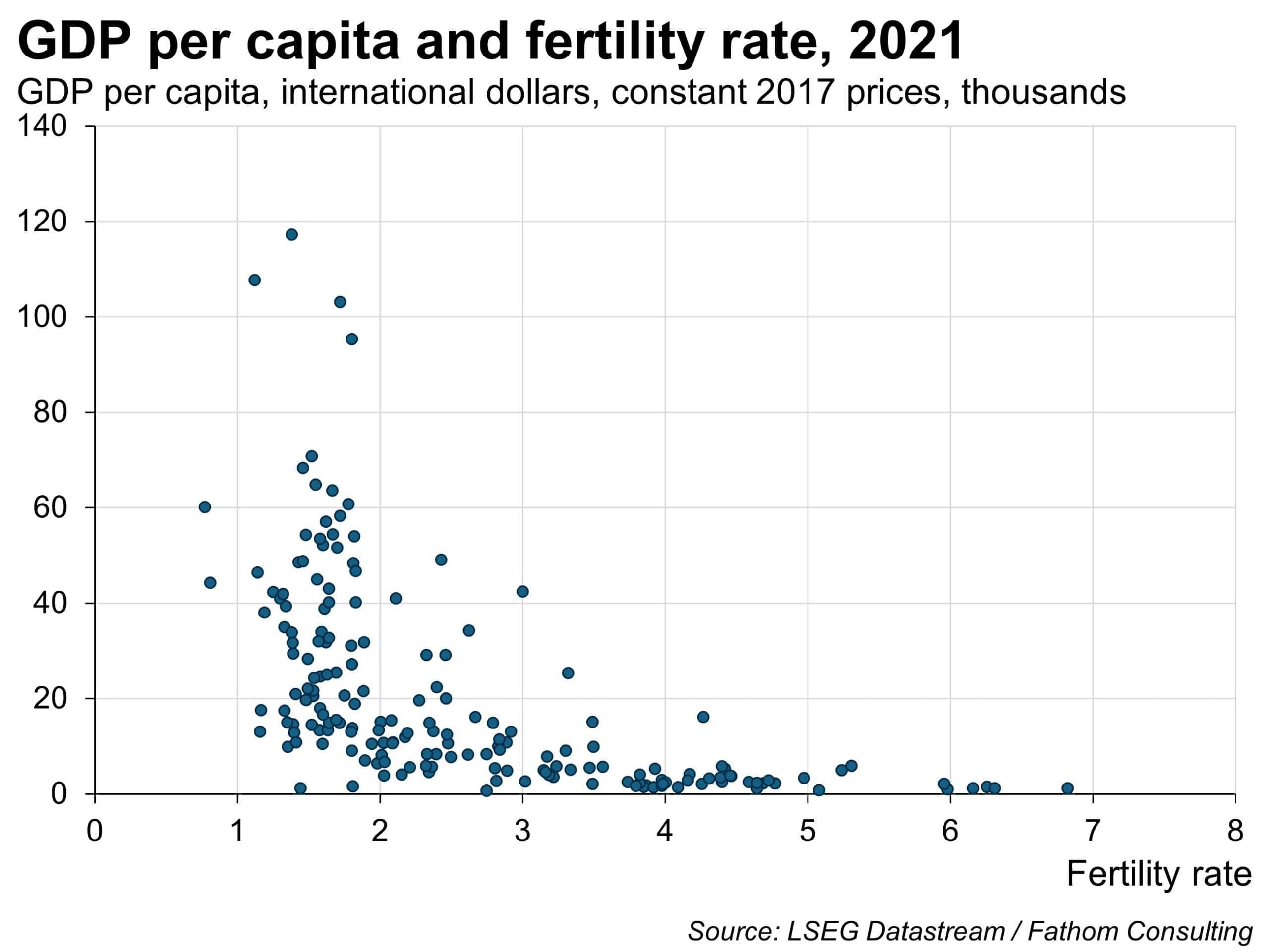

From my own point of view (as a tired dad of two and an economist), a cold way to think about the decision to have another child is the amount of your time this will take, and the value you ascribe to this time. Yes, we love the kids and they give us endless love, joy and happiness, but the hard truth is that the more you value your time, the greater the opportunity cost of having a kid. Perhaps this explains why the fertility rate is lower in richer countries? The more you can earn, the more you value your time and the higher the opportunity cost of foregoing this time to look after the kids. This is a somewhat negative argument, but this hypothesis seems to be supported by the strong negative relationship between GDP per capita and the fertility rate across countries. And in most countries where GDP per capita is above $40,000 per year, the fertility rate is less than 2.1.

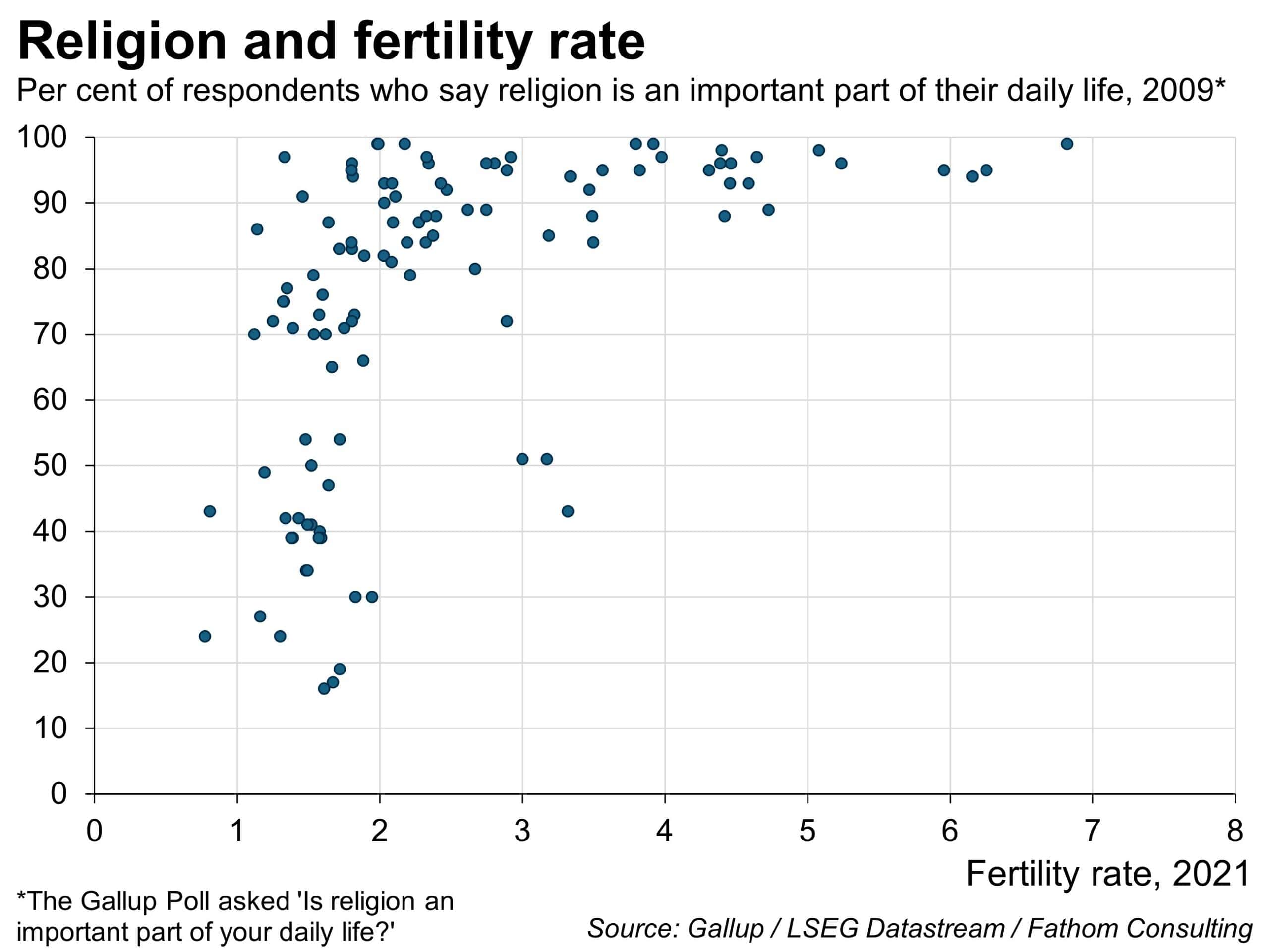

But richer societies ought to be able to afford more childcare, which gives parents back their time. So wouldn’t you expect a positive relationship between fertility rates and GDP per capita? In fact the reverse is true, even if the relationship isn’t linear. Some studies suggest that religious belief positively correlates with fertility.[2] Our own chart suggests this may be the case, although again the relationship isn’t linear.[3]

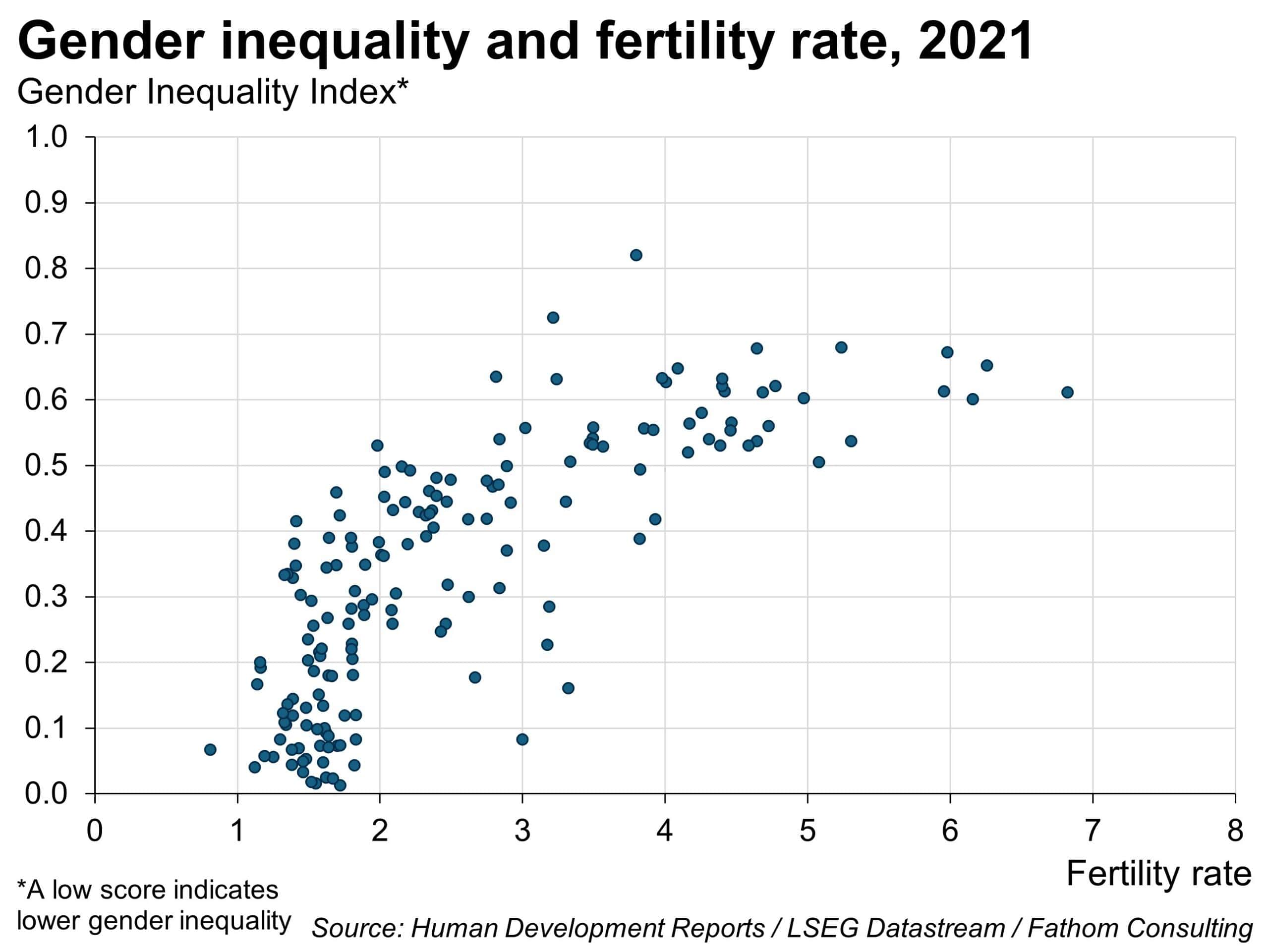

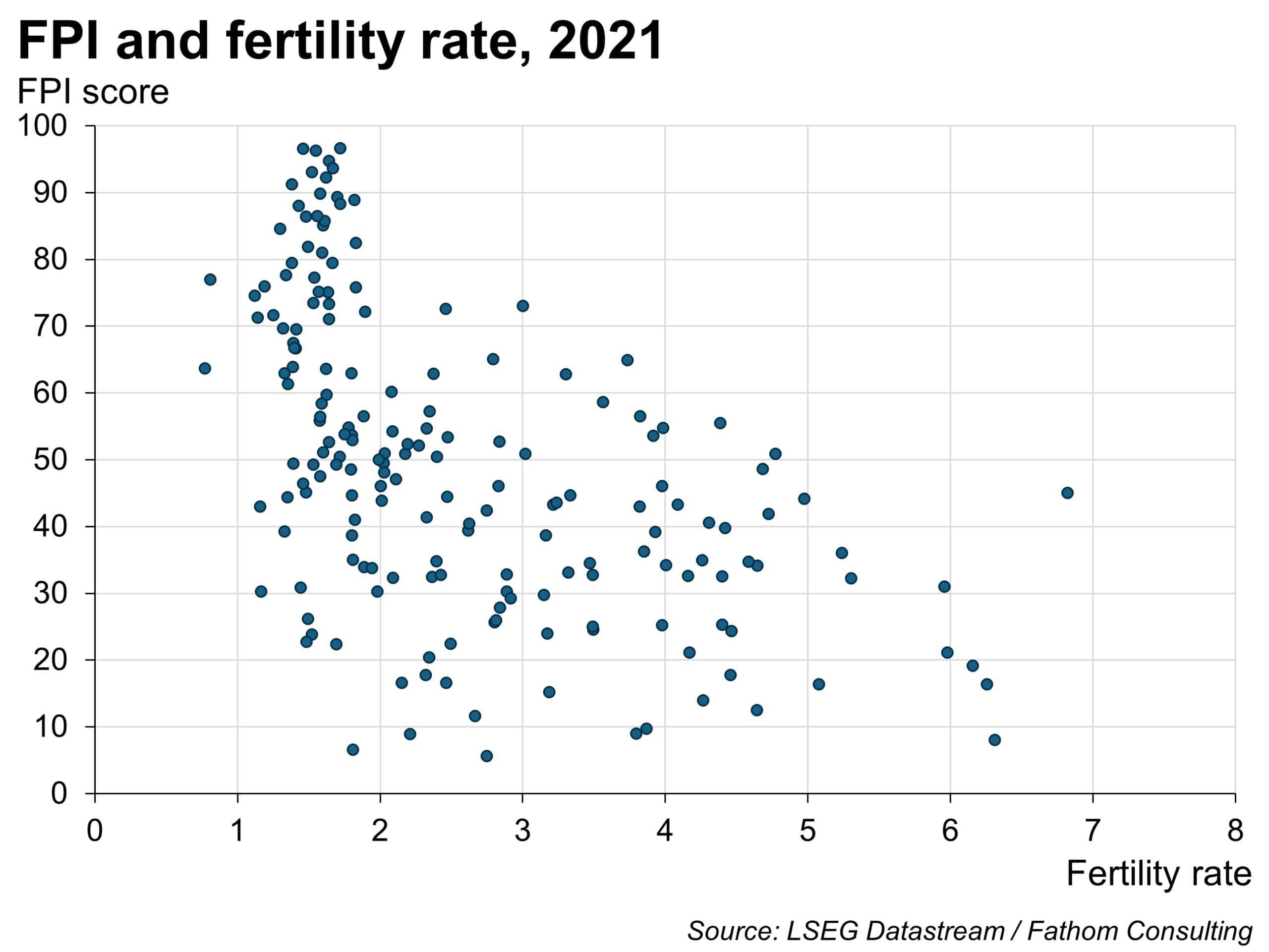

Since women often spend a disproportionately high share of time looking after kids relative to men, it might be useful to consider how much women, specifically, value their time. I’m not sure where to find such data, so I have used the UN’s Gender Inequality index instead (with my hypothesis being that women ought to value their time more in societies in which they have greater opportunities), and thrown Fathom’s measure of democracy and governance (FPI) into the mix for good measure. It turns out that greater gender equality and better governance are consistent with lower fertility, and vice versa.

My attempts to explain the fertility rate econometrically using these four variables (GDP per capita, religiosity, gender inequality and FPI) at first yielded a surprising and uncomfortable result: the strongest and only significant explanatory variable is gender inequality, and the sign is positive, meaning that more gender equality is consistent with lower fertility rates and vice versa.

Why would this be the case? Could it be that women with more career and life opportunities are less likely to want to have kids, or more likely to want to have fewer kids, because they value their time more, or can earn more money with this time? Or since they have better career opportunities that they spend more time at work, have less free time and are therefore less willing to give up this free time to look after kids? Perhaps women in more equal countries fear missing out on career, or life, opportunities if they take a break to have a child. More could be done, I’m sure, to address such concerns, like men doing more childrearing (and spending less time writing TFIF).

But I’m not comfortable with these results. For a start, taking logs of the four explanatory variables revealed that GDP per capita was the only statistically significant explanatory variable. Logging GDP per capita but keeping the other variables unlogged resulted in both GDP per capita and gender inequality being statistically significant, suggesting that both of these factors play a role. More problematically, all four of these variables are closely correlated, especially with GDP per capita, resulting in an econometric problem called multicollinearity. Personally, I suspect that is the main driver and that the econometrics is picking up gender equality because this correlates highly with GDP per capita. More comprehensive modelling work should also probably consider things like life expectancy and the infant mortality rate.

Clearly, this issue deserves a lot of thought and discussion – more than I can give in this blog. The best I can do for today is to explain why it would take nearly £16 billion tempt me to into attempting to convince my wife into having a third child. And even that isn’t very useful as it doesn’t consider the happiness, joy and love that a third child would bring – perhaps that tops £16 billion. At the end of the day money is just money, and while we economists like to put a monetary value on things, occasionally we need to remember that some things are priceless. Like kids. Or free time. Take your pick.

[1] https://www.vox.com/23971366/declining-birth-rate-fertility-babies-children

[2] https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-8331-7

[3] The best measure of religiosity across many countries that we could find was a Gallup poll from 2009, which is somewhat out of date – I assume however, that these views change relatively slowly over time and therefore the finding still stands.

More by this author